Figure 1. Researchers conducted reconnaissance aboard the NOAA research vessel Nancy Foster, in 2008. Click image for larger view and image credit.

Figure 2. The galatheoid crab, Eumunida picta, catches and consumes a squid. Click image for larger view and image credit

Reconnaissance Cruises

Ian R. MacDonald, PhD

Professor

Florida State University

Peter J. Etnoyer, PhD

Doctoral Student

Harte Research Institute

Texas A&M University – Corpus Christi

Leslie Wickes

Graduate Student

Temple University

The purpose of our reconnaissance cruises is to survey and identify sites with coral communities suitable for more detailed studies. In the past year, our research team conducted two reconnaissance cruises that provide us with information to determine study site locations. Lophelia II 2008, the first reconnaissance cruise, took place in September 2008 and used a small remotely operated vehicle (ROV) to explore potential sites. The cruise had two legs: the first focused on shipwreck sites, and the second leg focused on finding corals around natural sites. Our second reconnaissance cruise, named the Sentry Cruise, was in June 2009 and used a newly developed autonomous underwater vehicle (AUV). This essay summarizes our findings from both of the reconnaissance cruises.

As detailed in the Mission Plan, finding deep-water corals is not a simple task. Prior to the reconnaissance cruises, we analyzed seismic data for the likely presence of hardground substrates required by corals. Sometimes, however, hardgrounds are buried beneath sediments and are unavailable for coral to propagate. We can’t know this until we visit the site with an underwater vehicle, and sometimes we come up empty handed! Knowing where corals do not live also provides important information for predicting their distribution.

Lophelia II 2008

Our research team was at sea for two weeks in September 2008 aboard the NOAA research vessel (R/V) Nancy Foster with the Saab Seaeye Falcon DR ROV. We explored eight sites with the ROV, collecting specimens, video, and photo data from 250- to 500-meter (820- to 1,640-foot) depths. The dives provided valuable data on the abundance of corals in different environmental conditions and geological settings. High-resolution seafloor topography (multibeam) data were gathered at 13 sites. The maps produced from the data will guide our return trips in 2009 and 2010.

The primary purpose of this first reconnaissance cruise was to identify more coral sites in the Gulf of Mexico. Shallow sites had abundant gorgonian (soft branching) and antipatharian (black) corals, but no scleractinians (stony corals), including Lophelia pertusa. We suspect that high temperature variability in shallow water may prevent deep-water scleractinians from colonizing shallow sites, such as the Green Canyon 140 site at 200- to 300-m (656- to 984-ft) depth. At the Garden Banks 201 site, 300- to 520-m (984- to 1,706-ft) deep, thick sediments covering hard substrate may prevent coral larvae from settling and coral survival.

While exploring a long and linear ridge, a continuation of a known coral ridge feature at the Green Canyon 234 site at 300 to 520 m (984 to 1,706 ft), we found a new habitat colonized by Lophelia. However, the majority of the coral at the site was dead except for soft corals that appeared healthy. We collected a white bubblegum coral, Paragorgia sp., the first live occurrence of this genus in the Gulf of Mexico.

The most exciting discovery was at Mississippi Canyon (MC) 751 at 450- to 500-m (1,476- to 1,706-ft) depth. At this site, large carbonate outcrops were colonized by healthy thickets of Lophelia, with numerous species of gorgonians and antipatharians present. Chemosynthetic (able to create energy from inorganic compounds) tubeworms were found living at the base of the outcrops. A small, canyon-like feature at the site may channel sediment away from the area and the corals. Overall, the habitat was fairly low relief, but it was the most impressive new Lophelia site found.

The final dive at an unexplored area of Vioska Knoll (VK) 906, ranging from 380 to 410 m (1,246 to 1,345 ft), transited a long ridge system with gorgonian and antipatharian corals at the edge of a narrow, canyon-like feature. We explored a series of mounds at the southern portion of the site. One mound appeared to be composed of carbonate rubble and dead Lophelia skeletons. Live Lophelia colonies were growing from the rubble on a fairly flat seafloor. This type of Lophelia habitat has not been observed previously in the Gulf of Mexico, so it provides another good target for future exploration and research.

