Exploring Attu’s Underwater Battlefield and Offshore Environment

Attu’s Wartime History

On June 7, 1942, in conjunction with the naval advance on Midway Island, the Japanese military landed on Attu (Atux̂) and quickly imprisoned the indigenous Unangax̂ population. The Aleutian natives were later sent to Otaru, Japan as prisoners of war (POWs), where they would remain for the duration of World War II. While Midway was an unmitigated disaster for Imperial Japan, Tokyo radio broadcasts presented the capture of Attu and nearby Kiska as a major victory. It marked the first time since the War of 1812 that a foreign power occupied United States soil in North America; a feat that has not since been repeated. The garrison on Attu quickly established fortifications on the island, while also initiating work on an airfield. American military leaders paid little attention to this threat, as action in the South Pacific, Europe, and North Africa constituted a more pressing matter. Towards the end of 1942, however, aerial missions to Attu began in earnest, with bombing and strafing runs designed to harass the foreign invaders and disrupt shipping efforts.

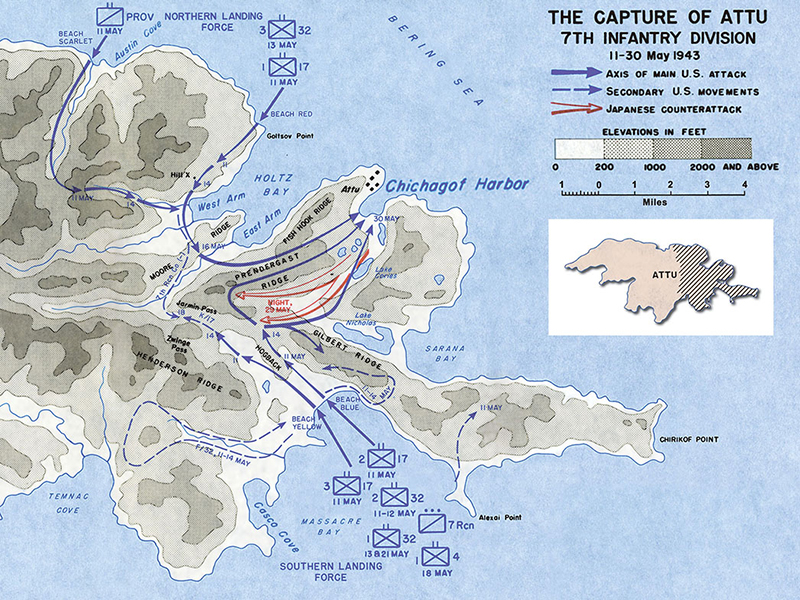

By the spring of 1943, following the defeat of the Axis powers in North Africa and further advances in the Pacific, the joint U.S. commanders decided that the Aleutians could no longer be ignored. They devised a plan that would start with the recapture of Attu, thus setting the stage for a larger invasion of Kiska. Inaccurate estimations of force size misled the U.S. military to believe that Attu was home to only 500 Japanese soldiers and that the island could be taken with minimal casualties. Furthermore, the American battle planners were woefully ill-informed about the exact nature of Attu’s rugged terrain and climate. When the Battle of Attu began on May 11, 1943, the 7th Infantry Division, with the aid of a U.S. Naval task force, executed the first amphibious assault for the U.S. army during the war. They were, however, unprepared for the sort of alpine warfare they were about to encounter. Additionally, the U.S. troops were met by a garrison of 2,500, not 500. These factors combined to prolong the battle from the estimated three days to three weeks. Over 500 U.S. soldiers perished, with several thousand wounded, mainly due to cold-induced injuries. The entirety of the Japanese force, apart from 29 POWs, died in battle. The U.S. troops on Attu were supported by both carrier-based naval aircraft and army aircraft launched from airfields further east. Predictably, numerous planes were lost, largely owed to bad flying conditions. While the first week of battle saw U.S. ships conduct dozens of shore bombardments, inclement weather worked to offset the effectiveness of naval gunfire.

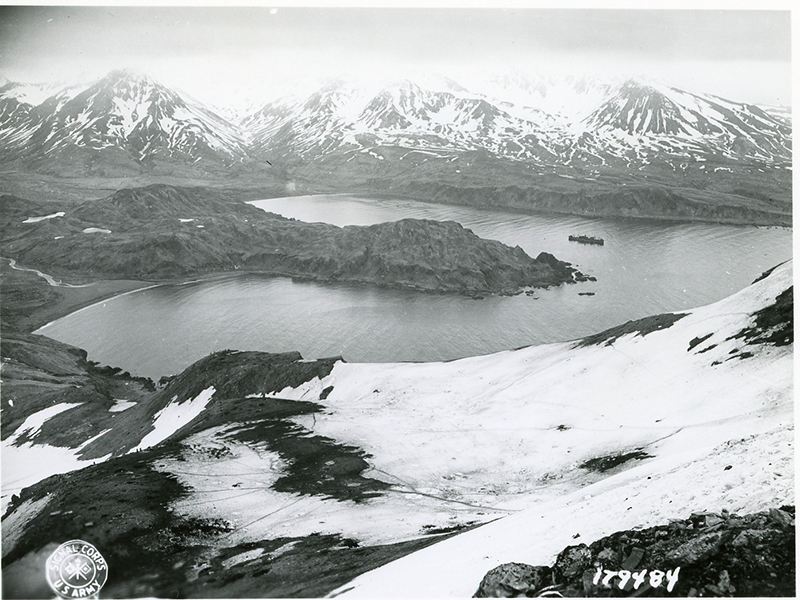

Concurrent with the final days of battle, the U.S. Army quickly began transforming the island into a military outpost, which included airfields, roads, fuel depots, and cargo piers. The Army’s Camp Earle, named after the fallen Colonel Edward P. Earle, was soon joined by the burgeoning Navy Town on the western shoreline of Massacre Bay. The island’s chief strategic importance was as an advanced weather base for installations further east, including those in mainland Alaska. Aerial raids on Japan’s Kuril Islands were also launched from Attu, though difficult flying weather limited the frequency in which these attacks could be made. Throughout the duration of the war, those stationed on Attu, both Army and Navy, were kept on alert for Japanese aerial and submarine raids, simulating responses through field exercises. Despite the threat of attack, the U.S. military continuously expanded its structural footprint on the island, as the number of stationed troops regularly exceeded 15,000. The greatest area of development concentrated in the Massacre Bay area, where the bay’s heavily-trafficked waters welcomed countless support vessels and cargo loads of base construction materials.

Archival evidence from 1942-1945 indicates that at least three Japanese ships (Cheribon Maru, Kotohira Maru, I-31) and three U.S. ships (SS Dellwood, SC-1067, ST-39) sunk around Attu, while over a dozen aircraft in total are reported as having crashed in the island’s waters. Smaller watercraft, namely mechanized barges used by the Japanese troops and landing craft participating in the U.S. landings and post-battle operations, are also believed to have wrecked at Attu. These vessels, both marine and airborne, symbolize a traumatic, yet forgotten period of history. The expedition team is using the latest in remote-sensing technology to locate these sites with the intention of offering the public an opportunity to reflect upon the sacrifices made by the combatants, as well as the transformation of the Unangax̂ ancestral lands into a military station.

By Dominic Bush, Ph.D.

Published October 16, 2024