By Bill Chadwick - Oregon State University and NOAA Pacific Marine Environmental Lab

May 2, 2016

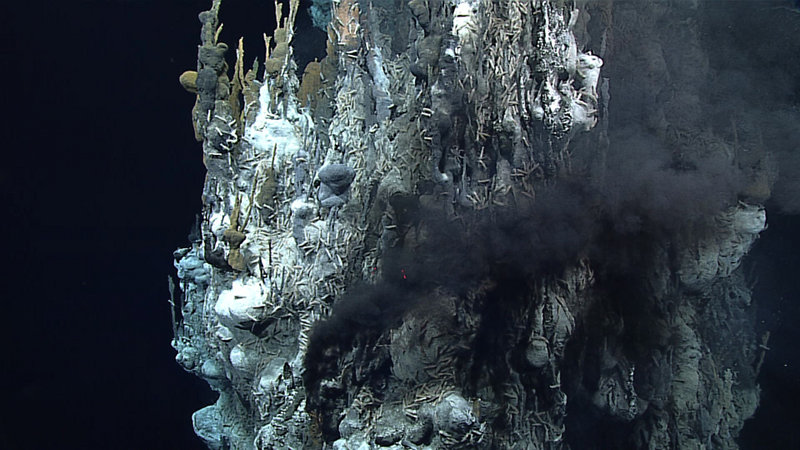

Actively venting hydrothermal vent chimney shrouded in black smoke and covered with vent animals including shrimp, crabs, snails, and scaleworms. Image courtesy of NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, 2016 Deepwater Exploration of the Marianas. Download larger version (jpg, 1.1 MB).

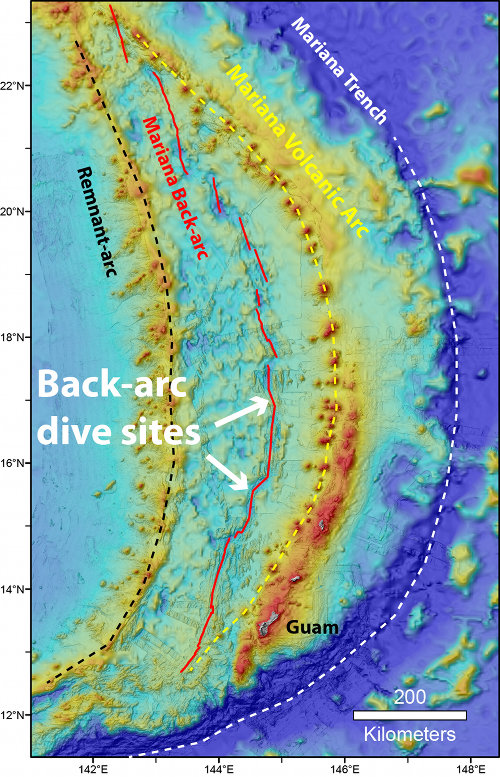

Dives 9, 10, and 11 on this expedition were all made on the Mariana back-arc, a deep rift valley where seafloor spreading is occurring and volcanic eruptions provide the heat to create hydrothermal vents and their unique biological communities.

Dive 10 involved searching for a new hydrothermal vent site on the back-arc axis at latitude 15.5°N, where the Falkor cruise found clear evidence for hydrothermal plumes above the seafloor. The dive started at 3,863 meters and traversed mounds of pillow lavas that were probably hundreds of years old, based on the amount of sediment that had accumulated on them.

Map showing locations of ROV dives in the Mariana back-arc. Image courtesy of NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, 2016 Deepwater Exploration of the Marianas. Download larger version (jpg, 1.2 MB).

These three dives build upon recent discoveries that were made during an expedition last December on R/V Falkor and supported by the Schmidt Ocean Institute and the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research. On that cruise , a science team from Oregon State University, University of Washington, and NOAA Pacific Marine Environmental Lab searched for new hydrothermal vent sites along 600 kilometers of previously unexplored Mariana back-arc.

That expedition found four new hydrothermal vent sites, and by chance, also discovered a recent eruption site with lava flows that were emplaced between 2013 and 2015. The Deepwater Exploration of the Marianas expedition provided an opportunity to conduct the first detailed remotely operated vehicle (ROV) explorations of these sites using NOAA Ship Okeanos Explorer and the Deep Discoverer remotely operated vehicle (ROV).

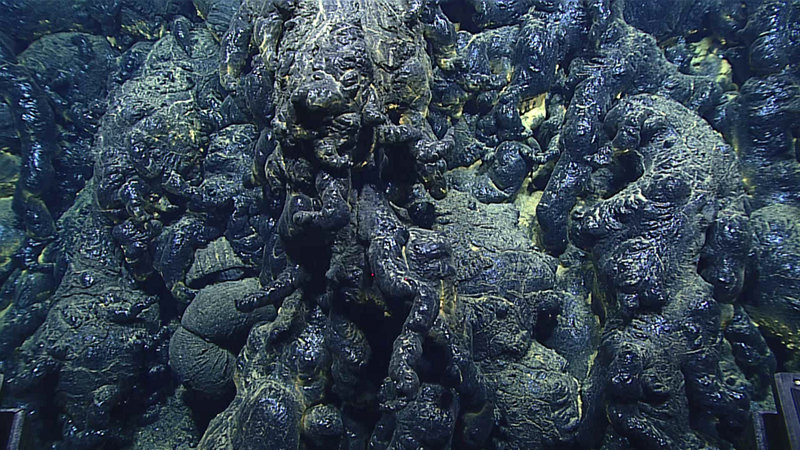

Shiny black pillow lava with many finger-like “buds,” from the recent eruption site that is less than three years old. Image courtesy of NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, 2016 Deepwater Exploration of the Marianas. Download larger version (jpg, 1.8 MB).

