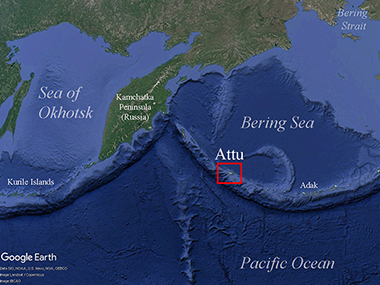

Exploring Attu’s Underwater Battlefield and Offshore Environment

Dates

July 17 - 27, 2024

Vessel

Research Vessel Norseman II

Location

Aleutian Islands

Primary goal

To bring attention to the World War II Battle of Attu (1943) through surveying and inventorying Attu’s maritime heritage sites. Additional goals include answering questions about Attu’s pre-war maritime history, contributing to our understanding of Attu’s marine environment and the history of Unangax̂ displaced by the U.S. government during the war, and providing a foundation for further work to locate U.S. and Japanese service personnel missing in action.

Primary technologies

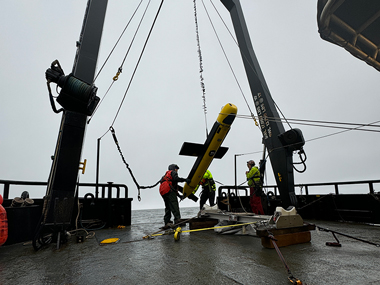

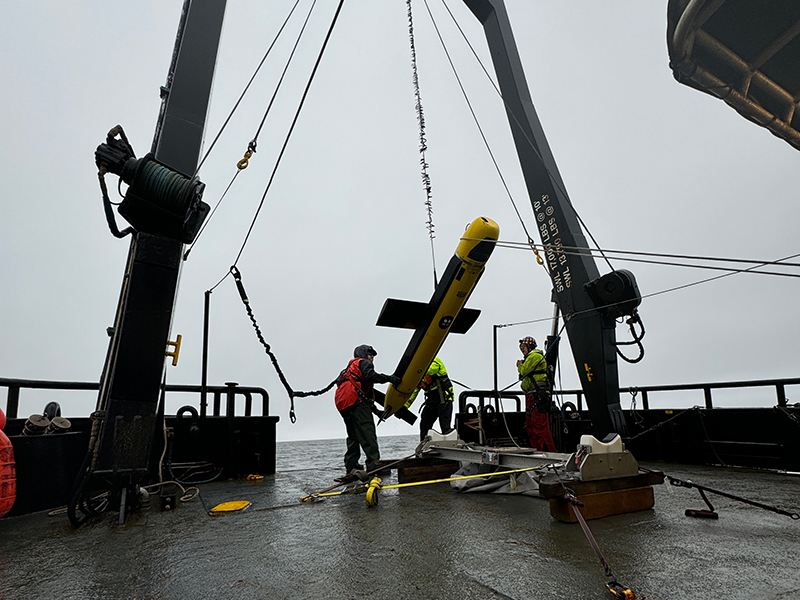

AquaPix Miniature Interferometric Synthetic Aperture Sonar (MINSAS; Kraken Robotics), SeaScout-2 towfish (ThayerMahan), BlueRov2 remotely operated vehicle (ROV; Blue Robotics, Inc.), underwater photogrammetry system MURAKUMO

Expedition Summary

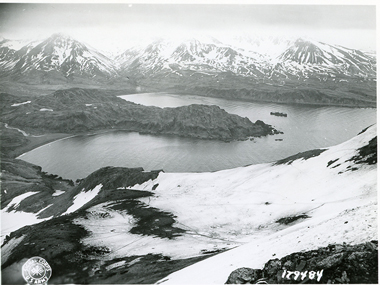

On July 17, 2024, the expedition team, consisting of archaeologists, hydrographers, and engineers, boarded the research vessel Norseman II at the Aleutian island of Adak. From there, the converted crabbing ship made the 49-hour steam to Attu, arriving in the early morning hours. Aided by years of archival research that preceded the expedition, the team wasted no time in getting started. A total of 12 synthetic aperture sonar (SAS) and multibeam surveys were conducted, including two aimed at imaging a specific wreck following its initial discovery. In all, the research team performed nearly 36.4 hours of sonar operations, corresponding to 435 linear kilometers and 35.3 km2 surveyed. The team focused on 11 locations around Attu, with water depths ranging from 15 meters (~40 feet) to 90 meters (~300 feet). The acoustic imaging was complimented by 21 deployments of the camera-equipped remotely operated vehicle (ROV), sent to photograph sonar targets of interest. Following the final SAS survey on July 24, with five days of extensive survey operations completed and terabytes of data, the expedition team bid Attu farewell, successfully completing the first underwater archaeology project in the island’s history.

