by Scott C. France, University of Louisiana at Lafayette

Ellen Kenchington, Fisheries and Oceans, Canada at the Bedford Institute of Oceanography

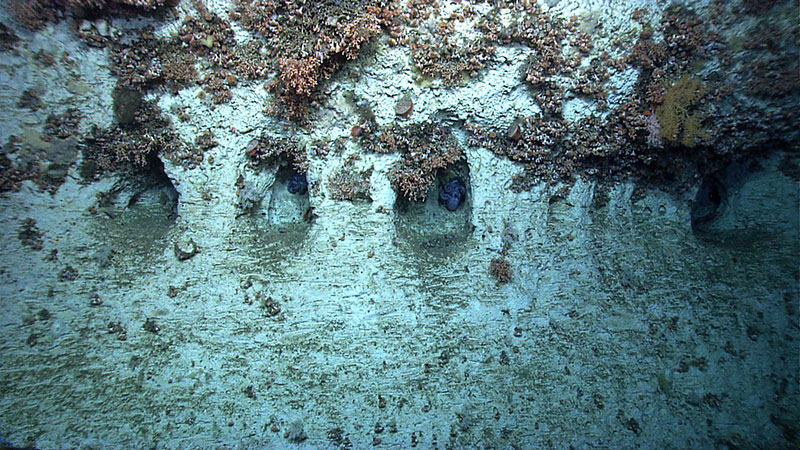

A cluster of deepwater corals grows on hard substrate exposed on the western wall of Oceanographer Canyon. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, Northeast U.S. Canyons Expedition 2013. Download image (jpg, 1.4 MB).

When one considers familiar land-based (terrestrial) organisms and the habitats they live in, it is easy to envision the gaps that separate them. For example, mammals of the forests live in patches (of various sizes) surrounded by meadows or grasslands or urbanized areas. You may have heard about the importance to conservation of wildlife corridors, which are narrow zones of habitat that connect larger habitat patches. These corridors allow animals reliant on these habitats to safely move from patch to patch, which in effect creates an overall larger living space for them.

The oceans can appear to be a homogeneous body of water through which animals can move freely; however, that view is deceptive and we know that marine animals and plants are found in specific habitats and areas and that their distributions can range from whole ocean basins to specialized locales. Species distributions are governed by their physiological requirements (such as food availability, temperature, salinity, pressure tolerance, light) and also by limitations on their ability to move freely through the water. This last point is especially critical for species that live attached to the seafloor, sometimes miles below the surface, like corals and sponges. Such species primarily spread through the movement of their small reproductive bodies and larvae.

Understanding what the factors are that control the distribution of a species is important for predicting the impacts of human activities on them and for developing solid plans for their protection where needed.

Steep slopes and water flow create sediment-free habitats for deepwater animals. Here in "East of Veatch" Canyon, small cave-like features have been eroded in a wall in which octopus brood their eggs while corals grow from the overhang above them. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, Exploring Atlantic Canyons and Seamounts 2014. Download image (jpg, 1.8 MB).

There can be many barriers to movement in the ocean such as currents, tides, and temperature or salinity changes in the water column. In the deep sea, there can be different layers of water lying over top of one another and sometimes moving in different directions and originating from different places, such as the Antarctic and the Arctic.

For attached species living on the seafloor, the type of bottom (hard or soft) is an important factor for most. Such habitats may be patchy in their distribution and in turn limit the places where a species may occur. A core question for studies of connectivity is whether deep-sea animals can travel readily among separated patches of habitat.

When scientists study connectivity, they are asking about how – and to what degree – isolated or widely dispersed populations are connected to one another. Connectivity can be examined in a couple of ways: are there corridors linking isolated habitats and is there interbreeding among populations living in those habitats? This second perspective examines “gene flow,” the maintenance of genetic relatedness of populations through the exchange of genetic material, such as through sexual reproduction.

There is an important distinction between these two concepts: even though populations may be connected through habitat, that does not mean they are necessarily moving throughout that habitat. If they are not, the populations may become genetically isolated. To determine the degree of genetic connectivity, scientists require tissue samples that can be analyzed in the lab for DNA sequences.

