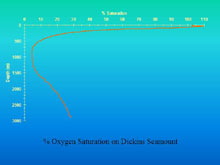

Oxygen concentration is extremely low at mid depths on seamounts. Click image for larger view.

![]() See DSV Alvin peek around a Primnoid coral to see a large aggregation of brittle stars. (mp4, 3.2 MB)

See DSV Alvin peek around a Primnoid coral to see a large aggregation of brittle stars. (mp4, 3.2 MB)

A Paradox of Seamounts

August 17, 2004

Dr. Thomas C. Shirley

University of Alaska, Fairbanks

Marine scientists who observe the high densities and diversity of life forms on seamounts are often surprised to learn that the oxygen content of water around seamounts is extremely low. Seamounts often are bathed by waters containing less than 5% of the oxygen found in surface waters. How can this be so? What causes the oxygen-minimum zones (OMZs), and how do the animals cope with this oxygen stress? Having OMZs in cold waters almost seems counterintuitive as most cold waters have high oxygen content.

Surface oceanic waters (the upper several hundred meters) are well oxygenated as a result of several processes. Photosynthesis by phytoplankton produces oxygen. Perhaps more important, however, is the diffusion of oxygen from the atmosphere into surface water, followed by rapid surface circulation from currents and wave action. No photosynthesis occurs at depth because of the lack of light, so all oxygen at depths below the photic zone (zone of light penetration) is derived from surface processes.

The decline of oxygen in the deeper waters is caused by biological or chemical oxygen demand and the lack of re-supply from shallow waters. Dense spring phytoplankton blooms sink below the photic zone and begin respiring more oxygen than they produce, finally robbing the water of oxygen by decay and chemical oxidation. When a surface layer of water "caps" the deeper water, thereby inhibiting circulation and exchange between the water masses, the stage for OMZ is set. The decrease in exchange between the water masses is often caused by strong thermoclines (zones of rapidly changing temperature) or haloclines (zones of rapidly changing salinity), or some combination of the two, resulting in strong density gradients between the two water masses.

Seasonal OMZs are common over the shallow continental shelves of some oceans. The "dead zones"of the near shore Gulf of Mexico are good examples of seasonal OMZs, where the influx of high nutrient-laden water from the Mississippi River ultimately depletes the receiving seawater of its oxygen, resulting in hypoxic events. Also, OMZs on seamounts in tropical and subtropical areas have been investigated; but few people associate the cold, salmon and crab-rich, subarctic waters of Alaska with OMZs.

Acanthomastus (a soft coral) is one of many corals thriving in waters with low oxygen. Click image for larger view.

How can life flourish in OMZs on seamounts? The predominant fauna in OMZs are passive suspension feeders: sedentary organisms that rely on the currents around seamounts to bring food to them. As a result, the sedentary fauna (e.g., corals, brittle stars, crinoids, anemones) have low metabolic rates. Some of these animals have other metabolic tricks. For instance, brittle stars and many corals have low tissue mass, as much of their body is composed of inert calcareous skeleton; many animals save energy by being sessile. We know that many other members of the seamount fauna restrict their activities to short bursts; some are even capable of anaerobic (without oxygen) metabolism. Others are thought to employ special respiratory pigments or have enlarged respiratory structures and chambers. Some organisms have specialized appendages to increase water flow over gills.

The low oxygen content in the water above seamounts limits the amount of zooplankton that can live in the water column. As a result, much of the food from shallow waters arrives on the seamount relatively unconsumed. The seamounts intercept ocean currents and internal waves of tides, creating eddies that retain this abundant food around the seamounts.

The gradient in oxygen concentration results in strong biotic zonation. Predators having higher metabolic demands are excluded from the zones of lowest oxygen on the seamounts, so these low-oxygen zones serve as refuges from predation for sessile or slow-moving consumers. In well-oxygenated zones, predators limit the distribution of these vulnerable slow-moving organisms. On seamounts, oxygen may be the key environmental factor that determines animal distribution and limits their abundance and diversity.

Sign up for the Ocean Explorer E-mail Update List.