Discarded fishing gear caught on Solenosmillia and Lophelia pertusa scleractinian corals. Click image for larger view.

Fisheries Impacts on Deep-Water Corals

Rhian Waller

Postdoctoral Fellow

Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution

Go down to your local fish shop and you are now likely to see orange roughy and grenadier packed next to the cod, mackerel and lobsters, yet these species live much deeper than those caught at the more traditional fishing grounds. With the rapid decline of commercially important pelagic fish species, many fishing trawlers are having to explore deeper realms to maintain the fish catches needed to keep them in business.

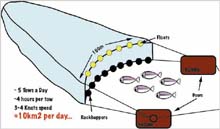

Yet, as research is now finding, many of these deeper-dwelling species live around the same fragile coral ecosystems this cruise is set to explore. Deep-water corals have been estimated to harbor more then 1000 different species of invertebrates and fish, with the corals themselves providing a safe habitat to feed and reproduce. Yet fishermen have known for years that these coral areas attract many marketable fish. They had traditionally been avoided as fishing grounds because of the expensive damage the coral mounds caused to nets and gear. However, with developments in equipment, such as 'tangle nets' and 'rockhoppers' (large balls or rollers developed to smash rocks and corals that might break the nets) more fishermen are able to fish these areas without losing or damaging their gear.

But what impact are trawlers having on deep-water corals?

Orange Roughy, one of the most commercially fished deep-water species. Orange Roughy can live for around 150 years and do not begin to breed until they are around 25 years old, making them extremely susceptible to over-fishing. Click image for larger view.

Seamounts in the New England Seamount Chain have in the past been commercially trawled (with Bear being the most frequented), as have many other deep-water coral areas across the globe. A single deep-sea trawler in the North Atlantic generally trawls a 100m wide net for around 20 hours a day, covering a distance of around 10 km. During this time any benthic fauna within the trawl path is being scooped up into the net, or crushed by rockhoppers. With some deep-sea octocorals being estimated to live for thousands of years, and colonization known to be very slow, removal of these corals through trawling is a huge loss to the ecosystem, taking many years to recover.

Trawlers can have an effect on deep-sea corals in a number of ways. The first most obvious is the destruction of the coral itself, if not being scooped up in to the net, then being broken by the heavy fishing gear. Once a hard coral has been broken into many pieces they are very often still alive, however if their new position isn't as suitable (e.g. not enough current or to much sediment), the coral will soon die. An octocoral on the other hand will most likely die quickly if knocked from its original position. Another affect trawlers can have on corals (and other deep-sea species) is the re-suspension of sediment from the heavy gear on the seafloor. Sediment suffocates the polyps of corals, making them unable to feed, excrete or respire, thus increased sedimentation will cause polyp or colony death. The stress that ensues following either of these types of event can also have a negative effect on the corals ecology. Studies have found that many shallow water scleractinians stop reproducing if damaged, saving the energy they need to re-grow the broken parts, and it is thought this may be the same with deep-water corals.

Illustration of a deep-water trawl net. These nets have large heavy doors to keep the net open on the bottom, along with rockhoppers these heavy weights can crush corals and other benthic fauna. Click image for larger view.

Because there are still so many gaps in our knowledge of these corals' ecology we really do not know the full damage these fishing practices have had, and are having, on coral ecosystems. In some areas deep-water fishing still occurs, yet there are measures to protect these fragile deep-water coral areas. A number of deep-water coral areas have been designated as Marine Protected Areas (MPA's), hopefully preventing fishing and other anthropogenic impacts to deep-water corals, allowing scientists to study and better understand these beautiful and unique organisms.