A submarine landslide exposed this mudstone scar devoid of marine life and sediment, indicating recent mass-wasting activity.Click image for larger view.

Aggregations of sea cucumbers and sea stars on the soft, muddy bottom of Astoria Canyon. Click image for larger view.

Sea Cucumbers Galore!

June 30, 2001

Jeff Goodrich, Teacher-at-sea

Earth Science Teacher

Lake Oswego High School

Lake Oswego, Oregon

and

Susan Merle, Geological Research Assistant

CIMRS Program, Oregon State University

Vents Program, Pacific Marine Environmental Laboratory, NOAA

ROPOS dive R598 is the third dive along the southern wall of Astoria Canyon in depths ranging from 200 to 650 meters. After adapting survey methods to this new environment, the transects began. The dive started with quantitative fish and invertebrate transects along the upper rim of the canyon wall. These transects were performed during daylight hours in light of concerns that behavioral changes in the fishes after dusk may bias the data. Fish abundances along the wall were surprisingly low, based on comparisons between similar areas along the west coast. However, we observed large numbers of Pacific halibut for this area. Intense geologic and invertebrate investigations occurred throughout the night. In general, the walls were mud-covered with large numbers of tube-building sea cucumbers, sponges, anemones, and brachiopods. A striking submarine landslide was observed along one of the steepest portions of the southern canyon wall, exposing fresh surfaces of rock. The high sedimentation levels in this area and the lack of sediment and animals settled on the rock surfaces indicates this was a recent mass-wasting (landslide) event. These events could be common in this canyon because these rocks are soft (mudstone or clay) and the slope is steep. The canyon floor had incredible aggregations of sea cucumbers and sea stars numbering in the hundreds in concentrated areas, indicating high amounts of nutrients available in these soft sediments.

Other operations over the last 24 hours include several CTD's (conductivity, temperature and density measurements), bio-acoustic profiling, and IKMT (Isaacs-Kidd Mid-water Trawl). The IKMT captured crab larvae, juvenile rockfish and euphausids (krill). Krill are prey for fish, seabirds and marine mammals, forming a critical link in marine food chains.

Brian Tissot, marine ecologist from Washington State University in Vancouver, Washington.

Shortspine thornyhead rockfish snuggled amongst brittle stars, a sea star, smaller brittle stars, and sea cucumbers with white tentacles on a mixed rocky and mud-covered habitat. Click image for larger view.

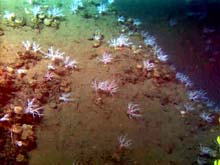

Fields of white sea cucumbers, tentacles outstretched into the current, filter-feed from the nutrient-rich water of Astoria Canyon. Click image for larger view.

Interview with Brian Tissot

Marine Ecologist, Washington State University, Vancouver

Ocean Explorer Team: What research are you conducting at Astoria Canyon and farther south at Heceta Bank?

Brian Tissot: Our lab's working on invertebrate ecology. We're trying to quantify and understand some of the ecological relationships between invertebrates, especially crinoids, in their different habitats. We're also looking at the relationship between invertebrates, their physical habitat and how that relates to the abundance of fish. There's a real need, especially with groundfish, to define the concept of essential fish habitat. One of the reasons it's so important is because there is talk about putting marine protected areas, or reserves, along the west coast. We want to know what the important habitats are so we can determine what areas should be protected.

Ocean Explorer Team: Is there anything unusual about the Ocean Exploration program compared to other cruises you've been on?

Brian Tissot: Here, we're really just exploring. We don't know anything about what's out here. I think some of the things that we've seen are really exciting in terms of the invertebrates. It must be very rich at the bottom of the canyon because of the large number of organisms that are burrowing in the bottom. The incredible abundance of sea cucumbers and sea stars suggest that there is a huge amount of organic matter coming into the canyon from two major sources. One is the Columbia River, which drains thousands of square miles and the other is the counter-current coming up the canyon from the deeper ocean. The mixing of these different sources of nutrients makes for a unique situation. There is no other canyon like Astoria anywhere.

Ocean Explorer Team: Sounds like there's a lot left to be learned about submarine canyon ecosystems.

Brian Tissot: Yes. It's a really exciting opportunity. We really don't know anything about the ocean. I think a lot of kids these days have the impression that we've discovered everything, that science is over. Far from it! This is obviously just the beginning of a huge endeavor. There's a lot to look for and a lot more research needs to be done. We'll need more marine biologists and I believe in the next 100 years, with the changes in technology, we'll have that opportunity to explore the rest of the ocean. Oceans cover most of the world and we're facing a lot of problems with space, food, and pollution. As we learn more about the ocean, I hope we conserve it before we overexploit it. Unfortunately, over-exploitation is our history.

Sign up for the Ocean Explorer E-mail Update List.