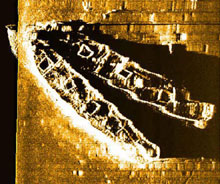

A sidescan sonar image of the complete Palmer (top) and Crary (bottom) wreck site provides a baseline map for ROV tracking. Image courtesy NOAA/NURC-UConn. Click image for larger view.

Ghost Gear on a Ghost Ship

Sept. 17, 2003

Anne Smrcina

Education and Outreach Coordinator

Stellwagen Bank National Marine Sanctuary, NOAA

Hurricane Isabel is working her way westward toward the coast, and we’ve been hearing reports of possible 3- to 6-ft swells tomorrow and even higher ones the rest of the week. If that forecast holds, it looks like this might be the last day of our mission, although we’re hoping to get a few good hours tomorrow morning. With large swells, the process of getting the vehicles into and out of the boat could be quite dangerous, while controlling the ROV (remotely operated vehicle) underwater could be problematic.

For today’s goal, the research and film crews decided to forego the Portland and visit the nearby site where the Frank A. Palmer and Louise B. Crary rest. Last year, a propitious sonar run (just after Portland imaging had concluded) produced one of the most fascinating sidescan images we had ever seen. There, sitting on the sea floor, were two ships, bow to bow, just as they sank minutes after they collided on a cold December night, according to survivors. These wooden schooners were carrying coal to an energy-hungry New England. Our goal was to determine which ship was which, and to compare the condition of the wrecks to that of the nearby Portland (approximately 2 mi away).

Although they were not significant in a historic sense, the two schooners were the bulk carriers of their day, serving the same role as today’s oil tankers. Of special note is that the Palmer was the largest four-masted schooner ever built, and the Crary was called one of the finest five-masters of her day (the Palmer was 274 ft long and the Crary 267 ft). Each carried a load of some 3,700 tons of coal on that fateful day -- December 17, 1902 -- both having filled their holds in Newport News earlier in the month.

As Hela continued on toward the bow, the research team saw that the end of the bowsprit is broken off, just as eyewitnesses to the accident reported a century ago. Image courtesy NOAA/NURC-UConn.

Hela, our ROV, entered the water around noon today and made the descent to the sea floor uneventfully. The new tracking system enabled us to navigate confidently toward the wreck, but the view that materialized through the silt-filled, murky water was one to put fear in the heart of any ROV pilot. As Hela focused in on the stern of the southernmost wreck we saw the rudder post, with the rudder hard to starboard. As Hela began to ascend along the hull, a massive ghost net appeared in the upper right quarter of the viewing screen.

Craig Bussel, the ROV pilot, quickly pulled the vehicle back and away. He brought her around the ship’s portside, where the currents helped sweep the ROV toward the bow just off the rail. There we saw a jungle of nets and lines, creating dense mats that at times obscured the decking and hull. Despite these impediments, Bruce Terrell, NOAA’s maritime archaeologist, definitely counted four sets of chainplate along the hull and believes an area now covered with nets is likely to hold the fifth set of plates. These plates are used to secure the rigging of each mast, so with five sets of plates, we’re confident that the southern vessel is the Crary.

In the second phase of today’s survey, the team brought Hela to the starboard side of the northern ship, which we believe to be the Palmer. In the debris field to the north, we started to follow a chain (possibly an anchor chain), but with nets everywhere, we had to abandon that plan. Other forays along that side of the ship revealed the broken-off head of the foremast. The high-definition camera gave us a beautifully clear look at the trestle tree (the area where the two sections of the mast are bound together) along with a pulley block from that area.

One of the Palmer's trestletrees with a block still intact lies on the sea floor. The trestletree attached the mainmast to the topmast of schooners. Image courtesy NOAA/NURC-UConn/The Science Channel.Click image for larger view.

After several further attempts to approach the vessel, we finally had to admit defeat. The garlands of fishing gear make a safe survey nearly impossible, and rather than lose the ROV, the team decided to call it quits. The day was not over, however, as we had another target to investigate nearby.

We dropped in right over a 50-ft fishing vessel, circa 1950s. Paint remained on the wooden hull, with a color scheme of red (probably copper anti-fouling paint) on the lower hull, a red rub rail at the water-air interface, and a white splashboard on the upper part of the hull. As we looked inward from the stern, we saw a hatch (perhaps to a stairwell), an open fish hold, and the pilothouse.

