To the Mystery Wreck — at 7,000 Feet!

September 7, 2009

Lori Johnston

Harry Roberts

Louisiana State University

Sheli Smith, PhD

PAST Foundation

![]() This video shows the wreck at 7,000 ft depth.

This video shows the wreck at 7,000 ft depth.

The ROV Jason entered the water right on time at 4 p.m. EDT with a splash, and began its descent into the clear blue waters of the Gulf of Mexico. Our pilot Bob and watch chief Rob watched the video monitor with eager anticipation as the remotely operated vehicle (ROV) Jason descended the 7,400 feet (2,255 meters) to the wreck site. As Jason descended into the abyss, the rays of sunlight faded as one by one the various colors of the rainbow were gradually absorbed into the ocean’s depths. At 400 ft (122 m) , light from the surface ceased, and only the lights of Jason illuminated the depths.

The deep ocean is a different world: a silent world, a cold world, and a world of darkness. Despite the environment, so alien and inhospitable to human survival, other creatures thrive. A host of organisms fluttered past the camera eye of Jason all the way down on the seafloor, calling the ocean bottom home. Crabs, anemones, and sea cucumbers are just some of the animals the biologists hope to study.

Our mission for the day was to explore an unidentified shipwreck. Known as the “7,000-Foot Wreck,” the wreck actually sits in 7,400 ft (2,255 m) of water. The site represents the deepest historic shipwreck ever discovered in the Gulf of Mexico.

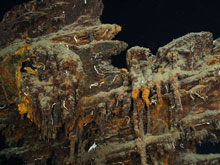

A close-up of the wale (a ridge of planking) and hawsehole (an opening for anchor rope or cable) the top of the stem. Click image for larger view and image credit.

A Recent Discovery

The anomaly on the bottom was first noted during a deep-tow survey in 1986. However, it wasn’t reported as a “potential shipwreck” until 1992. Earlier this year, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution’s Sentry autonomous underwater vehicle (AUV) confirmed the site as a shipwreck. From that survey, we know that the site represents the remains of a relatively small sailing vessel. The ship is about 60 ft long and 18 ft wide. Along the axis of the wreck are several prominent features, including the stempost, the windlass and steering mechanism at the stern. The two bower anchors were observed in place on either side of the bow. Armed with this scant information, we headed off to study the mystery wreck. After 70 minutes, Jason touched down about 20 m (66 ft) off the bow of the shipwreck.

Rob Church and Rob Westrick joined Sheli Smith and the Jason team in the Virtual Van, dubbed the "Zen Van" by Lori and Sheli, anxious to study this shipwreck. He plans to write up this site report, so he was eager to grab every minute he could get to investigate the remains. All the scientists onboard the NOAA ship Ronald H. Brown eagerly awaited collection of data both natural and cultural off this wreck because of its unique depth. Who knows what information will be learned, what secrets will be revealed, and what mysteries might be solved before the end of the days activity.

In the pre-dive science meeting, Erik Cordes and Rob Church, the lead scientists for each team, carefully laid out the evening’s plan, delineating a timeline and tasks. Rob Westrick gave a brief history of the wreck’s discovery. Like a well-choreographed dance, we moved in and out of the van, setting up a site mosaic, cores, biological transects, and close-up study of the hull and the remains. By Dive 2, we are old pros at the activities necessary to perform a dive: first, the reconnaissance; then the mosaic; then the bio transects; and finally, recovery of both biological and cultural specimens.

Wreck-flying with Jason

Cruising down the wreck, we could readily see that she settled on her portside. A large sediment berm had built up along the elevated starboard hull. The stunning sharp bow, reminiscent of the famous nineteenth century clipper bows, rises out of the seafloor and stands proud, with rigging still attached. The relatively clear water and bright lights of Jason revealed a spectacular image of what was once a beautiful sailing vessel. Long thin anchors lay just aft of the bow, having fallen from their secured position at the bow. Traveling aft, we see the windlass drum is upside down with its knees still attached, while lodge knees and smaller artifacts lay scattered among the hull debris.

Aft of the windlass lies the remains of the water tank; along the centerline sits a ring and boom yoke, most likely from the main mast. Rigging lying out to the portside suggests that both the main mast and foremast collapsed, carrying the standing rigging with them. Today, only the fragments of the tarred, wire cable rigging remain.

Flying aft, we see that a large fragment of main deck sits tilted at a precarious angle and standing proud off the wreck. Upon close inspection, we discover another anchor lying against the deck. The starboard bilge-pump pipe holds aloft the entire conglomeration of anchor and deck.

Moving further aft, we see the remains of the booby hatch and what we suddenly realized was the ship’s compass. Rising off the ship is a beautifully intact, patent steering gear system complete with intact well. Just off the stern of what we now know is about a 60-ft schooner, or ketch, is the rudder, with exposed gudgeon entangled in steering cables.

Jake Schidner of West Florida University gingerly retrieves the compass. Click image for larger view and image credit.

