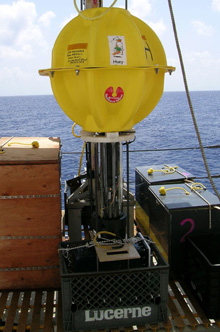

Rotary camera "H," better known as "Huey," on the elevator prior to deployment. Click image for larger view and image credit.

Friendly bets are commonplace during this expedition. Though this image did not capture the specific bet associated with "Louie’s" arrival at the surface, it did memorialize another bet made early in the cruise. Click image for larger view and image credit.

Rotary Time-lapse Cameras: Part 2

June 29, 2007

Ian R. MacDonald

Texas A&M University – Corpus Christi

26° 21.25 N

94° 29.83 W

![]() SeaSnap 360 autonomous rotary time-lapse camera. (Quicktime, 772 Kb.)

SeaSnap 360 autonomous rotary time-lapse camera. (Quicktime, 772 Kb.)

In the June 19 log, I discussed many of the advantages of using time-lapse cameras for science, as well as the challenges associated with building and operating them. In this log, which I've entitled "Part 2," I want to update you on what happened with the new model of camera when we returned two weeks later to the Atwater Valley 340 (AT 340) site to retrieve the camera.

Everything started out quite well! Upon arrival, we discovered that the camera was still in place, right where we had left it. As the Jason remotely operated vehicle (ROV) pulled up close to the camera, I was slightly concerned to see that it had stopped taking pictures. But I breathed a big sigh of relief when I saw that the housing was still intact; the inside seemed dry and secure. Now all we had to do was get the camera safely back to the surface and onboard the NOAA research vessel Ronald H. Brown.

While the Jason rested on the sea floor, I hung a hydrophone over the side of the ship and beamed the release command — a strong acoustic signal — to the camera over 2,000 meters (m) below. This signal starts an electric current over a circuit below the camera housing. There is thin piece of wire on the positive side and grounding contact on the other. In between are six inches of seawater. When the current flows across this six-inch gap, it causes the thin wire to corrode rapidly, eventually burning through the wire and causing a mechanism to drop an anchor.

After "Louis" was released from the bottom, spotters on the bridge and bow of the Ronald H. Brown kept a lookout for the camera system’s bright yellow float. Click image for larger view and image credit.

This 360° image was taken during "Louie’s" first deployment. It provides a representative example of the type of imagery collected with the time-lapse rotary camera. Though faint, you may notice the lights from the Jason ROV (visible on the right hand side). Click image for larger view and image credit.

Soon after recovering the rotary time-lapse camera in one of the Ron Brown’s small boats, Nicole Morris, NOAA Sea Grant Fellow, and Ian MacDonald, Texas A&M – Corpus Christi, begin to disassemble the instrument. Click image for larger view and image credit.

After sending the signal, I raced back to the control van to watch the release on video in the Jason control van. About 15 minutes later, the burn wire failed, the anchor dropped, and the 17-inch Benthos glass sphere began lifting the camera to the surface. Immediately, the bystanders in the van began laying bets as to when it would get to the surface. I helpfully provided information on the system’s weight in water and air and its positive buoyancy. (I failed to mention that I knew from previous experience that it should rise at about 40 m per minute.) So 49 minutes later, when the bridge watch spotted the yellow ball, my bet of 55 minutes won a round of beer when we get back to port in Galveston on July 6.

Better yet, the camera was in great shape and had taken over 1,300 pictures on the bottom. There do seem to be a few areas where I can make improvements. A lens cover I glued in place to cut back on glare had peeled off — partly obscuring the corners of the images. A high spot on a connector had rubbed against the inside of the glass — causing the rotation to stick in a few places. The great news is that the camera recorded several resident fish that seemed to reappear after the ROV had left the site. The images also show numerous small fauna that came and went while the camera was on bottom.

It will take my students and me several months to sort out all the information. For now, I am happy with a proof of concept and a chance to “immerse” myself in the seep environment. Hopefully, I’ll have a few more images to share once we get to Alaminos Canyon in a few days.

Note: The science party extends huge congratulations to Oscar Garcia and his wife, Diana, on the birth of their second child. Oscar was on the first leg of this cruise and made it back home with just a few days to spare before Miquel Angel was born. Congratulations!!