View of live Metallogorgia melanotrichos polyp with gonads. Click image for larger view and image credit.

An unidentified sea pen shares a pit with a shrimp. Sea pens (Pennatulacea) are soft-bodied octocorals that anchor into sediments by inflating the base of a large polyp with water. The side branches of this large polyp hold 10 or more feeding polyps. The surrounding sediment contains many petropod shells. Pteropods are a kind of snail that swims in the water column, and when they die their shells sink to the bottom.

![]() Click image to view a slide show.

Click image to view a slide show.

The birds do it, the bees do it, the corals do it

August 12, 2005

Anne Simpson

Graduate Student

University of Maine - Darling Marine Center

With every bounce and roll of the ship we draw closer to our first dive location, a cluster of undersea mountains known only as 'Corner Rise'. These seamounts are so remote and unexplored that individual peaks have yet to be officially named. Several days and a few hundred miles now separate us from the beautiful Azorean town of Ponta Delgada, where we boarded the ship.

We are making great time on the first leg of our trans-Atlantic journey. Word has just come from the bridge that the ship will arrive much earlier than expected at Corner Rise. This is welcome news to Dr. Allen Gontz, a geologist and geophyscist from UMass Boston. Dr. Gontz works on transforming the massive amount of data generated by the ship multibeam mapping system into bathymetric maps. These maps are essential to all the science operations on this cruise because ROV dive locations are chosen based on topographic information contained in the maps.

Many, many meetings have taken place on the ship over the last few days. These meetings are a necessary but not-so glamorous part of any research cruise. Its takes an incredible amount of coordination and communication between the ship's crew, the ROV team, and the many scientists on board to ensure a successful expedition. All the scientists met earlier today to talk about what types of specimens each person needs and how different things should be collected. During each ROV dive an attempt is made to meet the collection and data gathering needs of as many scientists as possible. As a graduate student studying reproduction in deep-water octocorals, my goal is to collect tissue from numerous corals species, especially those in the Family Chrysogorgiidae.

Colony of Metallogorgia melanotrichos on New England Seamount Chain. Click image for larger view and image credit.

Studying reproduction in deep-sea animals, like octocorals, can be challenging. The Deep Atlantic Stepping Stones cruise is the only chance I will have this year to collect coral tissues and examine their reproductive structures. These coral tissues will provide only a 'snapshot' of the entire reproductive cycle which may take from months to years to complete. Ideally, I would collect coral tissue samples every few weeks over the course of a year or more to document the full reproductive cycle, a common practice for reproductive studies in shallow-water corals. Such frequent collections of deep-water coral are, of course, impossible because the environment where these animals live is so difficult for humans to access. For that reason, I consider myself fortunate to have samples even once a year.

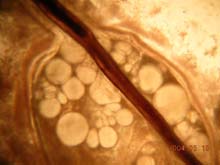

Histological section of Metallogorgia melanotrichos polyp with developing eggs (oocytes). Click image for larger view and image credit.

Even a 'snapshot' of the reproductive cycle can provide a lot of information about the process of reproduction in deep-water corals. For example, studies of Metallogorgia melanotrichos tissues collected during the Mountains in the Sea Expedition in May 2004 have revealed that colonies are separate sexes. Female corals produce eggs inside their polyps. A single polyp may contain up to 34 eggs (in different stages of development) at any one time. Eggs form in clusters along the mesenteries. As the eggs grow they fill with yolk-like granules, eventually detaching from the mesentarial wall. Fully mature eggs sit at the top or bottom of the gastrovascular cavity. In male colonies, developing sperm sacs are found inside polyps attached to mesenteries. Although sperm sacs vary in size, the developing spermatocytes enclosed in the sacs appear to be developing synchronously. This suggests that Metallogorgia melanotrichos may spawn in a single event or over a short period of time.

Many questions have yet to be answered about the process of reproduction in just this single species of deep-water coral. The Deep Atlantic Stepping Stones Expedition will provide another valuable 'snapshot' which will doubtlessly further our knowledge of reproduction in deep-water corals.

Sign up for the Ocean Explorer E-mail Update List.