A zoomed-in view of Paragorgia with polyps extended. Click image for larger view.

View a slide show of some of the deep-sea corals of the Alaska Seamounts. ![]() Click image to view the slide show.

Click image to view the slide show.

Follow That Sample! The Saga of How a Deep-sea Coral Is Processed

August 16, 2004

Amy R. Baco-Taylor, PhD

Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution

![]() Coral and other biological samples are taken into the cold room for processing. (mp4, 10.6 MB)

Coral and other biological samples are taken into the cold room for processing. (mp4, 10.6 MB)

DSV Alvin dive #4028: We are the first people ever to set eyes on Dickens Seamount and its fauna. We landed on a pinnacle, just south of our intended ridge dive site. The basalt (volcanic rock) is covered in large sponges of all shapes and sizes. Cone-shaped with fluted edges is the most abundant growth form for the sponges here; and they come in a variety of colors -- white, yellow, and peach. Like corals, sponges are suspension feeders and prefer to live in areas of high current flow.

Amidst all these sponges, we spy our first coral: a bright red Paragorgia, or bubblegum coral, as seen in the images and video. This species is frequently brought up tangled in fishermen’s trawls and long lines throughout Alaska.

On this cruise, there are several groups working together to study the corals and the communities that use them as habitat. There are several steps we follow to process every coral sample we collect in order to make sure everyone gets the data they need.

First, before we touch it, the coral is photographed and videotaped extensively (Slideshow images 1-2). We zoom in with the camera to get a good look at the polyps and any critters that are crawling around on the branches. This Paragorgia had a large number of shrimp "sitting" on it.

Once the photo documentation is complete, we get out the large “slurp gun” -- a kind of underwater vacuum cleaner that has rotating storage chambers so we can keep individual samples isolated from each other (Slideshow image 3). We use the slurp gun to pull all the critters off the coral colony, especially those that would jump off or swim away when we try to collect the coral.

Next, we engage the manipulator arm and collect the coral by snapping it off near the base. The coral is then placed in a biobox, an insulated container that keeps the samples cold and holds them in water until we take them off the sub on deck (Slideshow image 4). We close the biobox and then move on to our next sampling site.

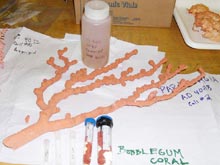

The collection of tubes and jars from the processed Paragorgia colony The large piece is the dried sample that will be sent to the Smithsonian Institution. Click image for larger view.

At the completion of the dive, we remove all of the bioboxes from the sub and take them to the cold room. These corals live in very cold water, only a few degrees above freezing. We want to keep them alive as long as possible; by working in the cold room, we are able to keep the water in the biobox cold and the corals happy.

Opportunities to sample deep-sea critters are rare, so the samples we get are very valuable. We want to preserve them for as many different types of analyses as we can. Even if we don’t plan on doing certain analyses, someone from another lab may be interested later on and need to borrow samples from us. So after photographing the colony, we preserve each coral at least seven ways.

First, a small piece of coral that will be used for DNA analysis is placed in a cryogenic tube and frozen at -80º C. Another piece, which will be used for taxonomic identification and for supplemental DNA work, is cut off and preserved in 95% concentration of alcohol. Yet another piece is taken to examine what the corals may have been eating, and we also preserve a sample in formaldehyde for future reproductive studies. A final sample is taken and preserved for RNA studies.

Some corals are very mucousy. There are unique bacteria associated with mucus, so we also scrape mucus off for microbial studies. If there are any critters still attached to the corals, we also preserve those organisms separately. What remains of the colony is preserved in ethanol or dried and will be given to the Smithsonian Institution. Researchers use dried colonies to look at branching patterns and other morphological characters for species identification.

Sign up for the Ocean Explorer E-mail Update List.