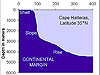

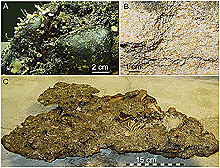

(A) Broken Mn-phosphorite pavement slabs from the area near the Wreckfish Cave dive site. (B) Mn-phosphorite pavement slab, with an octocoral colony, collected from the top of the Sponge Cliff dive site. (C) Relict (ancient) sediment ripples that have been encrusted by iron-manganese (Fe-Mn) oxides. Click image for larger view.

The Sea Floor Rocks!

August 30, 2004

Leslie R. Sautter, PhD

Department of Geology

College of Charleston

On the Estuary to the Abyss Expedition along the "Latitude 31-30 Transect," we have been amazed at the variations in sea-floor habitat across the Blake Plateau, which ranges in depth from 500-900 m. Most of our dive locations were chosen based on previous hydrographic surveys -- U.S. Geological Survey side-scan sonar from the early 1990s -- and supplemented by visual observations made from the Navy NR-1 submersible. The deep-sea physical habitats we have encountered range from sediment-starved rock pavement, to terraced and vertical cliffs of inter-bedded (multi-layered) rocks, to enormous rippled dunes.

Foraminiferan limestone can be seen as an overhanging ledge in the upper left portion of this downward-looking view from the Wreckfish Cave dive site. Numerous large red bream congregated beneath one of the ledges of the Barrelfish Cliffs dive site. Click image for larger view.

At the south end of the Charleston Bump beneath the Gulf Stream, we encountered broad, flat expanses of manganese phosphorite rock (Mn-ph), referred to as "pavement." This pavement is often broken into angular, tabular plates. Mn-ph is formed from the chemical precipitation of phosphate (PO44-) directly from the seawater. This painfully slow, molecule-by-molecule process may form nodules or it may coat an existing layer of rock or sediment.

The Mn-ph pavement is formed as thin, dense, very hard, sheet-like layers that are extremely resistant to the erosive forces of currents. This pavement has almost no recent sediments deposited on it, because the current is swift and keeps the rocks swept clean of any loose particles. In areas of broken pavement, some accumulation of biogenic sands (consisting of shell and other material formed by once living organisms) can be found. This often results in the formation of small areas of rippled sand. However, most of these accumulations are not recent, and they have been coated by precipitation of iron and manganese oxides, making them appear reddish-brown.

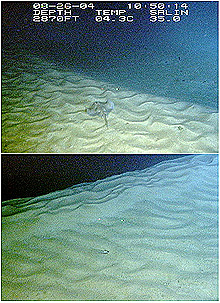

Two views of the rippled dunes at the Sandy Tongue dive site. These sands are a hundred percent biogenic, comprised of shells and tests of small organisms, such as foraminifera, mollusks, and echinoderm spines. Dunes at this location measured 3-4.5 m high. Dunes at the Coral Mounds dive site were as high as 15 m. Click image for larger view.

The terraced and vertical cliffs give us a look at the underlying rock layers that are exposed beneath the pavement. Most cliffs are capped by a thin, erosion-resistant Mn-ph layer on top of a type of limestone that is made of shells, or "tests," of microscopic organisms called foraminifera. "Forams" are single-celled protozoa that live in the surface waters of the ocean. When they die, their tests settle to the sea floor and become part of the geologic record. If these sediments become cemented together, they form foraminiferan limestone that is exposed in cliffs and often creates overhanging ledges that provide excellent habitat for fish.

East of the Gulf Stream, where the Blake Plateau descends to depths greater than 750 m, the currents are weaker, and more accumulation of sediments is possible. These sediments, rich in foraminifera and coral rubble, are thick on the sea floor, and they have formed enormous sand dunes -- some larger than 15 m high!

The origin and formation of these dunes is somewhat of a mystery. Extremely strong bottom currents, such as those created by the Gulf Stream, would normally be required to form such large, mobile features. The Gulf Stream, however, is west of this duned area. Perhaps hurricane-induced currents can shift these sands into the large-scale features we have observed. Some of these dunes are covered with ripples and have few rocks exposed. We collected one rock from the Popenoe's Coral Mounds site, which served as a foundation for a lovely bamboo coral. This rock was made of foraminifera tests that were poorly cemented from the surrounding foraminifera-rich sediment.

Sessile invertebrate communities, like sponges and corals, provide habitat for higher organisms, such as fish and large invertebrates. They need hard bottom or rock formations to hold onto in this environment, which is dominated by swift bottom currents. With each dive, we discovered new sea-floor habitats and brought back the different rock types that form their foundations. Only with the continued aid of submersibles, remotely operated vehicles, and high-resolution mapping (like multibeam sonar) will we be able to truly understand the complex and varied sea-floor seascapes of the Blake Plateau and the marine life that dwells there.

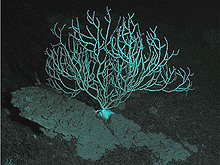

The only rock observed at the Popenoe's Coral Mounds dive site was a loosely cemented foraminiferan "ooze." A bamboo coral used this lonely outcrop as a solid base on which to live. We collected only a small portion of this rock. Click image for larger view.

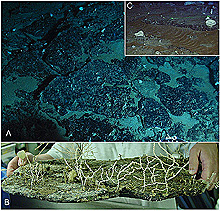

Of the eight rock specimens collected, three rock types were found: (A) Mn-phosphorite pavement rock, some of which included large nodules; (B) loosely cemented foraminifera ooze; and (C) well-cemented foraminiferan limestone that formed ledges and overhangs. Click image for larger view.

Sign up for the Ocean Explorer E-mail Update List.