Stephanie Lessard-Pilon (left) and Julia Zekely use a sieve to carefully separate the macrofauna and meiofauna. Click image for larger view and image credit.

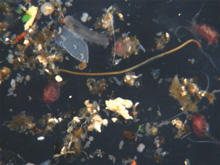

This microscopic image of various meiofauna. The red dots are copepods, and the long worms are nematodes. The pink worm (along the left edge) is a juvenile polychaete worm. Click image for larger view and image credit.

Meiofauna: Don't Forget the "Little Guys"

June 27, 2007

Julia Zekely

University of Vienna

27° 11.20 N

92° 7.51 W

To even begin to grasp the ecology of faunal communities, you have to first know what lives there. In many cases, scientists investigate only the macrofauna (organisms larger than 1 millimeter [mm]). Unfortunately, this often overlooks a significant portion of the organisms in any given area. The meiofauna consists of microscopic protists and tiny animals between 1mm and 32 micrometers (µm). (A micrometer, or micron, is 0.001 mm.) During this cruise in the Gulf of Mexico, I am collecting meiofauna associated with both tubeworm and mussel aggregations. These assemblages create three-dimensional systems, where smaller macrofauna and meiofauna live, feed, and/or find refuge from predators. I will use the information collected during the cruise to compare biodiversity and community structure between these two types of chemosynthetic communities.

Meiofauna is primarily composed of small round worms (the Nematoda), numerous crustaceans (like Copepoda and Ostracoda), as well as Gastrotricha and even protists, such as Foraminifera. Though these groups are found in the meiofauna and macrofauna, there are other unique taxa found only in the meiofauna. Examples of these are the Gastrotricha and Loricifera.

During this cruise, the science party is focusing on habitats at the sea-floor/seawater interface. The meiofauna near the sea floor surface are called the "meiobenthos." Despite playing a very important role in nutrient cycling in both freshwater and marine ecosystems, the meiobenthos are often overlooked because of their small size and the difficulties associated with collection and sample processing.

Julia Zekely shows off a tiny crab collected with the "Bushmaster Jr." sampling device. The species is found in association with tubeworm communities. Click image for larger view and image credit.

This organism is a typical undescribed harpacticoid copepod. Though this particular specimen was collected at a hydrothermal vent site, the same family may actually be found at seeps as well. This specimen, all of 0.4 millimeters in length, was sieved from the sediment surrounding a mussel collection. Click image for larger view and image credit.

On this cruise, we typically get our meiofauna samples "off of" the larger macrofaunal collections of tubeworms and mussels. When tubeworm and mussel aggregations are brought onboard the ship, scientists carefully rinse off the tubes and shells. The meiofauna, now in the rinse water, and any sediment in the collection devices are carefully poured through a set of mesh sieves (1 mm and 32 µm). The various mesh sizes separate the "larger" macrofauna from the tiny meiofauna.

Since we are collecting so many samples during this cruise, it is impossible for us to process all our collections at-sea. On many occasions we are also "fixing" samples in a 10% formalin solution. This will preserve the samples until we have time to finish the job. As soon as we get back to the lab in Austria, I will begin mounting many of the organisms on slides and identify them using light microscopes.

Counting the meiobenthos will not be an easy task. In past work, we’ve found abundances can reach up to 1,000 per 10cm2 at cold seeps. While counting these organisms, we will also be working to identify a subset of these organisms to the species level. This information will be used to estimate species richness and diversity at both tubeworm and mussel communities.

Even though these organisms are tiny, our microscopes our powerful enough to get a good look at the miniscule mouthparts of many of them. Through previous work at other extreme environments, like deep-sea hydrothermal vents, we have found only bacterial or deposit feeders, scavengers, and a few parasites. We haven’t yet found any predators among the meiobenthos. Who knows what little treasure we’ll find this time?