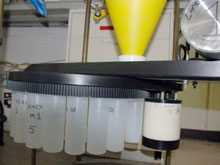

Sediment and larvae collection bottles on a rotating stage at the base of a trap. Click image for larger view and image credit.

Chris German watches the deployment of the sediment-trap mooring. Click image for larger view and image credit.

What’s Feeding These Coral Communities?

September 2, 2009

Chris German

Geochemist

Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution

![]() This slideshow shows the scientists in action.

This slideshow shows the scientists in action.

How do the deep-sea corals get to where they are, perched on narrow slivers of rock on an otherwise muddy bottom (not a great place to live if you’re a filter feeder)? Once they get there, where do the corals get the food they need to live? These are the questions that I have joined this cruise to help answer. Me, and my big yellow “buckets.”

Actually, these buckets are sophisticated instruments called sediment traps. They work more like giant funnels that are put out just above the seabed to collect material falling from overhead — both larvae and organic detritus. The larvae are the juvenile versions of the organisms we are interested in that move about through the ocean before deciding where to settle; (think teenagers going through their backpacking stage). The organic detritus "rains" down from the sunlit ocean surface. We commonly call this falling matter “marine snow”; (think supermarket traffic before a holiday weekend, or getting in line at your favorite drive-in).

Here’s how the sediment traps work: at the top end they are wide open so that they can catch all the material falling to the seafloor over an area of about 1 meter2 (3 feet2). Anything that falls into the top of the cone then slides down the smooth sloping walls of the funnel to the bottom and into a collecting bottle. Now for the clever part. Instead of having a single bottle at the bottom, the trap has 21 separate bottles on a rotating stage. At pre-determined intervals, the stage rotates, closing off the current bottle and positioning a new bottle under the funnel to collect a new sample.

Crew of the RV Ron Brown deploying sediment trap. Click image for larger view and image credit.

Crew members aboard the NOAA ship Ronald H. Brown deploy floats on sediment-trap mooring. Click image for larger view and image credit.

Time in a Bottle

Next year we plan to come back and pick up the traps from the seafloor. We will see not only what landed at each of our study-sites (how many pioneering larvae, ready to stake a claim and set up home, how much food to help sustain these coral communities) but also when. Each bottle will contain two-weeks worth of material raining down at the site. If we line them up in a series, we are likely to see patterns across time. The series of bottles may show whether these fluxes vary with the seasons, or whether they are linked to particular events in the upper ocean that we can track with satellite images — such as the Mississippi outflow or storm surges. As well as sifting through each sample for larvae, we’ll also study their chemical compositions for things like organic carbon to gauge the "food quality" of what’s raining down at each site.

Where Did That Come From?

As well as the traps and any data from the overlying ocean, we will also put out current meters on the seafloor. Like underwater weather vanes, they measure how strong the currents blow at the seabed as well as what direction they are traveling. So then if we do see anything interesting arrive in our big yellow buckets, we’ll not only know when they arrived, but also from which direction they were traveling.

To make sure we don’t collect material that has been stirred up during our program by the remotely operated vehicle (ROV) Jason, I’ve programmed the sediment traps to start work on Friday, September 11, after the last Jason dive has ended, and then to collect a new sample every two weeks through until July 2, 2010. (Not even a machine should have to work on the weekend of July 4th!) Even though the traps will be out of sight on the ocean floor for a year, they won’t be out of mind. I’ve programmed the sample change dates into my iPhone and spotted some significant alternate Fridays in the year ahead when the traps will be collecting new samples, including my wife’s birthday in October, New Year’s Day, and my Dad’s birthday in March. And because I’m British, I can’t resist pointing out my traps will be working hard on April 23 (St George’s day) — even if I do give them vacation time next July 4th!