The Northern Gulf of Mexico Deep Water Habitats science party (less one participant, Peter Etnoyer). From left to right starting in the top row Catalina Martinez, Will Schroeder, Julie Olson, Sandra Brooke, John McDonough, Doug Weaver, GP Schmahl, Brett Phaneuf, Ron Hill, John Bratton, Sarah Bernhardt, Mary Wicksten, Suzanne Fredericq, Emma Hickerson, Taconya Piper, and Jenefer Savage. Click image for larger view.

Northern Gulf of Mexico

Deep Sea Habitats 2003

Mission Summary

September 21 - October 2, 2003

Catalina Martinez

NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration (OE)

![]()

![]() Video of the extraordinary biological diversity of the Gulf of Mexico. (QuickTime, 2.4 Mb)

Video of the extraordinary biological diversity of the Gulf of Mexico. (QuickTime, 2.4 Mb)

![]() Video of scientist using sampling techniques that have minimal impact on the Northern Gulf of Mexico Deep Water Habitats. (QuickTime, 1.9 Mb)

Video of scientist using sampling techniques that have minimal impact on the Northern Gulf of Mexico Deep Water Habitats. (QuickTime, 1.9 Mb)

The three discrete teams who collaborated on this exciting twelve-day cruise were led by scientists from NOAA’s Flower Garden Banks National Marine Sanctuary, the University of Alabama, and the Marine Conservation Biology Institute. Individual summaries from the three teams can be found below.

Despite time lost to mechanical difficulties and bad weather, twelve ROV dives were conducted successfully, involving more than 59 hours of bottom time, providing hundreds of digital still images and nearly 50 hours of digital video. Several hundred specimens associated with deep water coral communities were also collected for further study. This specimen bounty included various sponges, many algal species, more than 80 species of invertebrates, 21 coral species, and various fishes, as well as numerous geological samples. Scientists documented the presence of deep water coral communities at sites targeted for exploration, and the use of deep water corals as habitat for associated organisms was clearly documented during this expedition. More than 280 nm2 of ocean bottom were mapped with the Ronald H. Brown’s Seabeam echosounder, and several of these target sites were mapped at high resolution for the first time.

Education products and outreach efforts included updates on the Ocean Explorer Web site with daily logs and images during the expedition, the development or modification of eight lesson plans to fit with the goals and objectives of the cruise, and two Professional Development Institutes for Educators. At the conclusion of the expedition, a port event was held in Gulfport, MS, that included extensive media coverage and tours of the ship for about 150 students and teachers from local schools.

On behalf of OE, I would like to thank the crew of the NOAA Ship Ronald H. Brown, the crews of Sonsub and C&C Technologies, the scientific party, and the OE team for their dedication and hard work that resulted in another very successful cruise. It was an honor to participate in the exploration of yet another little-known region of our world’s oceans, and to be one of the fortunate few to witness the wonders of the deep water communities of the Gulf of Mexico first hand.

William Schroeder, University of Alabama

Sandra Brooke, Oregon Institute of Marine Biology

Julie Olson, University of Alabama

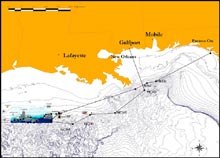

During the deep-water coral portion of the 2003 Gulf of Mexico Ocean Exploration cruise, we were able to use the Sonsub ROV to investigate 4 sites. These sites were located in lease blocks VK826, VK862, MC885, and GC354 (view expedition map).

The wide array of data collected throughout each dive provided us with the necessary information to meet the following proposal objectives:

- Documented the presence of deep-water branching ahermatypic corals (Lophelia pertusa and/or Madrepora occulata) at the four selected sites.

- Assessed the epibenthic community type at each site such that we can now begin to establish useful definitions for describing the stage of development for deep-water coral communities.

- Future in-depth analysis of the video footage will permit us to more fully characterize the morphological structure (colony size), developmental status (% live vs. dead), and spatial distribution patterns of coral colonies encountered at each site.

- Conductivity, temperature, and depth measurements recorded on each dive will be used to provide preliminary information regarding the hydrography (e.g., prevailing current, water temperature) while small samples of carbonate rocks and multibeam sonographs will provide a general characterization of the geology (e.g., substrate type, topography) present at each site.

- Collected video footage with precise locational information such that the offset in the available side scan sonographs can be identified and corrected.

- Collected fauna associated with the deep-water corals, including a squat lobster (Eumunida picta) that has not previously been documented in the Gulf of Mexico.