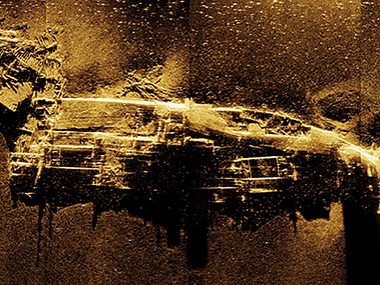

The initial survey work focused on the suspected location of the SS Dellwood, a U.S. Army cable layer that sank in July 1943. Hydrographers from ThayerMahan, Inc. deployed their SeaScout Katfish system, equipped with both cutting-edge synthetic aperture sonar (SAS) and more traditional multibeam sonar. Eighty-one years to the day of its sinking, the SS Dellwood was found in about 34 meters (110-115 feet) of water, though its physical state appeared far more disarticulated than expected. While the site is in an area of strong currents and ripping tides, the complete dismantling of the 3,000-ton vessel suggests that it may have been intentionally destroyed in hopes of making it less of a navigational hazard. A research consortium from Japan led by A.P.P.A.R.A.T.U.S., Inc. deployed their ROV and captured video footage of the severely damaged wreck site, while Norseman II’s captain held the research vessel in place. The optical imagery not only helped to validate the identification of the wreck as the remains of Dellwood, but will also be used to characterize the wreck’s ecology and serve as a valuable education product.