Life at 7,000-ft Depth

Excited to investigate the life at this depth, biologists Erik Cordes, Cheryl Morrison, and Peter Etnoyer eagerly took over the flight as soon as the mosaic was complete. Lori’s micro biological platform and short-term experiment were also set down in the stern to ensure the short experiment was given enough time to collect data before we recovered it at the end of the dive. Once the cores were complete, the collection of biological specimens began. On through the night, the scientists and crew cruised up and down the wreck, taking samples and photographs to capture data.

The 7,000 Foot wreck had a spectacular array of rusticles both at the bow and on the steering mechanism at the stern. Lori and pilot Matt carefully collected numerous specimens using the small basket. The fragile microorganism presents quite the collection challenge ,testing the articulating arms and collection tools of Jason and its pilots. A cheer went up both inside the van and in the main lab as we all watched Matt save a small rusticle that spilled out onto the top of one of the side tray bio boxes. Using the basket like a putter, Matt skillfully tapped the rogue rusticle into the open quiver alongside the box and then neatly capped the specimen container with a plug, for the ride up to the surface.

The card of the compass is still intact revealing the manufacturer and date of the compass patent. Click image for larger view and image credit.

Collecting Cultural Artifacts

By 4 a.m. EDT the team, led by Rob Church, was ready to begin collection of the diagnostic, cultural artifacts. Jack joined us in the van to discuss which objects would provide the most information regarding the date of the wreck and identity of hull. Between us, we decided that the compass, a sophisticated navigational instrument, almost always is etched with maker marks and dates. The challenge then turned to Bob to retrieve the artifact from the silt without damage. The van — often the scene of laughter and running, staccato verbal notes of information — became very quiet. The pilots had worked throughout the day to remedy the clumsy glove issue. Their solution was to shrink wrap the pincers of Jason's mechanical arm with plastic. It worked beautifully.

Bob began by slurping silt off the gimbaled compass, which was turned away from the cameras. Once cleared, he gingerly tugged at the gimble ring to discern if the compass was free. It was. Absolute silence prevailed as Bob slowly and ever so carefully tipped the compass toward the camera. A whoosh of air escaped everyone’s lungs as the glass face with intact compass card emerged from out of the silt. Clearly printed around the directional needle were the letters "BOS." “Boston!” Sheli said. “The compass was manufactured in Boston.”

Now came the critical moment. “We know you can dance this baby on the head of a pin, Bob,” Sheli coaxed. Either a groan or chuckle came out of Bob. We weren’t sure.

Again the van became stone silent as Bob found a delicate hold on the fragile piece and lifted it to the waiting bucket on Jason’s "front porch." With painstaking skill, he held the ring and compass in the grip of the arm, lifting up and back into the bucket. Just before setting the compass into the bucket, he realized a weight was sitting inside. So, to add even more tension to an already harrowing moment, he had to hold the compass absolutely still with the starboard arm while using the port arm to reach across the porch and pluck the weight out of the bucket. No one said a word; the van was silent except for the whirr of the fans. Finally, with the weight removed and set securely beside the bio chambers, Bob once again skillfully moved the compass to the bucket and then down into the waiting foam bedding. A cheer went up as the compass set down safe for the ride to the surface.

Copper from the transom will help define the age of the vessel. Click image for larger view and image credit.

Carrying Precious Cargo

At 7:50 a.m. EDT, with all the samples secured in the trays, Jason headed home. Stepping out into the morning air everyone felt the tension of the recovery slip away and began to eagerly await the arrival of Jason back on the surface. Jason broke the surface and set down on the deck of the Ron Brown at 8 a.m. carrying her precious cargo. Crew and scientists gathered round eagerly waiting to see the compass. Bob was right there, too.“It was off-gassing all the way up,” he worried. “I hope it is still intact.” One look over the rim of the bucket told us the compass was fine. The clear glass face revealed the words: D. Baker Boston Nov. 3, 1874 - June 1, 1875.

Jack went to work immediately searching the Web. Along the rim are engraved the numbers "8888." Jake gently transported the instrument to a carrying container and took it to the lab, where everyone gathered round with cameras to capture the historic moment. Within the hour, Matt Heintz, the Jason expedition leader, came into the lab with an image hot from his cousin, who has been collecting genealogy data on the “Bakers” in his family. The old black-and-white photo proudly showcased the schooner Blackhawk, which had sailed out of the Naponsett River in Massachusetts and was lost in the Gulf of Mexico. The schooner bears an eerie resemblance to the remains sitting 7,000 ft below us, right down to the long slender anchors hanging from the standing rigging on the starboard side.

Grinning, Matt asked, “So do I get to keep the compass if the shipwreck once belonged to my family? It will look great on my mantle at home.”

Searching the U.S. Minerals Management Service database of shipwrecks, Rob found another Blackhawk schooner lost prior to the date of the compass patent date. One ruled out. Matt’s family Blackhawk was not lost until the 1930s (we’re thinking that is bit too late). But somewhere out there is the name of a schooner lost in the Gulf of Mexico that carried this particular Baker compass.

So, what’s next? As we steam toward our next wreck we are all furiously transcribing data and logging images so we will be ready . . . ready for the next exciting dive with Jason.