By Bill Chadwick - Oregon State University and NOAA Pacific Marine Environmental Lab

June 26, 2016

Dives 5, 8, and 9 of the third leg of the 2016 Deepwater Exploration of the Marianas expedition were made at three active submarine volcanoes - Ahyi Seamount, Eifuku Seamount, and Daikoku Seamount.

These three seamounts are part of the Mariana Volcanic Arc, which is a chain of over 60 active volcanoes stretching over 600 miles west of and parallel to the Mariana Trench. Two of the three sites are part of the Marianas Trench Marine National Monument. All three were found to be hydrothermally active, but each has a different story to tell.

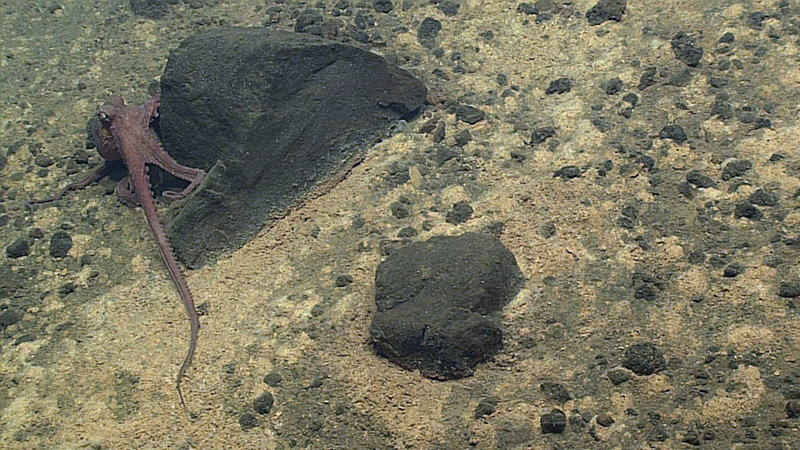

A curious octopus greets the remotely operated vehicle at the beginning of Dive 5 at Ahyi Seamount. Image courtesy of NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, 2016 Deepwater Exploration of the Marianas. Download larger version (jpg, 1.8 MB).

We know that Ahyi Seamount erupted in April-May of 2014, and Dive 5 was the first opportunity to explore what happened during that event.

A series of underwater explosions were recorded over about three weeks at Ahyi by the seismic network in the northern Marianas operated by the U.S. Geological Survey. During that time, a team of scuba divers from NOAA who were surveying the coral reefs at the neighboring island of Farallon de Pajaros, located only about 12 miles away, heard and felt the underwater explosions while they were surveying the coral reefs.

Subsequent sonar re-surveys of Ahyi seamount during an expedition in December 2014 supported by the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research found that a new crater had formed near the summit of the seamount and that a landslide had descended the south flank.

Dive 5 during this cruise started southwest of the summit of Ahyi, at a depth of about 350 meters, where we were greeted by a curious octopus. Our main aim was to explore the areas downslope of the new crater, and as we traversed that area, we found a slope covered with ashy sediment and white microbial mats, an indicator of hydrothermal activity.

The remainder of the dive explored the rocky outcrops southeast of the summit, where we discovered amazing nearly vertical cliffs of older lava with spectacular columnar joints (parallel cracks formed by slow cooling and contraction). Because the environment near the top of an active volcano is obviously unstable, most of the animals we observed were mobile. Farther from the vent there were more sessile animals that had apparently survived the eruption.

Long-spined sea urchins were some of the animals found during the dive at Eifuku Seamount. Video courtesy of NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, 2016 Deepwater Exploration of the Marianas. Download (mp4, 74.7 MB).

Dive 8 was the first-ever remotely operated vehicle (ROV) dive made at Eifuku Seamount. A hydrothermal plume had been discovered over this submarine volcano in December 2014, and this was the first opportunity to search for hydrothermal venting on the seafloor.

The dive started by traversing across a large volcanic crater to the south of the summit. Inside the crater we found a dome of viscous lava that appeared to be only a few decades old, based on the few numbers of sessile animals that had colonized the rocks.

On the far side of the crater, the ROV continued to traverse up the steep wall of the crater, and there we found the hydrothermal vents. A large area was covered with orange and yellow hydrothermal deposits, and we saw warm, shimmering water coming out of the seafloor in many areas. Curiously, however, we saw no vent-specific animals living near the seafloor hot springs.

As the ROV continued up the crater wall, we returned to normal (non-vent) seafloor habitat and animals, showing that the area of active venting only extended over a limited depth range. Outside the hydrothermal area, we encountered an amazing variety of octocorals, anemones, urchins, seastars, nudibranchs, and colorful fish.

