Catalina Martinez enters the DSV Alvin for her first dive, while Alvin pilot-in-training Mark Spear prepares the sub for launch. Click image for larger view.

At Long Last . . .

August 5, 2004

Catalina Martinez

NOAA

Ocean Explorer Expedition Coordinator

From birth, Man carries the weight of gravity on his shoulders. He is bolted to Earth. But Man has only to sink beneath the surface and he is free. Buoyed by water, he can fly in any direction . . . up, down, sideways. Underwater, Man becomes Archangel. -- Jacques Cousteau

Or "Woman," that is . . .

![]() View a video of Antipatharian, or black coral, in 1,400 m of water on Denson Seamount. (mp4, 2.1 MB)

View a video of Antipatharian, or black coral, in 1,400 m of water on Denson Seamount. (mp4, 2.1 MB)

Through my work with NOAA, I’ve been fortunate to have witnessed between 30 and 40 deep submergence vehicle (DSV) Alvin dives on the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution R/V Atlantis. I have never missed a launch or a recovery, but I have dreamed of the day I would experience a dive through my own eyes, rather than through the detailed storytelling of others. It is an incredibly impressive operation, and getting a dive in the DSV Alvin remains the ultimate experience for many marine scientists -- including myself.

Today, I am one of the fortunate few to join the ranks of those who have had this experience. I dove -- in Alvin -- to 2,480 m on Denson Seamount, with chief pilot Bruce Strickrott at the controls and Oregon State University graduate student Jason Chaytor (also a first time diver) as port observer. It was Alvin dive #4,027.

The experience was so much more than I had imagined!

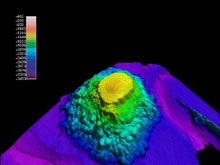

I was inside the titanium sphere. Our rocky ride at the surface transitioned to stillness for the glide to the targeted dive site -- the southern flank of the seamount. There were long colonies of salps (gelatinous colonial organisms) in the water column, and as we entered the darker depths, we were engulfed in an amazing display of bioluminescence! We selected our targeted dive site in the wee hours of the morning by looking at bathymetric maps made from the multibeam data acquired just hours before. Scientists decide where to send Alvin based on previously determined objectives as well as the specific topography and depth they believe will help achieve these objectives.

A multibeam image of Denson Seamount, looking roughly to the northwest. Our dive target was on the southeastern flank. The sea channel on the right is about 3,200 m deep. Click image for larger view.

Jason Chaytor shines a flashlight out the porthole to assist Alvin pilot Bruce Strickrott with basalt rock selection. Click image for larger view.

We touched down in a cloud of sediment, and I immediately saw several bright red shrimp swim past my seven-inch diameter porthole. Once the sediment cleared we knew we were in a good location: the sub was surrounded by large basalt (volcanic) rocks. The primary objective of the dive was to collect these ancient boulders. Jason and Bruce determined which rocks were more likely basalt (and, thus, actually associated with the seamount) and which might be imposters – called erratics. Making this determination is not usually an easy task, but in this location we could see the clear indications of basalt fracturing. Jason and Bruce were pretty confident in their collections.

I've watched hours upon hours of dive video from many different cruises over the years, but I was completely amazed by the three-dimensional world I saw through my porthole. Clearly, nothing compares to "being there." Although our landing site was sparse with biology, I was amazed by the diversity of organisms I could see right by my porthole. There were several long transparent sea cucumbers with strange appendages and suction-cup feet! There were more familiar critters as well, such as brittle stars, sea stars, stalked crinoids, stalked sponges, tiny corals, and a few rattail fish. Even a large ray decided to pay us a visit.

Alvin pilot Bruce Strickrott photographed this lovely meter-tall stalked sponge through submersible's porthole. Notice the tiny shrimp. Click image for larger view.

At one point, a strong current caused some difficulties with the port manipulator. I was impressed by our pilot Bruce's ability to change strategies. I watched as he tried to collect samples with a more rudimentary arm, position and focus cameras, and maintain Alvin’s position all at the same time. He was multi-tasking like crazy; and, as observers, Jason and I could do nothing but watch. (Now I understand where our title -- "observer" -- comes from!) It was a bit frustrating, knowing that I couldn’t be of assistance, but it was really all up to him. Alvin pilots have amazingly difficult, but very exciting, jobs.