One patchy habitat that we will explore on this expedition is submarine canyons (think of the Grand Canyon underwater!). Submarine canyons are scattered along the coasts of North America and elsewhere and can provide patches of hard substrate formed by the canyon walls that expose hard surfaces (that is, they are not buried under sediment) on which animals can attach.

The shape of some canyons funnels sediments and organic material (food for deep-sea animals!) from the shallower continental shelf to the deeper abyssal seafloor, and their impact on hydrodynamics (or water flow) may alter the physical conditions (e.g., temperature, oxygen, current speed) relative to the surrounding continental slope.

Do the deep-sea animals specialized to live in the different canyons spread between Canada and the United States (one boundary that the animals do not recognize!) move readily among these separated patches of habitat?

The deep sea of the North Atlantic is connected across international boundaries – the habitats and the animals living in them are not bounded by borders, and so to study connectivity, we need a multi-national approach, research cooperation across nations. This is the intent of the Atlantic Seafloor Partnership for Integrated Research and Exploration, or ASPIRE, initiative.

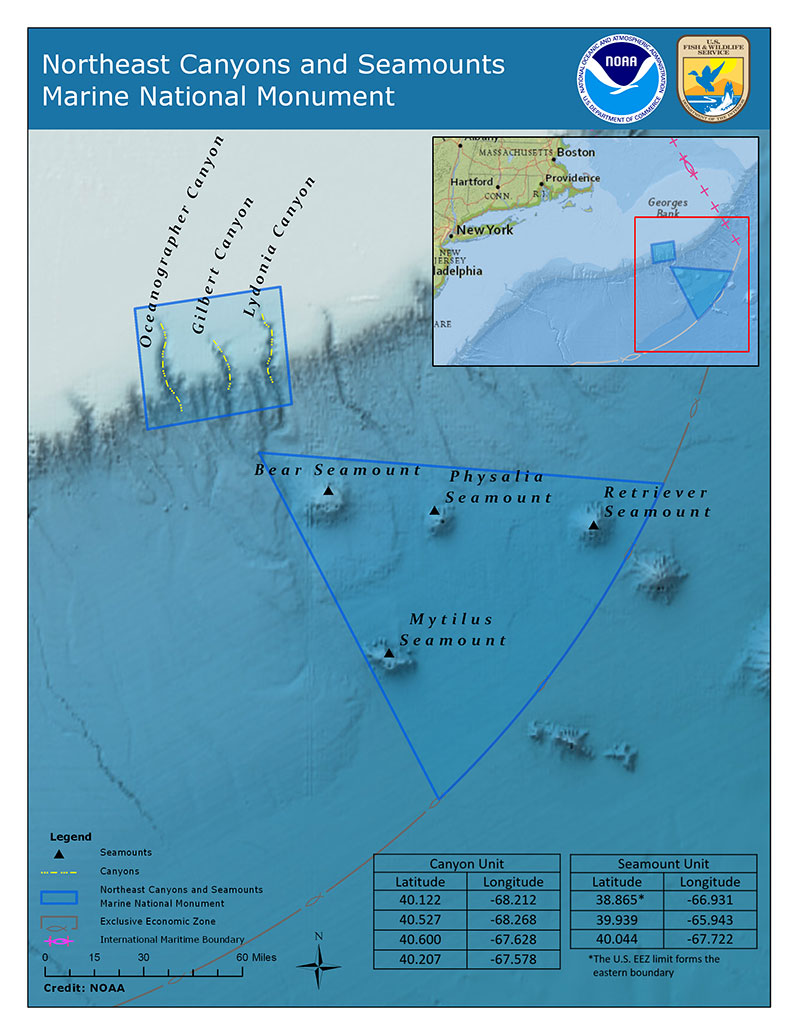

This map of the Northeast Canyons and Seamounts Marine National Monument shows some of the submarine canyons that cut into the deep seafloor of the continental margin of the eastern United States and the seamounts offshore. The habitat characteristic of these geological features is discontinuous, with communities isolated by the sediment-covered slopes between them. Image courtesy of NOAA. Download image (jpg, 2.0 MB).