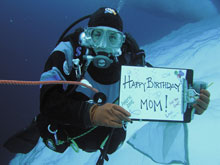

Ice diver Shawn Harper “stands” on the ice ceiling above him. Ice diving on this cruise is different from other types of diving as work is conducted on the ice close to the surface while thousands of meters of blue water unfold below. Click image for larger view.

An Upside-Down World

July 24, 2005

Elizabeth Calvert

Ice Diver

I sit on the edge of an ice floe, my feet dangling through a hole just large enough for two divers to fit through. I am bundled in layers of thermal underwear beneath my dry suit and with dry gloves on, my head is the only part of my body that will directly feel the 30-degree water. A camera is clipped in on my right side, a collection bag clipped to my left, and a 5-foot tether connects me to my buddy. A second tether clipped to my dive buddy connects us to our dive tender at the surface. As the only member of the science dive team without previous ice diving experience, I rely on my research diving experiences in other cold water environments to prepare me. And while technically I am up for the task, nothing could prepare me for the absolute beauty and orientation of the under ice world!

We use standard sampling tools for underwater research (a quadrat, goodie bag, slates, and cameras), but make a few modifications for the environment. The quadrat we will use for research now has floats attached to it, whereas at most other dive sites we would want the quadrat to sink to the seafloor where we would work. Here, under the Arctic ice, 3800 meters of blue water unfolds below us and if we drop anything (even expensive cameras) there’s no going down to get it.

Photos taken underneath the ice surface show both the complexity of the ice structure as well as the stunning shades of blue. When ice floes push together, they form pressure ridges that are visible both above and below the surface forming a complex habitat that supports an abundant and diverse assemblage of organisms.

![]() Click here to view a slide show.

Click here to view a slide show.

Ice diving is uniquely different compared to other dive operations. Sea ice can be several meters thick and forms a “ceiling” above you at all times. In an emergency, you cannot come directly to the surface for air. Understanding this, I wondered if I would be nervous underwater. Would I feel claustrophobic? Line signals are our only form of communication from under the ice to the surface. One pull means “o.k.” Two pulls means “give me more slack in the line.” Three pulls means “take up slack in the line.” And a lot of pulls means “pull me out!” It was this last one that gave me pause.

Sinking below the surface for my first dive, I was immediately struck by the beauty of the under ice habitat. Pressure ridges, formed when two ice floes push together, cause ice to be pushed both above and below the surface forming visible ridges across the ice landscape. These pressure ridges form a complex habitat beneath the surface where organisms, such as amphipods and Arctic cod, seek refuge. And with visibility reaching hundreds of feet, there is no feeling of claustrophobia. The sun shines through our entry hole, letting streams of light penetrate through the water and reach deep into the sea.

When the sun shines at the surface, I warm up quickly once I am out of the cold water. But it snows in the Arctic, even during summer months, and cold windy days make it extra challenging to gear up for a dive. I hesitate today, shivering even before I get in the water. But as I break through the thin frozen layer of water at the surface, I think to myself: I am one of only three people who will experience the underside of this ice ridge. And with that, I gear up and hop in.

Sign up for the Ocean Explorer E-mail Update List.