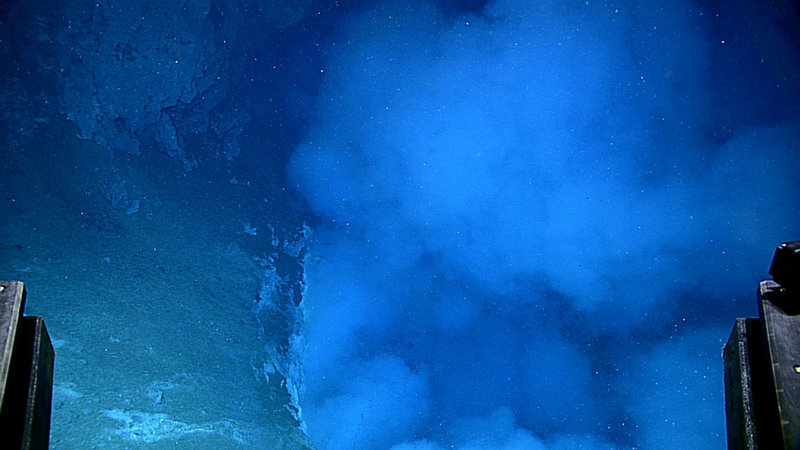

During Dive 9, we explored the crater of Daikoku Seamount, observing active venting and thick volcanic smoke, supporting the hypothesis that there had been recent volcanic activity in the area. Plumes of likely carbon dioxide gas and sulfur were emanating from cracks and orifices near the crater rim and along the lower wall of the crater. We saw tubeworms, crabs, and a high density of flat fish specialized in living on the sulfur rich ground. Video courtesy of NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, 2016 Deepwater Exploration of the Marianas. Download (mp4, 72.3 MB).

Daikoku Seamount was found to be erupting during a previous expedition in December 2014, evident from high levels of hydrogen in the water column above the volcano. This was the first opportunity to see what had happened on the seafloor during the eruption. Daikoku was previously known to have a remarkable hydrothermal system characterized by high-sulfur output and a unique ecosystem characterized by a new species of vent-endemic flatfish.

We wondered whether the recent eruption had disrupted that ecosystem. Were the sulfur pond and the flatfish still there?

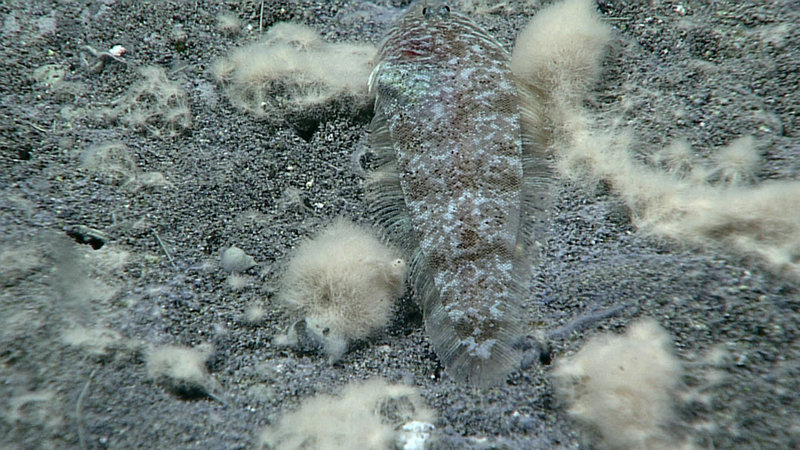

One of the well-camouflaged flatfish that live in the high-sulfur environment on Daikoku seamount in extraordinary numbers. Image courtesy of NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, 2016 Deepwater Exploration of the Marianas. Download larger version (jpg, 1.1 MB).

Dive 9 began on a slope covered with white sulfur crusts and we immediately encountered an extraordinary number of the flatfish on the bottom. In fact, the flatfish seemed to be even more dense and numerous than we had seen previously.

Clearly, they are perfectly adapted to this harsh volcanic environment that would be toxic to other species. We don’t fully understand how the flatfish thrive so well here, and we had lively discussions of whether or not they might have microbial symbionts that help them survive.

The molten sulfur pond appeared to still be active, but a dense sulfur plume prevented us from confirming this definitely.

Later in the dive, we explored an area where two summit craters had combined into one larger crater as a result of the eruption. The crater rim was surrounded by rocky outcrops where vent-endemic tubeworms, anemones, and barnacles were covered with ash from the eruption. It’s remarkable that these species (along with the amazing flatfish) are still thriving in this dynamic and ever changing environment, that both sustains them and continually challenges them, living at the top of an active volcano!

This dense sulfur plume was probably coming from a pool of molten sulfur on the seafloor. Image courtesy of NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, 2016 Deepwater Exploration of the Marianas. Download larger version (jpg, 823 KB).

Tubeworms and anemones are covered with ash from the 2014 eruption, but appear to be still thriving at Daikoku Seamount. Image courtesy of NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, 2016 Deepwater Exploration of the Marianas. Download larger version (jpg, 883 KB).