On Dive 9, the science team explored the brand new lava flows on the back-arc axis near latitude 15.4°N. The ROV descended to a depth of 4,066 meters and landed right on the new lava, which is dark and shiny because it is covered with volcanic glass which forms when the lava cools very quickly in contact with cold seawater.

When lava flows underwater, it creates a variety of forms that are not found on land, because of this rapid cooling effect. The most common of these forms is called “pillow lava,” and we saw a lot of this on the dive, some of which had an extraordinary number of thin glassy “fingers” or “buds” extending outward in all directions from the main pillow lobes. There was a lively debate among the scientists participating in the dive about how and why these delicate fingers formed, because they are very unusual.

As Deep Discoverer explored the new flows, we also found patches that were covered with hydrothermal sediment, clear evidence that hot water had been venting out of these areas as the lava cooled. These lava flows are an exciting discovery because eruptions along the Mariana back-arc probably only occur once every few hundred years or so, and this dive was a rare opportunity to explore some of the newest seafloor on the planet.

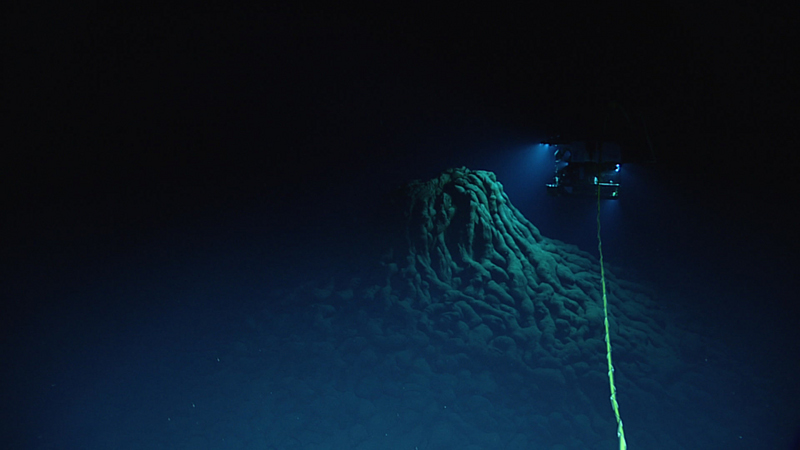

ROV Deep Discoverer explores an eruptive vent at the top of a large mound of pillow lavas. Image courtesy of NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, 2016 Deepwater Exploration of the Marianas. Download larger version (jpg, 443 KB).

Remarkably, at the top of each mound there was a cone-shaped feature a few meters high made of long pillow lava tubes that radiated out in all directions. These “haystacks” were the eruptive vents where lava last flowed to form these mounds. The mounds themselves are each tens of meters high and hundreds of meters in diameter.

Despite a wide-ranging search with the ROV, we were not able to find the hydrothermal vents we were looking for during our limited time on the seafloor. The experience reminded us about the remoteness and isolation of deep-sea hydrothermal vents and how they are oases of life in the vast darkness of the ocean abyss. Searching for them can seem like searching for a needle in a haystack.

But we haven’t given up on this hydrothermal hunt. We know these vents are nearby somewhere, and this location in the back-arc is an important link between other known vent sites far to the north and south, so we will continue the search during our next opportunity when the R/V Falkor returns in December of 2016.

Dive 11 was another dive to search for a new hydrothermal vent site that was discovered during the Falkor expedition, this time on a different segment of the back-arc at latitude 17°N. Here, we had more precise information about where to look for the vents - and that made all the difference.

Soon after the ROV touched down at 3,292 meters, we drove toward a large mound of sulfide blocks that was the base of a 30-meter-high active venting chimney. It was an extraordinary sight!

The chimney had innumerable narrow spigots that were belching hot fluids with black mineral-laden smoke. We measured a temperature of over 339°C in one of them. Around these hot vents, the sides of the chimney were bathed in warm shimmering water and covered with vent-endemic animals that are specifically adapted for life at seafloor hot-springs. And that was just the beginning!

As we traversed from west to east, we encountered several more groups of chimneys, each actively venting and each supporting its own thriving community of life. One of the more intriguing places we visited during the dive was a large cone that is about 50 meters wide, 10 meters high, and with a crater in the center. It looks like a volcanic cone – but it appears to be made of hydrothermal sulfide deposits, had patches of diffuse flow along the rim, and was covered with animals. This really had us scratching our heads – we’d never seen anything like it. But that is half the fun of exploration – seeing things you’ve never seen before and didn’t even expect to find and trying to figure them out.

This was an awesome end to our three-dive sequence in the back-arc. We all felt lucky to have a chance to be the first to explore this extraordinary place.