- Deployed an acoustic Doppler current meter at GC354 to characterize near-bottom current and temperature fields at the site over several months.

- Samples were obtained of live and standing dead coral that will allow us to begin to describe their reproductive habits, growth rates, and food resources.

- Additional samples were taken to characterize the microbial communities present in the water column, associated with the live and dead coral, and in the surrounding soft sediments in order to gain insight into the role of microorganisms as a food resource and as a mechanism for creating carbonate substrate.

Additional highlights of the cruise included filming vast fields of brilliant white anemones, starkly outlined against the dark brown of the surrounding mud; documenting massive gorgonians (6-7 feet high) with all of their associated organisms; and gaining a better appreciation of what life forms can exist 1500 feet below the ocean’s surface.

Lophelia pertusa, the bright white coral seen in the midst of a field of anemones and sponges, was one of the primary species of deep-water corals that we were interested in studying. It can occur as an individual colony, like this one, or in vast ‘thickets’ of many colonies clustered closely together. We are still in the process of learning what type of habitat is needed to support the growth of these corals. Click image for larger view.

We were privileged to work with an amazing group of scientists (many thanks to the Flower Garden Banks crew!), an incredibly supportive NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration staff, extremely helpful ROV and survey teams, and the highly professional crew of the NOAA vessel Ronald H. Brown. It was a very successful cruise but couldn’t have been done without everyone’s help!

Documenting Diversity of Deep Sea Corals in North American Waters

Peter Etnoyer

Marine Conservation Biology Institute

One of the goals of this summer’s expedition to the Gulf of Mexico’s deep sea habitats was to document the diversity of deep sea corals found in these waters. I collected, photographed, micro-photographed, and preserved more than 21 different species of Antipatharians, Gorgonians, Primnoids, and solitary corals. The amazing images of the polyps from these specimens will be a valuable resource to future expeditions seeking to document similar occurrences and distributions.

The Sonsub Innovator ROV cameras also video documented several octocoral species that were not collected, including a small field of the Bamboo coral Acanella and a large unknown red octocoral at 1700 feet. These collections will not be made until the population structure of those communities is better understood, and we can be more confident that those specimens are not the last of their kind. One of the very exciting finds of the trip was an organism with the branching morphology and axis of a gorgonian, but the dermis of a sponge. One might be inclined to suspect an encrusting sponge on a black coral’s axis, but we documented several of this particular specimen in more than one place. All results are forthcoming after a closer look at the Smithsonian Institute and the California Academy of Sciences. For now, some pictures will have to do.

The Northwest Gulf of Mexico Deep Sea Habitats Expedition was the first test of the Deep Sea Coral Collection Protocols, a brief document prepared by myself and the Deep Sea Coral Panel of Experts (DSC-POE) to improve our national capacity to document deep sea coral diversity. This document distills the advice of some our nation’s leading deep sea coral researchers including people from Harbor Branch Oceanographic Institution, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute, the Smithsonian, NOAA, Marine Conservation Biology Institute, Duke University, Oregon University, the University of Charleston, and the University of Connecticut. The intended audience for these protocols ranges from scientists to fishermen, and should provide everyone with everything they need to know to preserve a deep sea coral for the proper scientific authority, depending on the research question at hand.

These protocols proved very effective, challenging, very complete, and very time consuming! The preservation part is fairly straightforward, but the photo documentation takes a long time. Samples were preserved in triplicate to make them more available to outside researchers, and they were photo documented across their life cycle, “from the field to the Petri dish.” Regardless, by the time we venture forth next year, we will have what we call a positive ID for twenty new species, and some of the photo materials we need to assist our deep sea coral exploration teams in making these ID’s.

Another goal of this cruise was to document the way Deep Sea Corals provide habitat to associated species. We found excellent documentation of this at 1500 feet, where we found a large field of Callogorgia covered with skate egg cases. A single colony was home to as many as a dozen egg cases, and cases adorned more than half the organisms. We have found similar evidence of this particular habitat function for large shark egg cases in the Gulf of Alaska. This information is particularly important with regard to the 1998 reauthorization of the Magnuson Stevens Fishery Conservation Act, which requires the US Government to identify and protect essential fish habitat in all US waters. We found evidence for crab associations and elasmobranches, but as of yet, no apparent associations for fish. However, where we encountered deep sea corals, we inevitably encountered fishes. Do they like the lights or do they live there? Can one fish have more than one deep sea coral in a habitat? Do crabs and skates count as fish if we “fish” for them? Stay tuned, folks, we’re working on it!

