This photomosaic is a careful compilation of multiple images of a mussel bed at the Atwater Valley 340 site. The images were taken with a downward-looking still camera in 2006. Click image for larger view and image credit.

The sea-floor community of tubeworms, mussels, shrimp, and a crab in the Green Canyon 852 (GC 852) site. Click image for larger view and image credit.

Mission Plan

Chuck Fisher

Penn State University

The Expedition to the Deep Slope 2007 mission includes two types of activities, which together will advance our understanding of the sea floor communities that live in association with hydrocarbon seepage and hardgrounds in the deep Gulf of Mexico. We will revisit about half of the sites we discovered in 2006, complete our characterization of these impressive sites, and also collect time series data that will provide important information on how fast seep animals grow and how the deep communities change over time. The second objective will be to explore three to five new areas and to characterize any new sites and communities we discover. We have identified likely sites for these exploratory dives and will use them to fill in key pieces to the puzzle of the seep animal and coral distribution patterns in the deep Gulf of Mexico. All of the sites we will study are in areas where energy companies could soon begin to drill for oil and gas. Our mission will provide essential information on the ecology and biodiversity of these deep-sea communities to regulatory agencies and energy companies as the quest for oil moves into deeper and deeper water.

The largest oil reserves in the continental United States are found in the Gulf of Mexico. The Minerals Management Service (MMS) of the U.S. Department of the Interior oversees the responsible extraction of these natural resources and has been supporting the study of the hydrocarbon seep communities since the early 1980s. Up until a few years ago, these studies were focused on communities found between 500 and 1,000 meter (m) depth.

Meanwhile, energy companies have continued to develop the technology for extraction of oil and gas from deeper and deeper water, and now have the capability to drill oil wells in all water depths in the Gulf of Mexico. This is one of the reasons that the MMS and NOAA have funded our study. It is also one of the reasons that our project received a Cooperative Conservation Award from the Department of the Interior this year for this project.

On June 4, our plan is to depart Fort Lauderdale, Florida, on the NOAA ship Ronald H. Brown, beginning our two-day transit to our first dive site. We will begin our operations at one of the lushest sites we discovered last year, which we call AT 340 — which is short for "Atwater Valley lease area, block 340," the MMS lease block where the site is located. When we first arrive, we will deploy an array of navigational transponders that will allow us to make detailed maps of the sea floor and to always know where we are (within a meter or two). The Jason II remotely operated vehicle (ROV), designed by the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution’s Deep Submergence Laboratory, can work around the clock. As soon as our transponders are ready to go, we will launch the ROV and begin our bottom operations. We do not want to stop the bottom operations just to retrieve collections so we will be using an “elevator” to send our collections back to the surface (without recovering the ROV). On board the ship, teams of scientists will be working on these valuable collections: analyzing the chemistry and geology, identifying the animals, and studying the microbial communities.

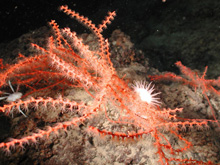

A red gorgonian from the Coral Garden area in GC 852. The eight tiny tentacles on each polyp place this coral in the Octocorallia sub class. You can also see an anemone attached to the coral and a small galatheid crab in the background. Click image for larger view and image credit.

The next site we will visit will be GC 852 (located in the Green Canyon lease area, block 852). In addition to lush communities of tubeworms and mussels, we also discovered a beautiful coral community at this site. We have several studies to complete at GC 852, but when we are finished we will change the types of equipment we have on the ROV and begin the most exploratory phase of the expedition. We will dive on at least three new sites, and perhaps as many as five. What we do and how long we spend working on each site will depend on what we find. These are sites never before seen by human eyes, and we will have to adapt our plans as we go.

About halfway through the expedition we will have an at-sea exchange of personnel. Six new scientists will board a transfer ship in Florida and meet us about 150 miles off the coast of Louisiana. Six other scientists will disembark our research ship, take the “taxi” in to a port in Texas, and fly back to their home laboratories. Meanwhile, the rest of us will continue our exploration and study of the deep seep sites. Our plan is to finish up with the sites offshore of Mississippi and Louisiana by about our third week at sea, and then move 200 miles further to the west and make a series of dives at three different sites in the Alaminos Canyon lease blocks, off the coast of Texas.

A few of the hard and soft corals in the Coral Garden area in GC 852. Click image for larger view and image credit.

A large aggregation of tubeworms (mostly Escarpia laminata) attached to carbonate blocks at 2,200-meter depth in Alaminos Canyon lease block 645. In the foreground is the Bushmaster collection device, which is attached to the front of the Alvin submersible. Click image for larger view and image credit.

At Alaminos Canyon (AC) 818, in 2,800m water, we have a tubeworm growth study underway and have also seen, but not collected, what is almost certainly a new species of clam with sulfur-oxidizing symbionts. Another site, AC 645, was the first deep water hydrocarbon seep community discovered in the Gulf of Mexico, and where we banded some tubeworms and mapped mussel communities way back in 1992. We found our 1992 study area during the last dive of the 2006 expedition, so we will return here and document the changes in the communities and growth of the worms that has occurred over the last 16 years!

Another site, in AC 601, hosts a large lake of brine that covers about 17,000 square meters of the sea floor. The sediments here had some of the most extreme chemistry and strange microbial activity of any site we visited, and the chemists and microbiologists are excited for another set of samples from this site.

By the end of this expedition, we will have a very good understanding of the biodiversity of the communities on the deep hard grounds and seeps in the Gulf of Mexico, and their relation to the complex geology and geochemistry of the region. We will have the samples needed to begin unraveling the relationships among the populations at different sites and the data to estimate growth rates and calculate ages of some of the key species. We will also have collected a large quantity of “ground-truth” information, relating what can be detected by remote sensing to what is actually present on the sea floor. This will provide us with a vastly improved ability to predict the occurrence of seep and coral communities in the deep sea, based on geophysical, geochemical, and satellite data collected from both on and above the surface of the ocean.