We had scheduled a satellite phone call to the Urban Collaborative Accelerated Program (UCAP) school in Providence ![]() , RI to take place during our dive. The call went very well. Several of the scientists were in Top Lab for the phone call, and Carey DeLauder, our Educator at Sea, who is a science teacher at UCAP, hosted the call with Alvin expedition leader Dudley Foster. Patrick Neumann, former UCAP student and new OS (ordinary seaman) on board the Atlantis also participated in the call. (His presence on the ship is an amazing coincidence!) We were able to answer a few questions from students and teachers, and the scientists in Top Lab continued the call when those of us in the sub signed off.

, RI to take place during our dive. The call went very well. Several of the scientists were in Top Lab for the phone call, and Carey DeLauder, our Educator at Sea, who is a science teacher at UCAP, hosted the call with Alvin expedition leader Dudley Foster. Patrick Neumann, former UCAP student and new OS (ordinary seaman) on board the Atlantis also participated in the call. (His presence on the ship is an amazing coincidence!) We were able to answer a few questions from students and teachers, and the scientists in Top Lab continued the call when those of us in the sub signed off.

(Left to right) Catalina Martinez, Kevin Penn, and Shinobu Okanu, enjoy a spectacular sunset and rainbow that lasted late into the evening. This picture was taken at about 10 pm. Click image for larger view.

During our dive we drove up a few steep ledges and collected several rocks, as well as coral, sponge, and other invertebrate specimens under difficult conditions. When our time at the bottom came to an end, Bruce let me release the lead weights from Alvin, and immediately we left the bottom for our long journey to the surface.

No first dive would be complete without a proper "initiation." Back on board the Atlantis, the scientists, and crew lined the upper and lower decks, waiting to dump buckets of ice water on us and to pelt me with water balloons! That night, as several of us enjoyed the spectacular sunset at about 10 pm, we realized we were looking at a double rainbow as well. It was a phenomenal ending to one of the most special days of my life.

The UCAP Connection

Catalina Martinez

NOAA

OE Expedition Coordinator

My path to a career in ocean science was not direct, and certainly not traditional, as I spent many years working in human service before studying oceanography. For five of those years, I worked at an alternative middle school called UCAP in Providence, RI.

Although Providence is the capital of the "Ocean State," the city’s school children did not have much exposure, if any, to the marine environment at the time I was growing up or during the years I worked at UCAP. So, once I was able to attend college full-time, I knew I wanted to learn as much as I could about this mysterious environment. I wanted to understand all the weird and wonderful creatures that existed because of it.

While I was in graduate school at University of Rhode Island (URI), I received a National Science Foundation Graduate Teaching Fellowship. It allowed me to go back to UCAP to work with the students and science teachers to incorporate marine/environmental science into their curriculum. We developed field programs to get the kids "wet." We even brought them out on URI’s small research vessel, the Cap’n Bert for oceanography programs that included fish trawls, sediment work, and water chemistry.

Now, here I am, several years later, working for NOAA as a marine scientist, and I am in the unique position of providing opportunities to educators and students to participate in exciting research cruises. The students get to participate indirectly through ship tours and classroom visits, email, satellite phone calls, and Web entries. A few fortunate teachers join the scientists at sea.

When I realized we had a space available on this cruise for an educator, I contacted Carey DeLauder, one of the UCAP science teachers, and invited her to participate. She eagerly accepted, and we started to plan how we could incorporate her experiences into the upcoming school year. We also thought about how we could get the kids involved while we were at sea. We planned several satellite phone calls from the ship, and Carey plans to work with UCAP science teacher, Maureen Farrell, to use the NOAA Ocean Explorer curriculum during the first quarter of the school year.

During our second day at sea, one of the new Atlantis crew members, Patrick Neumann, approached me and asked if I worked at UCAP 10 years ago! I was stunned. Here was a former UCAP student, now working on board one of the largest and most significant oceanographic research vessels in the U.S., on a cruise in which Carey is participating -- and I am the coordinator!

We took immediate advantage of this "UCAP connection" and had Patrick join in on the first satellite phone call to UCAP on August 3. I was in the sub, while Carey and Patrick were in Top Lab, hosting the call with a group of the scientists on board. Together, the scientists answered a whole host of questions, and Patrick spoke frankly with the students about making choices in their lives. He implored them to stay in school and to pursue something they love in life. We will host another satellite call to the UCAP students on Friday, August 6.

Sign up for the Ocean Explorer E-mail Update List.