The approximate route of the NOAA Ship Ronald H. Brown during the NW Gulf of Mexico cruise. Click image for larger view.

Reefs and Banks of the Northwestern Gulf of Mexico

G.P. Schmahl, Chief Scientist

Flower Garden Banks National Marine Sanctuary

The Gulf of Mexico rocks! Each time we have the opportunity to explore a portion of the deep reef communities of the northern Gulf of Mexico, we return with a new appreciation of this amazing marine ecosystem. This cruise, sponsored by NOAA’s Office of Ocean Exploration and carried out aboard the NOAA ship Ronald H. Brown, provided a window to directly observe deep reef communities and resulted in some very exciting discoveries. For this project, the research team of the Flower Garden Banks National Marine Sanctuary (FGBNMS) assembled an extraordinary group of specialists to continue the exploration and characterization of the reefs and banks of the northwestern Gulf. Our goal was to gather information to allow us to determine how this network of biological communities is interconnected, and how they contribute to the overall productivity of the Gulf. Sometimes I think that the northern Gulf of Mexico gets no respect. Many people think of this area as part of the well-publicized “dead zone” - a barren expanse of mud substrate, dotted with oil rigs and occasionally punctuated with a rocky outcrop. But nothing could be farther from the truth! In fact, the northern Gulf of Mexico has thriving coral reefs, rocky hard bottom teeming with life, chemosynthetic vent communities, deepwater coral assemblages, incredible fish resources, an endemic whale population, and much more. The diversity of life in the Gulf is nothing less than incredible.

A region of special significance lies along the edge of the continental shelf, where the gently sloping coastal seafloor begins to drop off rapidly into the depths of the Gulf. Here, located approximately 100 miles or more off the shore of Texas and Louisiana, lies a string of underwater reefs and banks of particular importance. These banks rise suddenly from the seafloor from depths of 500 feet or more, to within 100 feet or less of the ocean’s surface. This rapid rise in topography allows a dizzying variety of biological communities to develop. On this cruise, we were primarily interested in being able to classify those representative organisms which appear to be “signature” species that help define the biological communities. Often, although marine ecosystems are highly diverse, there is a subset of animals that are characteristic of distinct habitat types. In this way, scientists can classify marine communities by the occurrence of a few “key” organisms.

For this reason, the ability to collect representative species was critically important to the success of this mission. In this, the remotely operated vehicle (ROV) team from Sonsub more than lived up to the challenge. Throughout the mission, they worked tirelessly to build and refine systems for the ROV that allowed us to precisely collect organisms with as little damage to surrounding environments as possible. It was amazing to watch as one of the ROV pilots used the large mechanical manipulator arm to gently pick up a tiny crab, and place it in the collection bucket without a scratch! Working with such a dedicated group of professionals was a pleasure.

In summary, five remotely operated vehicle (ROV) surveys (24 hours of dive time) were conducted at three deep reef features: Alderdice Bank, West Flower Garden Bank, and Diaphus Bank (See figure 1). Close to 100 biological and geological samples were collected and processed. These collections resulted in two new (undescribed) species of algae, and multiple range extensions for fish and invertebrates previously unknown from this part of the Gulf of Mexico. In addition, approximately 1,000 square kilometers of bathymetric surveys were conducted of uncharted seafloor using the multibeam mapping technology of the NOAA ship Ronald H. Brown. These surveys revealed previously unknown deep reef systems south of the Flower Garden Banks Ecological Region. Finally, an open house event was held in Gulfport, Mississippi at the end of the cruise, during which over 150 middle school students toured the ship, and learned about the cruise events.

The summaries below have been provided from three key members of the science team that participated in this cruise.

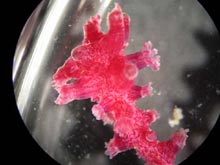

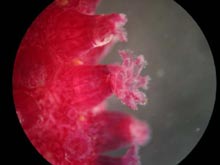

Collage of red algae collected at the West Flower Garden Bank, including two undescribed species (bottom right samples). Click image for larger view.

