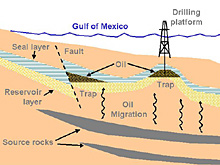

The ROV pilot used a "clamshell" collecting apparatus to capture this elusive tinsel fish. Click image for larger view.

Green Canyon Encounters:

A Silver Fish, a Yellow Star, Two Pink Posers, and Three Orange Lobsters

September 25, 2003

Catalina Martinez

NOAA OE

Sarah Bernhardt

Flower Garden Banks National Marine Sanctuary

NOAA

The multibeam team worked into the wee hours of the morning to acquire data at Green Canyon 354, so that two-dimensional images could be generated to aid in the selection of suitable dive targets scheduled to begin once the mapping was complete. The deep coral research team started their final ROV survey at 7 am. This ROV (remotely operated vehicle) dive was supposed to end at noon, but due to the sighting of an unusual tinsel fish, the ROV remained on site attempting to capture the elusive creature.

A crowd gathered in the main lab around the video monitors, and cheers and laughter could be heard throughout the scientific deck level as the ROV pilot strategized with the scientists about how to attempt to capture their prize. They tried sucking the fish up with a specially designed suction device on the ROV. The fish swam away. They tried cornering the critter with the manipulator claw -- to no avail. They even tried to sneak up on it with the "clamshell" grabbing apparatus, but this amusing fish just picked up a little speed every time the jaw of the clamshell started to close, and managed to swim out of reach.

Clearly, this fish was too clever for the ROV! In the end, the ROV pilot was unable to capture this individual for positive identification, although it may have been the first record of this species ever documented in the Gulf of Mexico. We collected a great deal of video footage, though, so the creature eventually may be positively identified.

Several small, bright orange squat lobsters were collected among the deep- sea corals and sea fans at Green Canyon. These interesting creatures could swim backwards, and each had distinctive white racing stripes along the length of its carapace. Mary Wicksten, the invertebrate zoologist on board, identified these colorful specimens as the three-toothed squat lobster, Munidopsis tridentata. Prior to this documentation, this colorful creature was known from only three specimens, and only one of the three had been collected in the Gulf of Mexico. This original Gulf of Mexico identification had been made from an incomplete specimen, and the distinctive markings were never before recorded, possibly because color is typically lost once an organism is placed in the chemicals that preserve them. Thus, our documentation of three males of this rarely collected species is quite exciting.

Sediment and coral samples were also collected on this dive, as was a lovely gorgonian and an unidentified yellow sea star that somehow never made it to the end of the ROV vacuum tube.

As the Sonsub technicians took the collection buckets off the ROV, the samples were handed to scientists who then cataloged and processed them for later analysis in their labs.

A great many weird and wonderful creatures were encountered here at Green Canyon. Stand by as we transit to Alderdice Bank on the edge of the continental shelf (view expedition map).

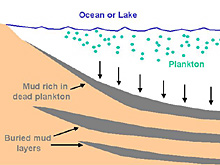

Oil is a fossil fuel formed from plankton that is deposited in the sediments of oceans and lakes, and then buried deeply in the earth. Click image for larger view.

The ABCs of Oil

September 25, 2003

John Bratton

U.S. Geological Survey

Woods Hole, MA

The Gulf of Mexico is one of two areas in the United States where offshore production of oil takes place -- the other is California. Whether onshore or offshore, however, every oil deposit requires four things.

- Source rock

This is the rock from which the oil is originally formed. Source rocks are usually fine-grained shales formed from ocean or lake mud that contained lots of plankton, especially single-celled algae called diatoms. Higher concentrations of plankton in the sediments increase the likelihood that the rock will one day yield oil.

- Reservoir

Once droplets of oil start to form in the source rock, they float upward through tiny pore spaces because they are lighter than the ground water that is also present in the rock. They cannot yet flow freely or be pumped out of the ground. They first need to collect in some sort of porous layer, such as a sandstone or a fossil limestone reef, that contains open cracks and cavities. Such a formation is called a reservoir.

- Trap

Triangular trap structures formed by faulting, or domed structures formed by folding of rock layers, allow oil to collect in one place and eventually to be recovered from a reservoir by drilling.

- Seal

After oil starts to collect in a trap, it needs something to keep it there; otherwise, it would just flow out of the cracks and pores to the sea floor or ground surface. A barrier must exist to prevent this. Typical barriers are shales that are either (1) deposited above the reservoir layer, or (2) brought into contact with it by movement along faults.

If these four requirements are all present, the only other necessary ingredients are time, pressure, and heat. If the temperature is high enough, some of the oil will be converted into natural gas, which collects in the same way and sometimes in the same traps as oil.

Recent advances in offshore drilling have increased the efficiency of locating and recovering petroleum (a collective term that includes both oil and gas), and have decreased the environmental impacts of this process. Some of the most significant technological breakthroughs follow.

- Three-dimensional imaging of rock layers under the sea floor is now possible because of new at-sea tools and advances in supercomputer processing power.

- Designs of new drilling platforms, such as tension-leg platforms and spars, make it affordable to drill in very deep water, too deep for building conventional platforms that stand on rigid towers.

- Directional drilling permits wells to be advanced in any direction from a single hub platform, including significant horizontal offsets from the starting point following oil-bearing layers.

- Underwater completions allow wells to be drilled from mobile platforms such as ships, and then transformed into oil-producing mode with structures built on the sea floor by underwater robots. These sub-sea completions are then connected to platforms and shore by underwater pipelines.

So next time you ride in a car, cook dinner, or use your computer, keep in mind that the energy you are using might have come from plankton buried long ago, and pumped in the form of oil from deep beneath the ocean.