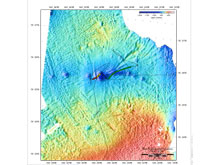

A multibeam map of the seafloor shows deep depressions, or pockmarks, in dark blue. Footage and images gathered by the ROV and photoplatform showed an unusually high density of life at the pockmark sites. The dotted line shows the Healy’s track, the green line shows the area covered by the ROV, and the red line shows the track of the photoplatform. Click image for larger view.

Fertile Findings at an Unusual Site

July 20 , 2005

Ian MacDonald

Professor of Environmental Science

Many scientific projects are occurring simultaneously on our current Arctic cruise, including different types of exploration. All of the sites visited during our 30-day cruise have been where research harbors the possibility of finding new life forms and gaining an understanding of poorly known ecosystems. Of the 14 sites sampled during our cruise track, one had the potential for unexpected discovery: site 12.

East of the Canada Basin and approaching the Northwind Abyssal Plain, site 12 was to be our Northern-most station and had been positioned to explore a series of deep depressions, called pockmarks, detected by an earlier expedition with HEALY. Most of the deep seafloor is flat and level. Even steep slopes tend to be quite level on their surface. Deep depressions signal active geologic processes—some of which can have biological significance. For example, in the Gulf of Mexico, pockmarks are often caused by gas or fluid eruptions and the chemical enrichment provided by these processes can support dense communities of chemosynthetic organisms.

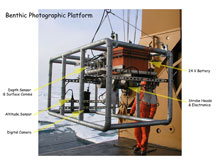

The Photographic Platform was one of three tools send down to explore the pockmarks on the ocean floor. 820 bottom photos were taken by the photo-platform showing an unusually high density of life. Click image for larger view.

Were the pockmarks around station 12 caused by gas seeps? Would we find ice-like gas hydrates and chemosynthetic life? To find out, we had to get there and station 12 was a long way from our final destination. The team on board was tight for time, but support to go look for life at the pockmark sites remained quite strong. Even when Healy encountered heavy ice, slowing our progress, the team remained committed. We ended up sampling a site further south than originally planned, but it was still an area with a 10-mile long row of depressions and possible pockmarks. We were able to complete a 10-hour ROV dive, three box cores, and gather 820 bottom photos with the photo-platform.

What did we find? The exciting thing is that this is hands-down the most populated bottom area we sampled. There were thousands of sea cucumbers and anemones! Benthic jelly fish hovered above the bottom while fish and shrimp finned slowly by. There were large burrows, countless trails, and many burrowing urchins. The site was clearly a garden spot compared with the much less populated areas we had already explored. The puzzling thing was that we saw no evidence for gas or fluid seeps. No bacterial mats and no chemosynthetic animals of any kind. So the causes for the lush benthic life remain unclear.

The single pockmark we were able to explore is just one example of many that were detected by previous work and probably many more have yet to be mapped. And we only explored a small part of it. So, as is often the case in science, we narrow the focus of investigation, but by no means close off possibilities. There is no immediate support for the occurrence of gas seeps in this region—though it is still possible that they occur. Other possible explanations for formation of the pockmarks need to be considered more seriously, but are not proven either. The pockmarks could be scours from ancient ice sheets, for example. It is certain that they support an unusually high abundance of strange and beautiful life, and we should try to learn more about them through future exploration.

Sign up for the Ocean Explorer E-mail Update List.