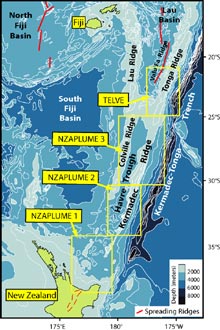

Map of the Earth indicating boundaries, mostly the midocean ridges, where plates separate (green), and boundaries where plates converge (heavy red, blue, and black lines). The Kermadec-Tonga Arc is one of the longest interoceanic arcs on the planet. Submarine Ring of Fire cruises in 2003 and 2004 visited the Mariana Arc. Click image for larger view and more details.

Exploring for Hydrothermal Systems Along a Submarine

Volcanic Arc

Edward T. Baker

Supervisory Oceanographer

NOAA Vents Program

Submarine Volcanic Arcs

Volcanic arcs are curved chains of volcanoes separated from the adjoining ocean basin by a deep submarine trench. They mark boundaries where the Earth's tectonic plates are consumed by sinking, just as midocean ridges mark boundaries where plates are created. Arcs are also the surface expression of new magma formed by the plate sinking, as this hot magma rises and forms volcanoes. A good example of this process is Mt. St. Helens in Washington State, where recent eruptions remind us that this volcanic activity is a powerful force. The Kermadec-Tonga Arc is an intraoceanic arc, one that has oceanic crust on either side, in which case the volcanoes are mainly submarine. There are almost 22,000 kilometers (~12,000 miles) of volcanic arcs along the ocean floor, almost all in the western Pacific Ocean.

Several cruises over the past six years have carefully studied

more than 100 submarine volcanoes, more than 40 of which have been hydrothermal

active. At these volcanoes, cold seawater is heated by the cooling magma

within and beneath them, becomes buoyant, and rises to the volcano summit.

The hot fluid rises like a hot-air balloon into the cold ocean, cooling

as it mixes with the cold seawater. Mixing continuously dilutes the hot

discharge and increases its volume as it rises, until the hydrothermal

plume achieves neutral buoyancy and is dispersed by the local currents.

This hydrothermal circulation pattern occurs wherever seafloor cracks can

channel seawater to layers of hot rock.

The Tonga-Kermadec Arc

The Tonga-Kermadec Arc is part of the Pacific “Submarine

Ring of Fire,” marking the location where the Pacific Plate sinks

beneath the Australian Plate. The arc stretches for some 2500 km from New

Zealand to Samoa, and is thought to include over 100 submarine volcanoes.

Four cruises since 1999 have systematically studied these volcanoes for

hydrothermal sophisticated instrument package that can detect even the

slightest “scent” of a hydrothermal plume. If hydrothermal indicators

are found, further surveys are conducted to try and pinpoint the location

of the fluid sources on the volcano. These surveys are used to guide the

later seafloor studies, such as the PISCES submersible dives to be conducted

this year.

A closeup of the primary tool used to map hydrothermal plumes. A ring of plastic sampling bottles surrounds the CTD, an electronic package that monitors seawater Conductivity, Temperature, and Depth. The bottles are closed on command from the ship, usually when a scientist monitoring the sensors sees strong evidence of a plume. The CTD carries other sensors that measure optical light backscattering, seawater pH and Eh, and other chemical species. Pictured here are Ed Baker (left) and Cornel deRonde (right). Click image for larger view and more details.

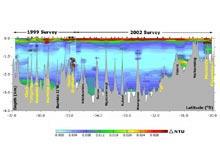

Conducting a series of cruises along the arc allows scientists

to piece together a view of the distribution of hydrothermal activity on

the arc. Results of the 1999 (NZAPLUME 1) and 2002 (NZAPLUME 2) cruises

along the southern Kermadec-Tonga arc, for example, found hydrothermal

plumes over at least 17 submarine volcanoes. Because of the different water

depths of the volcano summits, injection of hydrothermal material may occur

anywhere from 1800 meters (~1 nautical mile) to <100 meters (~325 feet)

deep. Hydrothermal fluids discharged directly into the shallow, photosynthetically

active layer of the ocean might fertilize plankton growth, increasing the

ocean productivity at those sites.

Cross-section along the southern Kermadec-Tonga Arc. Each peak is a separate volcano, formed by magma generated by heating the Pacific Plate as it sinks into the Earth below the arc. This same effect creates terrestrial volcano chains, such as the Cascades and the Andes. This plot illustrates the distribution of hydrothermal plumes by plotting the relative concentration of very fine-grained particles... Click image for larger view and more details.

Exploring the Ocean, Expanding Our Knowledge

Hydrothermal venting can develop on only a minuscule portion of the seafloor, yet its effects influence the entire ocean and support a unique biological community that may be Earth's earliest ecological niche. While we understand many of the basic principles that govern this phenomenon, we remain deeply in the explorative stage of this research. We are surprised almost daily by discoveries of vents where we expected none, chemical compositions that were unpredicted, and the cataloging of new biological species. The ocean is a harsh and unyielding environment, and new progress is hard won. But the excitement and value of increasing our knowledge of one of Earth's basic processes makes this exploration among the most rewarding we can imagine.

Many of the submarine volcanoes in the Kermadec Arc are large calderas. Calderas are huge craters that are created when so much material is expelled from a volcano during a large explosive eruption that the top of the volcano collapses back on itself. Crater Lake in Oregon is an example of a volcanic caldera on land that formed during a huge eruption about 7000 years ago. Thus the existence of large submarine calderas in the Kermadec Arc is clear evidence that these volcanoes have a very violent past.