Craig maneuvered Hela to the open door and we peered in to see the steering wheel still in place. No name remains visible on the transom, as the wood in that area is quite heavily eroded, and many encrusting animals have taken hold. Again, as with the Portland and Palmer/Crary wrecks, a plethora of fishing gear was draped over the wreck. Although the stern wheels were full of cable, we could not tell if any of the fishing nets shrouding the boat actually came from the vessel itself.

Ben Cowie-Haskell, chief scientist for the mission, categorized the vessel type as an eastern-rigged side trawler. Although vessel identification was inconclusive, the research team theorized that the vessel was probably being towed when it went down, as the trawler had a rugged towrope tied around a forward bit. They also saw a big gaping hole in the starboard forward quarter, but could not tell how or when that damage was done.

What appears to be a towline is still attached to the forward bit. Image courtesy NOAA/NURC-UConn/The Science Channel.Click image for larger view.

Piecing together the stories of these wrecks involves more than just a visual survey with an underwater camera. Library searches for old newspaper clippings, digging into official vessel loss reports, finding original blueprints, and interviewing survivors or the families and associates of those lost at sea can all provide clues to resolve the mysteries of unknown shipwrecks. As the sanctuary continues to survey its maritime heritage resources, we will employ all of these methods.

Yet beyond the analytical portion of shipwreck investigations is the human- interest side that sparks our imaginations. Did this fishing boat, which rests a short distance from the Portland, snag the steamer with her gear, leading to her own demise? Did she collide with another vessel and sink before she could be towed to port? Did the Palmer and Crary actually get entangled and sink together? Some of these questions may never be answered. Some answers may only be revealed by dogged footwork.

In some cases, we can only theorize what happened based on the best available evidence. Nevertheless, heightened public interest in the discovery and investigation of these historic resources helps all of us to better understand the rich maritime heritage of the Stellwagen Bank National Marine Sanctuary and indeed, all of New England.

An Acadian redfish near one of the mystery wrecks. Image courtesy NOAA/NURC-UConn/The Science Channel. Click image for larger view.

Fishes of the Wrecks

Anne Smrcina

The differences between the Portland and the Palmer-Crary wreck sites extend beyond the archaeological and into the biological.

While all three vessels are heavily encrusted with benthic invertebrates, including anemones, sponges, and bryozoans, we’ve seen a distinct difference in the major fish communities at each site. At this point in time, the researchers cannot say whether the differences are due to the depth variations (the Portland is over 100 ft deeper than the Palmer-Crary) or whether there are other oceanographic or ecological factors at play. It may be mere chance that we saw particular fish on certain days, and other species may also populate the area. Both wrecks sit in muddy basin areas, are close to the lower edge of the photic (or light- penetrating) zone, and are subject to regular currents and cold temperatures.

Cusk swim near another shipwreck. Image courtesy NOAA/NURC-UConn/The Science Channel.Click image for larger view.

Generally speaking, Stellwagen Bank NMS and NURC-UConn scientists find redfish assemblages in deeper areas, such as muddy basins, while they are more likely to find gadids, such as cod and pollock, in shallower gravel fields. This seems contrary to what we see at the wrecks. In other ways, cod and pollock behaviors at the wreck sites and biological test stations have been similar, particularly with the pollock showing more active swimming in the water column and cod tending to lurk along the sea floor and among boulders and crevasses.

In our shipwreck surveys, both cod and pollock patrolled the Portland site. Cod were also found at the nearby fishing vessel and at the unknown wreck. As expected, the pollock were the more energetic group. Redfish guarded the Palmer-Crary wreck site in considerable numbers, with a vertical range that took them quite a distance from the muddy sea floor. Sanctuary researchers have observed that young redfish (less than 4 in long) use the spaces between piled boulders as protection from predators during daylight hours. At night they swim up into the water column to feed on invertebrate prey. As they grow larger, the redfish tend to move off the piled boulder reefs and into the surrounding areas, where cerianthid anemones provide cover.

Several pollock can be seen in this shot. Image courtesy NOAA/NURC-UConn/The Science Channel.Click image for larger view.

Some of the species observed during the shipwreck surveys were:

Atlantic cod: Seen at all sites, with large numbers at Portland. Atlantic cod is the State Fish of Massachusetts and a principal reason for the settlement and development of the New England colonies. It continues to be a major target of commercial fishermen in the region. The fish is golden-brown with white speckling, and has a prominent white ventral line that curves.

Pollock (Portland)

Acadian redfish (large numbers at Palmer-Crary

Winter flounder (common on muddy sea floor at all sites)

Longhorn sculpin (muddy sea floor)

Cusk (all sites)

Atlantic wolf fish (muddy sea floor near Palmer-Crary).