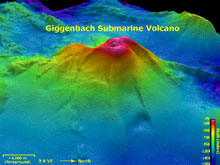

Giggenbach submarine volcano viewed from the east looking west. Depths range from 75 to 1600 meters (246 - 5250 feet) in this image. The resolution of the bathymetry data is 25 meters. The image is two times vertically exaggerated. Giggenbach is ~30 kilometers northwest of the center of Macauley caldera. The bathymetry data are courtesy of New Zealand National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research (NIWA). Click image for larger view.

First Dive On Giggenbach Volcano

April 18, 2005

Matt Stott

Microbiologist

Institute of Geological & Nuclear Sciences

Wairakei, New Zealand

![]() Hydrothermal

vents found at Giggenbach volcano are releasing streams of bubbles. (Quicktime,

1.8 Mb.)

Hydrothermal

vents found at Giggenbach volcano are releasing streams of bubbles. (Quicktime,

1.8 Mb.)

![]() Giggenbach

volcano gas bubbles sampling. (Quicktime, 1.9 Mb.)

Giggenbach

volcano gas bubbles sampling. (Quicktime, 1.9 Mb.)

![]() The

Giant grouper fish of the Giggenbach volcano. (Quicktime, 1.7 Mb.)

The

Giant grouper fish of the Giggenbach volcano. (Quicktime, 1.7 Mb.)

So what is it like to be an explorer … to go where no one has ever been before? As a scientist, I had never expected to be given such an opportunity. And yet, here I was with Terry Kerby and Max Cremer standing on the back deck of the R/V Ka'imikai-o-Kanaloa and about to dive on Giggenbach, an undersea volcano only recently discovered, let alone explored. This would also be my maiden submersible dive, and so for more reasons than one, I had no idea what to expect. What would it be like? What would I be able to see out those impossibly small windows? Would we find hydrothermal vents? Would the cockpit make those groaning noises we hear on all those Hollywood movies?

Giggenbach volcano was named after the late Dr. Werner Giggenbach, a slightly excentric and energetic pre-eminent gas chemist who studied volcanoes along subducting tectonic plates. As I was soon to find out, Giggenbach volcano is a pretty amazing place, and Dr. Giggenbach no doubt would have been impressed.

As a microbiologist, I am interested in the microorganisms that live in these extreme environments in and around the hydrothermal vents, especially the ones that live at temperatures above 70°C (>158°F). These microorganisms not only survive, but actively grow at these high temperatures. It has even been reported that several strains of microorganisms can grow at temperatures greater than 110°C (>230°F). At some point during this expedition, and maybe even during this dive, I hoped I was going to find evidence of similar unusual microorganisms.

I was pleased to note that there were no groaning noises made by the submarine as we descended and as I looked out the tiny port window, the ocean floor spread out in front of me. We landed upon a sandy surface occasionally strewn with rocks that had been ejected from a previous eruption, a sure sign of Giggenbach volcano's eruptive past. A soft ambient light from the surface faintly illuminated fish, corals and rock with a slight aquamarine tinge, as the summit is less that 100 m (~325 feet) below the breaking waves.

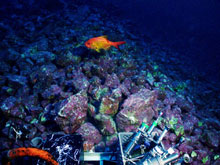

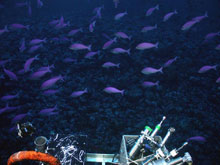

Giggenbach volcano is quite a varied environment; it has dozens of pits and craters amongst volcanic ash and altered rock, along with a classic volcanic cone made up of perfectly piled black rocks. All around the central cone, the sea life grew; urchins, shark, soft corals, schools of mau mau, kingfish, groupers (two of which followed us around for hours) and twineyes swam above volcanic rock covered with purples and pinks of algal mats. At the peak of the seamount (~70 m below the surface), wave surges pushed the Pisces V around, preventing us from enjoying the abundance of sea life swimming around in the sunlight. Instead, we concentrated on exploring pits and craters that pock-marked the lower flanks of Giggenbach ... curious groupers in tow.

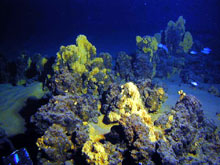

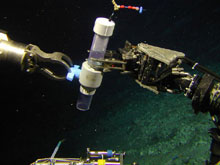

Nearing the end of the dive we had discovered several small hydrothermal vents, mats of bacteria, old chimneys, and we found out that groupers are gregarious attention seekers. We visited one last crater before calling it a day. This turned out to be a great decision because we soon found a moderate sized diffuse vent field that fed thousands of mussels covered in thick white stringy bacterial mat that waved surreally in the warm fluids that passed over them. Then, with less than an hour to go, we found the vent field that we'd all been hoping for. In front of us was a huge white wall with half-a-dozen vents streaming hot water and streams of bubbles into the ocean. The temperature of this vent was 203°C (almost 400°F) at a depth of 164 meters. That temperature is at the boiling point for seawater at that depth, which explains why we saw all the bubbles coming out with the hot water. And yet, right next to the boiling fluids were dozens of small crabs and what looked like microbial mats. Jackpot.

Leaving the bottom was hard to do. Right at the end of the dive we had found fantastic vents, with great geology and associated biology. Nevertheless, we also needed to get to the surface and begin to process our samples. Back on deck, the dive seemed surreal; it went so fast and was so exciting that I had trouble putting together a coherent sentence. However, one thing I knew for sure … I can't wait until my next dive (sorry Mum)!

Sign up for the Ocean Explorer E-mail Update List.