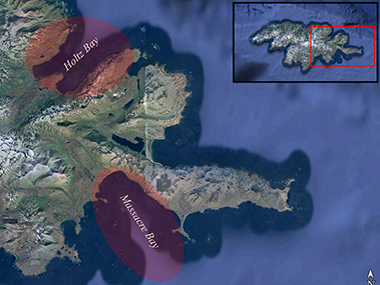

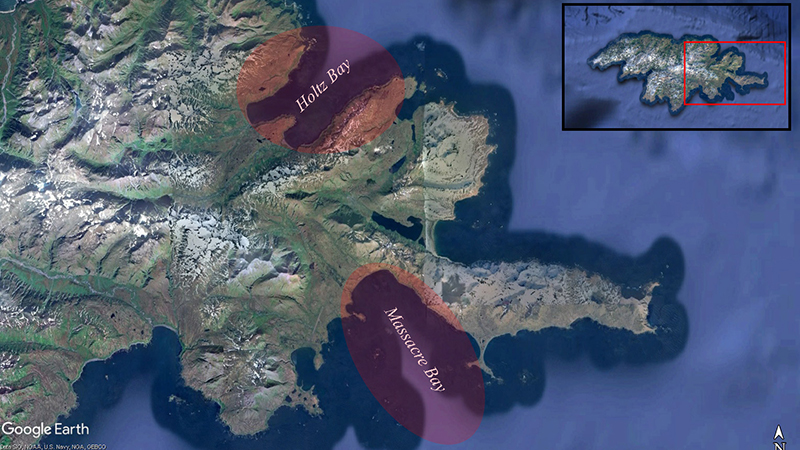

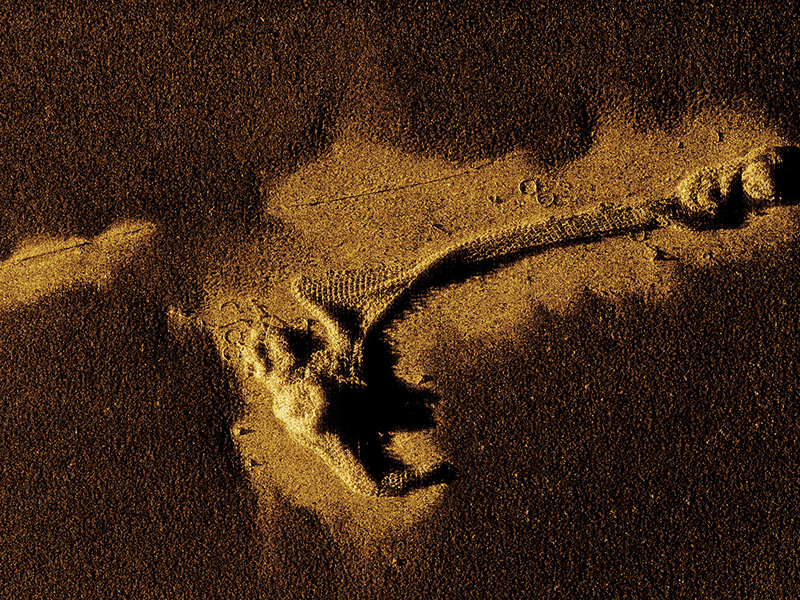

Subsequent survey work shifted to various locations within Massacre Bay, which served as the main landing site for the U.S. military during the Battle of Attu (1943), and later, became a hub for postwar military activity. While no wrecks were definitively identified in the field, the seafloor is littered with vestiges of World War II activity. This includes dozens of anchors, mooring blocks, and sunken buoys, as well as examples of materials used in the construction of infrastructure, such as timbers, piping, and cable. The immediate identification of these objects was made possible by the data’s resolution, demonstrating the benefits of SAS for underwater archaeology surveys. Perhaps the most interesting Massacre Bay find were the numerous examples of anti-submarine netting that could be clearly discerned. With the centimeter-scale resolution offered by SAS imagery, the interconnected metal rings of these nets, resembling chainmail armor, were seen in stunning detail. Often these harbor defenses were completely removed, as bays and ports returned to peacetime use. This does not appear to be the case, as the sunken net segments cover hundreds of meters of seafloor in Massacre Bay. Several targets were further investigated using the ROV, including a suspected landing craft. The photographic documentation revealed that this object was more likely a chassis, potentially for a flatbed trailer used in transporting construction materials. Here, the utility of combining acoustic (sonar) and optimal (ROV) imagery was made especially apparent.

The expedition also focused on areas in and around the West Arm of Holtz Bay, located to the northeastern side of Attu. Despite multiple reports of sunken airplanes and watercraft, the SAS surveys revealed a mostly barren, sandy seafloor. In both Holtz and Massacre bays, the overall lack of identified wrecks corresponding to smaller vessels, such as aircraft, landing craft, and barges, came as a surprise, given the combination of Attu’s notorious ocean conditions during the war and the high-level of sonar resolution the project team was using in the present day. This suggests that these wrecks have been more adversely affected by decades of water movement, storm activity, and sediment burial, as compared to larger surface ships.