Red Algae of the Flower Garden Banks National Marine Sanctuary

Dr. Suzanne Fredericq

University of Louisiana at Lafayette

Even though seaweed sampling was restricted to two ROV dives at the West Mound of the West Flower Garden Bank, the limited collections reinforced previous FGBMNS sightings conducted in the region with a smaller ROV that the deep-water marine flora at 150-250 ft is surprisingly diversity-rich and has predominantly tropical affinities. A new gelatinous species was collected that belongs in the species-poor red algal family Nemastomataceae as well as a large unknown species of Halymenia (Halymeniaceae); these two specimens were reproductive which will aid in their characterization and correct taxonomic identity. Excluding the crustose corallines, a total of twenty-two species of leafy seaweeds were collected during the first dive, and sixteen species were retrieved during the second dive. New range extensions into the Gulf of Mexico were noted for several species. It was striking that the abundance of coralline red algal nodules or rhodoliths at these deep depths was crucial for the support and survival of the seaweed assemblages, as in areas lacking rhodoliths at similar depth ranges, the bottom of the ocean floor was completely devoid of macroalgae.

A collage of several of the more conspicuous invertebrates sampled during the cruise – some of these are still awaiting identification. Click image for larger view.

Invertebrates of the Deep Reefs

Mary K. Wicksten

Texas A&M University

Other than soft corals and black corals, our group collected and photographed specimens of at least 80 species of invertebrates. Many of these are large corals or starfishes that have been photographed before, but are unidentifiable without a specimen. These specimens will be identified at Texas A&M University or sent to specialists for identification. We collected some tiny shrimp, crabs and brittle stars among rocks and sponges. These tiny animals include several that represent the first records of their species on the banks. We have new host records of tiny shrimp that live in association with sponges or sea urchins. Knowing the exact location at which these specimens were taken, we can better define communities of algae, invertebrates and fishes.

The new records will contribute to a large scientific report that will compare the species richness between the northern banks of the Gulf of Mexico. We can compare our new records with those reported by biologists since 1972. Information on living color, habitat and distribution will be included in scientific works on hermit crabs, shrimp, starfishes and sea anemones of the Gulf of Mexico.

Another goal of this cruise was to document the way deep-sea corals provide habitat to associated species. We found excellent documentation of this at 1,500 feet, where we found a large field of Callogorgia covered with skate egg cases. A single colony was home to as many as a dozen egg cases, and cases adorned more than half the organisms. We have found similar evidence of this particular habitat function for large shark egg cases in the Gulf of Alaska. This information is particularly important with regard to the 1998 reauthorization of the Magnuson Stevens Fishery Conservation Act, which requires the US Government to identify and protect essential fish habitat in all US waters. We found evidence for crab associations and elasmobranches, but as of yet, no apparent associations for fish. However, where we encountered deep sea corals, we inevitably encountered fishes. Do they like the lights or do they live there? Can one fish have more than one deep sea coral in a habitat? Do crabs and skates count as fish if we “fish” for them? Stay tuned, folks, we’re working on it!

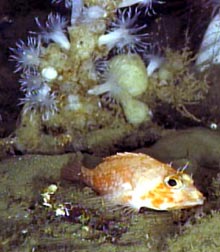

Basalt blocks at the base of one of the spires of Alderdice Bank with a trumpetfish in the foreground. Click image for larger view.

Geology Highlights

John Bratton

US Geologic Survey

The ROV footage and samples collected on the cruise documented the range of hard substrates important to deep-sea organisms in the study area, especially corals.

Six classes of hard elements were observed:

- Erosional bedrock outcrop

- Transported bedrock fragments (cobbles and boulders on slopes)

- Authigenic carbonates associated with seeps

- Small biogenic carbonates (shells, coral fragments)

- Large biogenic carbonates (including drowned and encrusted branching corals and relict algal nodule fields)

- Salt tectonic exposures (basalt, anhydrite, bedrock exposed on fault scarps).

The following two important generalizations can be made about hard substrates in the deep Gulf:

- Relic (remnant) biogenic structures formed during times of lower sea level (e.g., drowned reefs and algal nodule fields) provide significant attachment surfaces for modern deep benthic communities at depths of approximately 50 to 150 m (West Flower Garden Bank, Diaphus Bank).

- Deeper benthic communities (>150 m), especially associated with steep slopes or canyons, are more dependent on bedrock outcrops, authigenic carbonates, and small biogenic carbonates (shells, coral fragments) for attachment sites.

The most common bottom type, soft mud, supports less diverse communities of infauna (polychaetes, bivalves, isopods), epifauna (cerianthid anemones), and eel-like fish (conger eels, morays, rattails, grenadiers, hagfish).