Several specific observations fueled new questions that researchers will pursue in the future. Among these observations was the conspicuous presence of large Leiopathes black corals on carbonate outcrops. Isotope studies of the genus Leiopathes have revealed colonies in excess of 4,000 years old. We know that Hawaiian Leiopathes colonies are the world’s oldest animals. Could the Gulf of Mexico black corals be just as old? The presence of fish and crustaceans underscores the importance of these colonies to other animals. ![]() Watch the video . . .

Watch the video . . .

The galatheoid crab, Eumunida picta, was common and conspicuous in and around coral sites. The crabs are often seen raising their claws up into the water column, waiting for food to come floating by. At one point we observed what happens when a squid floats a little too close. Snap! The crab reacts quickly, and snares its prey. ![]() Watch the video . . .

Watch the video . . .

Many types of fishes were observed, including pelagic sharks, demersal catsharks, yellowtail bass, barrel fish, and roughy. Some are commercially fished. Understanding the relationship between deep-sea coral reefs and fish habitat is an integral part of the Lophelia II: Reefs, Rigs, and Wrecks study, so researchers will continue to document these types of associations.

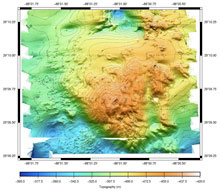

Figure 3. High-resolution bathymetry (depth measurements) of Viosca Knoll (VK) 826 will be used in combination with pictures taken by the Sentry autonomous underwater vehicle to spot areas of coral assemblages shown by the topography in the map. Click image for larger view and image credit.

In June of 2009, researchers returned to sea for the second reconnaissance cruise of the Lophelia II project. We sailed on the R/V Brooks McCall, owned and operated by TDI-Brooks, carrying Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution’s (WHOI) Sentry AUV. We collected important data at many previously unexplored sites using this unique “autonomous robot” tool. Unlike the Seaeye Falcon ROV used in the first reconnaissance cruise, the Sentry AUV is completely programmed prior to deployment and can operate underwater independently of the WHOI operations personnel. Sentry can explore sites over 4,200 m (13,779 ft) deep. On-board sensors tell the AUV exactly how high off the seafloor it’s traveling, which allows Sentry to maneuver through rugged terrain. In survey mode, the vehicle “flies” close to the seafloor, taking thousands of pictures and capturing extremely high-resolution multibeam data. When operated in ROV mode, a pilot controls the four propellers for more precise maneuvering.

The Sentry AUV collected thousands of pictures from each site. From the pictures, we spotted very interesting fish, isopods, crabs, lobsters, and plenty of sea cucumbers. The MC885 site at 620 m (2,034 ft) was one of the most active we visited, filled with tubeworms, gorgonians, and interesting topography.

We used Sentry’s precise survey mode to maximum effect during a survey of a probable nineteenth-century shipwreck. The AUV flew 20, 500-m (1,640-ft) long tracks spaced 5 m (16 ft) apart to document the wreck and associated debris field. A preliminary mosaic of the hull, created by combining numerous close-up pictures, shows the hull upright, with mast, rigging, and deck machinery clearly visible. This discovery has set the stage for follow-on archaeology — hopefully, to determine the name and origin of this wreck. See the Deep Wrecks essay for images of the mosaic.

The last site we visited was at the relatively well-studied VK826 area at about 450 m (1,476 ft). VK826 has been explored many times but using Sentry gave us the first opportunity to collect high resolution multibeam data at 1 meter resolution. The detailed images give us the ability to visualize Lophelia pertusa reef structures rather than just the typical topography of the abiotic (non-living) habitat (i.e., mounds, craters). Learning how multibeam data from this site can reveal the presence of L. pertusa reef structures will be vital in our efforts to predict coral assemblages in other unexplored sites.