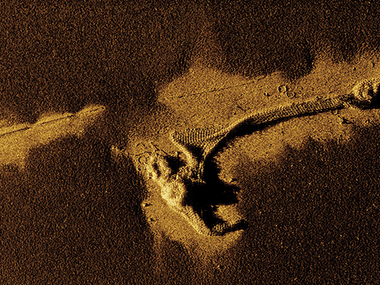

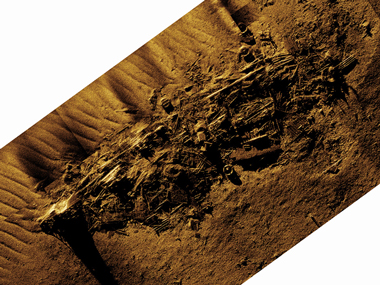

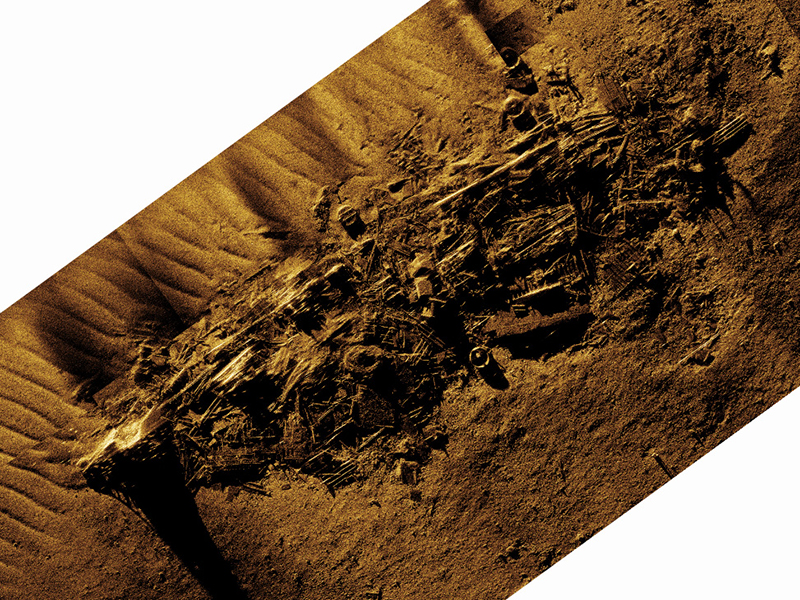

Further offshore, the research team explored deeper depths, mainly in search of Kotohira Maru, a 6,000-ton freighter carrying supplies from Japan that was bombed by an American weather plane on January 5, 1943. Prior to this project, there remained considerable debate as to how and exactly where this sinking took place, with many reputable secondary sources providing conflicting accounts. Despite war-era charts indicating its suspected location, the initial SAS surveys were unable to locate the doomed vessel. As such, the search area was increased, and after six hours of survey, the fairly-intact remains of Kotohira Maru were finally located in around 83 meters (275 feet) of water, over a kilometer from its last reported position. The high-resolution SAS imagery aligned perfectly with wartime records of this ship’s demise, demonstrating damage to the bow and starboard side. Structures such as the smokestack, masts, and counter stern were still upright in the water column, according to shadows seen in the sonar data. Once again, the ROV was deployed to make a visual confirmation of the wreck, which not only obtained photographic documentation of ship parts, but also revealed a rich benthic biota, largely dominated by anemones.

A second shipwreck of Japanese origins was located much closer to shore. Using the combination of an aerial drone and underwater ROV, the rusted remains of Cheribon Maru, a Japanese freighter sunk on Thanksgiving Day, 1942, by American aircraft, were observed. The ROV video revealed that the sunken shipwreck is host to a thriving community of kelp, making it difficult to identify individual vessel components. Unfortunately, the wreck site’s location in about 10 meters of water (33 feet) is beyond the minimal depth for sonar operations. The project’s success in locating the physical remains of both Kotohira Maru and Cheribon Maru is believed to mark a first in U.S. underwater archaeology. Unlike the Japanese shipwrecks at Kiska, which are clearly exposed above the sea surface, the Attu vessels are fully submerged, while their proximity to shore, as opposed to the aircraft carriers of Midway Island (Hawaii), means they are located within Alaska waters. This unique combination renders Kotohira Maru and Cheribon Maru the first Japanese World War II surface ships to be found completely under U.S. state waters. Both vessels are legally protected by the Sunken Military Craft Act (2004).

Images and Videos

Features

Meet the Explorers

Jason Raupp, Ph.D.

Principal Investigator

East Carolina University

Dominic Bush, Ph.D.

Co-Principal Investigator

East Carolina University

Caroline Funk, Ph.D.

Co-Principal Investigator

University at Buffalo

Alex Bolvin

Marine Surveyor

ThayerMahan, Inc.

Allen Collins

Marine Surveyor

ThayerMahan, Inc.

Education Content

Education Theme pages provide the best of what the NOAA Ocean Exploration website has to offer to support educators in the classroom related to this expedition. Each theme page includes expedition features, lessons, multimedia, career information, and associated past projects.

Related Links

Partners

Media Contacts

Emily Crum

Communications Specialist

NOAA Ocean Exploration

ocean-explore-comms@noaa.gov

Lacy Gray

Director of Marketing & Communications, Thomas Harriot College of Arts & Sciences

East Carolina University

grayl@ecu.edu

Funding for this expedition was provided by NOAA Ocean Exploration via its Ocean Exploration Fiscal Year 2022 Funding Opportunity and National Park Service’s American Battlefield Protection Program.

Published September 26, 2024