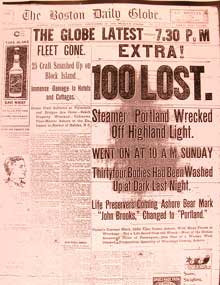

Because the passenger list was aboard the ship, the original loss of life was underestimated.

The Storm and the Ship

Provided by the Stellwagen Bank National Marine Sanctuary

The steamship Portland wasn’t the only victim of the monstrous gale that sank it in 1898. The "Portland Gale," named after the ship, wrecked more than 400 other vessels, killed more than 450 people, and left much of New England in shambles. The convergence of two high- energy, low-pressure systems, one from the Gulf of Mexico and the other from the Great Lakes region, conspired the night of Nov. 26 to spawn one of the most treacherous and deadly storms New England had ever seen.

On the morning of Nov. 25, a small low-pressure zone was forming over the western Great Lakes region and a larger low was gaining energy in the Gulf of Mexico. As the day passed, the Lakes system grew stronger and moved east, while the Gulf system gained energy and migrated northward toward the Gulf of Maine. The Lakes systems brought with it a cold front from Canada, while the other system brought humidity from the south. As these storms brooded on the morning of the 26th, Boston’s weather remained nice, driven by a high-pressure zone from Ohio that resulted in clear and cloudless skies. Although some snow had fallen in northern New England, business remained as usual in Boston.

That night, the sky began to darken and many boats stayed in port as a precaution. No one had any way to predict the severity of the impending calamity, and the Portland’s skipper, Hollis Blanchard, decided to stay on schedule. He captained his palatial ship into the night. As he steamed off toward Cape Ann, the wind began to howl and snow began to fall from Boston to the nation’s capital. At this point, the Lakes low had pushed Boston's high-pressure system northward to collide with the raging low from the Gulf of Mexico. Many smaller fishing vessels and ships raced into the shelter of Boston Harbor to escape the storm, passing the outward-bound Portland en route. Blanchard evidently thought he could outrun the tempest, but he couldn't. Turning the boat around was out of the question because steering it perpendicular to the wind would have capsized it. He had no option but to weather the storm at sea. Reports from lighthouse keepers and other boats at sea place the Portland anywhere from Cape Ann to Cape Cod throughout the evening.

As the evening progressed, Boston's Blue Hill Observatory took measurements until its gauges were either blown away or clogged with snow. Meteorologists estimated an average wind speed of 45 miles an hour through the night, with gusts of up to 90 mph. At one point during the night, 10 inches of snow fell in six hours.

In the morning, the people of New England awoke to a battered countryside. The storm had pounded the rail system into submission, downed telegraph wires across the region, and washed scores of boats ashore. The seas were so fierce that they had even altered the geography of parts of the Massachusetts coast. Grim news spread across the land sometime on the 27th, when bodies and life jackets from the Portland began to wash ashore, and within days, it became clear that everyone aboard had been lost at sea.

Portland's citizens were particularly hard hit by the tragedy because many of the people on board were from that community. In most cases, the families of the passengers and crew were unable to hold funerals for their loved ones because only a small percentage were found. Many families remained unsure whether their loved ones had even been on the steamer at all, since the only copy of its passenger list sank with the ship. Currently, historians estimate that 192 people went down with the steamer.

Built in 1889, the steamship Portland was a majestic white passenger vessel with gold trim and luscious velvet carpets. Her regular trips between Boston and Portland, Maine, took an entire night. At 281 feet long and 62 feet wide, the Portland drew only 11 feet of water, which made for easy steaming in shallow harbors. Unfortunately, as a side paddlewheel steamer, she was tall and narrow, which made her remarkably unstable in high seas. Although her construction enabled her to navigate Maine’s rivers, it was her downfall in the rough seas of the North Atlantic. After the disaster, propeller-driven ships began to replace paddlewheelers on the Boston-Portland route, and many captains made it a policy to send a passenger list ashore in the event of a disaster.