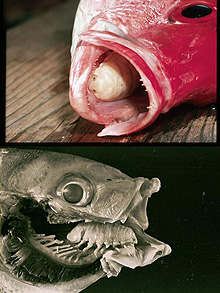

Some species of isopods live parasitically on fish, either externally or internally. Click image for larger view and image credit.

Transitions to the Deep: Isopods From the Coasts to the Abyss

Rachael King

Southeast Regional Taxonomic Center

South Carolina Department of Natural Resources

As we travel from shallow marine coastal areas, down onto the continental shelf, and finally into the depths of the abyss, we can make this observation: changing environments mean changes in appearance for many marine invertebrate groups, including isopods.

This makes sense when you consider the differences in these environments. Shallow waters are relatively warm, species-rich places, abundant in nutrients as well as predators. Deeper waters are more mysterious. We know they are cooler and perhaps not as abundant in food. (Food there comes mostly from organic matter slowly filtering down through the water column.) Another factor is that the deep ocean is darker and is home to different types of predators.

Not surprisingly, deep-water animals look and act quite differently from their coastal and shallow water relatives -- and it's because of the differences between deep and shallow water. In this summary, we will look at how the differences manifest in isopods.

What are isopods?

Isopods are an order of marine invertebrates (animals without backbones) that belong to the greater crustacean group of animals, which includes crabs and shrimp. Isopods are one of the most morphologically diverse of all the crustacean groups. They come in many different shapes and sizes, from micrometers to a half meter in length. They also live in many different types of habitat, from mountains and deserts to the deep sea. The most familiar isopod is probably the terrestrial pill bug (sow bug or wood louse), which can be found scurrying around any back yard in moist, dark conditions.About half of the known species of isopods live in the ocean. Some are large and spiny and live in the deep sea, while others are very small and live as parasites on fish. Many more live in coastal and shelf waters, moving around on the sea floor or living in plants.

Coastal isopods

The "wharf roach," or "sea roach" (Ligiaexotica), is a common isopod often found running around on pier pilings and rocks at high tide. It is a scavenger that feeds on organic matter that it scoops up from rocks and pilings. This isopod is terrestrial, which means that it lives on land. Growing to about 3 cm in length, Ligia exotica has large eyes and long antennae for sensing what is happening in its immediate environment. Also, it can run extremely fast. These are handy features to have, considering that it needs to be aware of predators, such as birds.

The "wharf roach," or "sea

roach" (Ligiaexotica),

is a common terrestrial isopod, often found running around on pier pilings

and rocks at high tide.

The marine isopod Synidotea laevidorsalis can be found

on boat slip pylons, among seaweed and

hydroids.

A marine isopod, Synidotea laevidorsalis must be submerged in water to breath, because its specialized breathing structures extract oxygen from water. Synidotea laevidorsalis can be found on boat-slip pylons among seaweed and hydroids; and it grows to about 2 cm in length. Like Ligia exotica, this isopod is a scavenger. The camouflage pattern on its body helps it to blend in with its environment, making it harder for hungry fish to pick it off of the seaweed. Also, it has tiny claws on each leg that help it cling to algae in the water, and it can swim between plants by flapping its paddle-shaped distal (positioned away from the central part of the body) appendages.

The arcturid isopod, Astacilla spinata. Arcturids (family Arcturidae) have developed a unique body type that enables them to live among plants and plant-like animals. Click image for larger view and image credit.

Isopods from the continental shelf and open ocean

The arcturids (family Arcturidae) are marine isopods that have developed a unique body type, enabling them to live among plants and plant-like animals (such as bryozoans and sponges) as filter feeders in coastal and shelf waters. These isopods are cylindrical, rather than flat. Their posterior legs are adapted for clinging, while their anterior legs are long and hold rows of long hairs for filtering food. Their bodies are often elongated at the fourth segment so that they are able to tilt upwards and get their anterior legs higher in the water column (to get more food). They swish their anterior legs around and the hairs collect from the water small food particles, which are then sent to the mouthparts.

Some species of isopods live parasitically on fish, either externally or internally. One particular group, the cymothoid isopods, can live inside the mouth of a fish. Scientists believe that these isopods hook their legs into the base of the fish’s tongue, causing it to wither and eventually fall off. This leaves room for the isopod to live. (Scientists believe this does not affect the fish’s lifespan!) Some species live off the blood of the host fish, while others feed off the mucus within the fish’s mouth. The mouth parts and legs of all these isopods are well adapted for clinging to the host.

Bathynomus giganticus lives off the Gulf of Mexico and the South Atlantic coast of the U.S. Like many deep-sea animals, it is larger than its shallow-water relatives.

Isopods from the deep . . .

The largest isopod species are those from the genus Bathynomus. These animals live in the deep-sea, and (like many animals that live there) they are larger than their shallow-water relatives.

One such species, Bathynomus giganticus, is found in water up to 1,000 m (off the Gulf of Mexico and the South Atlantic coast of the U.S.); it can grow up to about 28 cm in length. It is usually caught in baited traps, which it enters to scavenge fish carcasses. It actively preys on smaller animals as well as scavenges on anything organic that drops to the sea floor.

It pays to have adaptable feeding strategies when you live in such a resource-poor environment.