The Joys and Challenges of "Underwater" Photography

August 23, 2004

Susan Thornton-DeVictor

Wildlife Biologist II

Southeastern Regional Taxonomic Center

Marine Resources Research Institute

Charleston, SC

As the submersible floated alongside the starboard side of the ship, as it always does for recovery after a dive, I watched in anticipation and wondered what intriguing things were contained in the platform buckets. There had been limited communication between the sub and the bridge due to some mechanical problems, so we did not know they had collected until we actually removed the buckets from the sub.

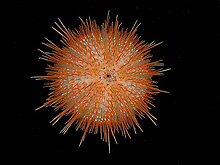

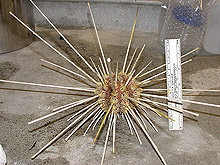

I had specifically requested some crinoids (sea lilies, a relative of sea stars) that we observed on the previous dive, so I was hoping one was collected. (I am an "invertebrate person," as opposed to a "fish person," which is a light-hearted division between some of the scientists on board. This does not mean that I have no backbone; just that I study things with no backbones.) The sub brought us two sea urchins, some sponges, a rock covered with octocorals -- and a crinoid. Although this may not seem particularly exciting, I suddenly found myself with excellent subjects for the task I had at hand. I spent the next few hours working with these animals to photograph and preserve them.

A very large sea urchin brought to the surface by the Johnson-Sea-Link II. Click image for larger view.

Photographing live specimens

During this cruise, I am photographing many of the animals that we bring aboard ship and keep for scientific study. Photography of live specimens can be an important archival and educational tool, and it allows a view of a specimen that few people would otherwise be able to see.

In the past, I have photographed marine specimens using underwater photographic equipment, such as a Nikonos V, digital cameras and housings, and underwater video systems. This equipment provides a look at the underwater environment in which a specimen lives as well as its appearance underwater, which may be very different than its appearance after it is brought to the surface.

Underwater cameras have limitations. For instance, they are limited to clear water conditions and high light environments (natural or artificial). Capturing quality images in silty or deep water is very difficult or sometimes impossible. Digital and film cameras are also generally limited to depths to which a scuba diver can safely descend. Furthermore, marine animals are generally camera shy and will try to escape -- as if avoiding paparazzi -- from humans, lights, and subs, if they can. I have many photos of the ocean floor where an animal sat one second prior to shutter release.

During the last two years, I have changed my strategy. I now do my "underwater" photography primarily in our taxonomic lab -- on land. Because many invertebrates lose their pigments when they are preserved, we have been photographing them while they are still fresh. Identification of an animal is usually easier with its true colors intact, and these images are useful in publications and other visual media.

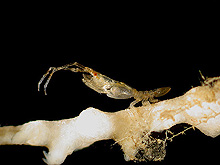

An arcturid isopod clings to a branch of an octocoral. This photo was taken using a camera mounted to a microscope. The field of view of the photo is 3 mm. Click image for larger view.

Here's my method. To photograph live specimens, I use a Nikon Coolpix mounted on a copy stand or microscope, along with artificial illumination. I use the copy stand for larger animals (more than 2 cm in length) and a microscope for smaller specimens. I immerse the animal in water in a bin under the fixed camera. This reduces bright spots caused by the lights on the wet surfaces of the animal. A black fabric background dampens the shadows cast by the specimen and provides a consistent, neutral background that allows the colors and body outline to stand out. Artificial illumination provides sufficient light, if the shutter speed is slow enough.

How to slow down a crab

This system is very good, in theory, but there are still many challenges, mainly involving the animals themselves. Live animals that are active and moving are generally not cooperative. Crabs in particular love to scurry away from the camera view, often hiding under the black background. Even sea stars can move fast enough to appear blurry in a photograph.

There are several ways to relax animals without harming them. Echinoderms (sea stars, sea urchins, sand dollars, etc.), cnidarians (sea anemones, corals, jellyfish), mollusks (clams, snails, slugs, octopi, squid), and some other invertebrates relax when placed in a solution of magnesium chloride, which is similar in composition to seawater. After a few minutes in this solution, many animals slow down considerably and often allow their tentacles and other constrictive body parts to expand so that they are in full view. Once we are finished photographing them, we can revive them with regular seawater. (If we are planning on preserving them, we sometimes put them in preservative in this state so their expanded body parts do not constrict.)

Crabs and other crustaceans are not so cooperative. The most common way to calm them is to chill them. They can be placed in a refrigerator for a while, and if photographed quickly (before they warm up), they are pretty cooperative. The opposite is true for deep-water crustaceans. Deep-water environments are often cold, so putting the animals in warm water slows them down.

Sessile invertebrates (those that are fixed to something) are easier to photograph. Still, there are challenges. For instance, sponges are often beautifully colored, but they have sharp spicules that may embed in your skin when handling them. They immediately dirty up the black background when sediments fall out of their pores, requiring more image processing to remove the clutter from the picture.

Branching soft corals do not move, but it is hard to determine the correct exposure for them, because they often have no central area on which to focus. It is also difficult to obtain the correct exposure settings for animals that are very dark, white, or transparent. Holothurians (sea cucumbers) are extremely slow moving, but some are either neutrally buoyant or just slightly negatively buoyant, meaning that they sink slowly. If there is any water movement -- and there generally is on a moving boat -- a sea cucumber will tend to roll around like a hot dog on a plate as you walk from the grill to the kitchen.

Nothing is more challenging than photographing squids and octopi. Their immediate response to stress is to ink the water, then crawl away and stick to the side of the tank. It is amazing how strong they are. Unfortunately, they do not retain their coloration when cooled or frozen, because their appearance is often highly dependent on their "state of mind" or reaction to their environment.

Susan DeVictor photographs marine organisms that have been brought up to the ship. Expedition scientists used various specimen-collection methods, including a manned research submersible, bongo net trawl, neuston net trawl, grab sampler, and dredge trawl. Click image for larger view.

One of the most exciting forms of photography is through the microscope. This allows us easily to view very small organisms that we cannot normally see. Some of these animals are absolutely fascinating, especially those that are larval stages or rarely seen because of how deep they live.

Being on a ship adds a new level of excitement to specimen photography. If you are prone to seasickness at all, looking through a camera lens or microscope may push you quickly over the edge. Also, on a moving boat, the water in the photography bin is never still or level. The vibration of the engine may cause tiny riplets on the surface and often vibrates specimens, too.

Photography is a useful and rewarding way to archive marine specimens collected from places that are very difficult to get to, like the deep ocean. I enjoy the opportunity to work with animals that few people have seen alive, and I hope to share my images with the scientific community and public through our Web site and publications.

Sign up for the Ocean Explorer E-mail Update List.