Styrofoam coffee cups (front row) are compressed after descending 3,000 ft to the ocean bottom on the Johnson-Sea-Link II. The three styrofoam wig heads were originally identical in size. The middle head was taken down to about 2,000 ft depth, and the head on the left was taken down to 3,000 ft. Click image for larger view.

Excitement, Realities, and "Bubba"

August 27, 2004

Jeff Jenner

Web Coordinator

NOAA

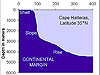

In the past week, we have visited the deeper side of the Gulf Stream along the Latitude 31-30 Transect. The currents down there are swift, by deep-ocean standards. The video taken by the Johnson-Sea-Link II camera shows a sea floor that looks surprisingly like the desert southwest. It is quite barren, having been scoured of most of its sediments from thousands of years under the Gulf Stream. The rocky outcroppings hang out over the sea floor like the rounded, wind-blown rocks in the desert.

This cruise is truly an exploration, and the atmosphere aboard ship is very special.

Yesterday, our educator-at-sea, Katrina Bryan, strapped Styrofoam coffee cups and wig heads to the outside of the sub during her dive. She wanted to demonstrate the tremendous pressure created by 3,000 ft of water above the sub. At that depth, the pressure is a hundred times that of air at sea level. Styrofoam is filled with billions of tiny air pockets, so it shrinks under pressure. The coffee cups shrank to less than two-inches tall. The deep ocean is also very cold. We saw bottom temperature readings as low as 4ºC. Obviously, a human being would not live more than a few seconds outside the sub.

Like the desert, the sea floor on the Blake Plateau is a harsh environment; but when you study desert or deep-sea ecosystems, you actually see an amazing diversity of life. In fact, there is not a single speck of ocean that does not contain at least some life. It’s just a lot harder to get to in deep water.

As I wrote that sentence, I heard graduate student Christina Ralph, who was sitting next to me, say: “It looks like just a bunch of sand, but they’re constantly seeing new things.” She was analyzing the video brought up a couple of hours ago from the submarine. She will study over 40 hrs of tape during this expedition. As I wrote that sentence, I also heard Scott Meister’s voice on the video: “That’s the biggest sea anemone I’ve ever seen. I don’t know how we’re going to do this.” He was referring to how the sub pilot was going to pick up the animal with the suction attachment on the sub’s mechanical arm.

And, as I wrote that sentence, I looked over at the two 5.5-in DV tape monitors to my left just in time to see the sub’s mechanical arm pick up the biggest, ugliest, slimiest fish I had ever seen. The numbers at the top of the video screen read: Depth 2,977 feet, Temp 10.3 C, Salinity 35.3. I was duplicating the second hour of video tape from Josh Loefer’s dive -- and that fish was unbelievable!

Byron White later identified the fish as a Sladenia shaefersi, or Shaefer’s anglerfish. Only two specimens have ever been seen throughout the world -- one off the coast of Columbia in 1976, and the other one later near Aruba. Ours is the third ever seen, and we found it very far north of its known range. Detailed study of this single fish, along with all the other data that we are collecting around where we found the fish (temperature, salinity, depth, bottom type, other species around it), will be enough for a full journal publication.

Josh received credit for catching the Shaefer's anglerfish along with the privilege of designating this particular specimen by a unique identifying name: “Bubba.”

The third known specimen of Sladenia shaefersi, or Shaefer’s anglerfish, ever found. The Johnson-Sea-Link II pilot, Tim Askew, Jr., secured the fish with the suction tube on the sub’s mechanical arm, then lifted it into a collection bucket. Note the red and green laser dots from the sub’s camera, which are 25 cm apart. Click image for larger view.

Once on board ship, “Bubba” was measured, weighed, studied, and preserved. A sample of his bacteria was also taken for Mark Mitchell’s antimicrobial study. The “fishing poles” on his head are illiceum, or the first and second spines of the dorsal fin. These attract prey, which swim just above his huge mouth. He then sucks the prey in. Note the centimeter scale markings on the white table. Click image for larger view.

Josh also brought up a basketball-sized bush of Lopheila prolifera coral that was lying by itself in an otherwise empty landscape. Though the coral had been dead for quite some time, the bush structure provided shelter for many organisms -- possibly hundreds of different species, most of which we would need a microscope to see.

While watching the video of Scott’s dive, Josh identified a frilled shark (Chlamydoselachus anguineus) swimming over sea bottom that was covered with tiny sand dunes. This species has been, on rare occasion, caught or taken in bottom trawls. To the knowledge of everyone on board, however, this was the first time anyone had ever seen the rare species in its natural habitat.

The Johnson-Sea-Link II mechanical arm picks up a Lophelia coral bush. Two eels lived underneath and scurried away when their coral home was taken away. Click image for larger view.

The first known video footage of a frilled shark (Chlamydoselachus anguineus) in its natural habitat. Click image for larger view.

Someone from my hometown in central California wrote to me yesterday and asked me what is was like to be out on the ocean, exploring it. I wish I could just say that 16- to 18-hr days are fun (which they are), that we have gourmet meals served to us every day (which we do), that the weather has been perfect (which it has), and that we have one exciting moment after another (which we do). Once in a while, however, the satellite phone rings and reminds us of how isolated we are when things go wrong at home. Just after midnight, we suspended science operations for 24 hrs and steamed full speed (11.5 mi per hr) 140 nautical mi to the Charleston ship channel, where a small boat from the South Carolina Department of Natural Resources came along side and took one of our scientists back to James Island.

Now, 24 hrs after I began writing this log, we are steaming at full speed 120 mi back to our next dive. Dr. King just came into the lab to tell us that we are about to head straight through a tropical depression with winds forecast to 30 knots. Everyone is now packing things up and tying them down. Exploring the ocean is certainly exciting, but the harsh realities of being out here are among the very reasons we are still exploring it.

Sign up for the Ocean Explorer E-mail Update List.