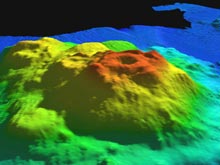

In this multibeam image of Ely Seamount, the caldera (aka the Crater of Doom) is visible at the apex of the seamount. Click image for larger view.

The (Unrealized) Adventures of Alvin and the Crater of Doom

August 23, 2004

Jeff Pollack

NOAA

Office of Ocean Exploration

DSV Alvin pilot Anthony "Tony" Tarantino skidded up to my table in the mess just as I was polishing off my second Oh Wow bar. (This delectable, chocolate-caramel-oatmeal creation inspires down-right desperation in anyone unlucky enough to have missed the dessert tray). He dropped a single sheet of paper in front of scientist G. P. Schmahl.

“We got it!” Tony said, grinning from ear to ear.

Tony, who was slated to pilot the deep submergence vehicle (DSV) Alvin during dive #4043, had just received word from Alvin expedition leader Dudley Foster: the Navy had granted us permission to explore the caldera (large volcanic depression) at the apex of Ely Seamount. Tony’s enthusiasm was contagious, and soon Tyler Fox and G. P. Schmahl -- the two science observers scheduled for the dive -- were slapping hi-fives across the table.

Ely is the smaller neighbor of Giacomini Seamount; both are thought to be about 20 million years old. The multibeam images collected by the science party aboard the R/V Atlantis show us that this caldera is about 1 km wide and 200 m deep and may be full of sediment. Because the science party had accomplished its defined objectives on Giacomini during its first three dives there, the four principal investigators decided to expand the range of our exploration in the region.

Much to the chagrin of the geologists on board, most of the science party promptly abandoned any scientifically accurate terminology and began referring to the caldera as the "Crater of Doom." By late evening, our imaginations had gotten the better of us, and we were all envisioning the Alvin boldly venturing into an uncharted abyss.

But our whimsy was short lived.

When I made my way to the bridge at 12:30 am to visit the crew on the late watch, I saw conditions weren't good. The wind was registering over 30 knots, and a white explosion of foam and sea spray enveloped the bow whenever the Atlantis met one of the larger swells.

Later, after six hours of intermittent weightlessness in my coffin-sized berth, I made my way outside, hoping the weather had changed. The gray skies were clearing overhead and beautiful orange sunbeams radiated on the horizon. A curious Northern sea lion tumbled around off the port side of the ship. Despite what seemed to be improving conditions, the wind was still hovering around the 25-knot threshold of safety for Alvin operations. I learned from pilot-in-training Gavin Eppart that the Alvin’s regular 8 am launch was on hold until nine o’clock, at which time the weather would be reevaluated.

The call officially came from the bridge just after 9 am. Everyone on board -- especially G. P. and Tyler -- was disappointed to learn that the dive had been cancelled. While the crew may have been able to launch the Alvin safely under the morning’s conditions, the captain determined that strengthening winds and building seas would have made the afternoon recovery of the sub too risky.

And so, as the R/V Atlantis steams for Astoria, Oregon and the 2004 Gulf of Alaska Exploration draws to a close, the exploration of the Crater of Doom will remain the fodder for our dinner-time discussions . . . of what could have been.

Sign up for the Ocean Explorer E-mail Update List.