Exploring Attu’s Underwater Battlefield and Offshore Environment

What's Next?

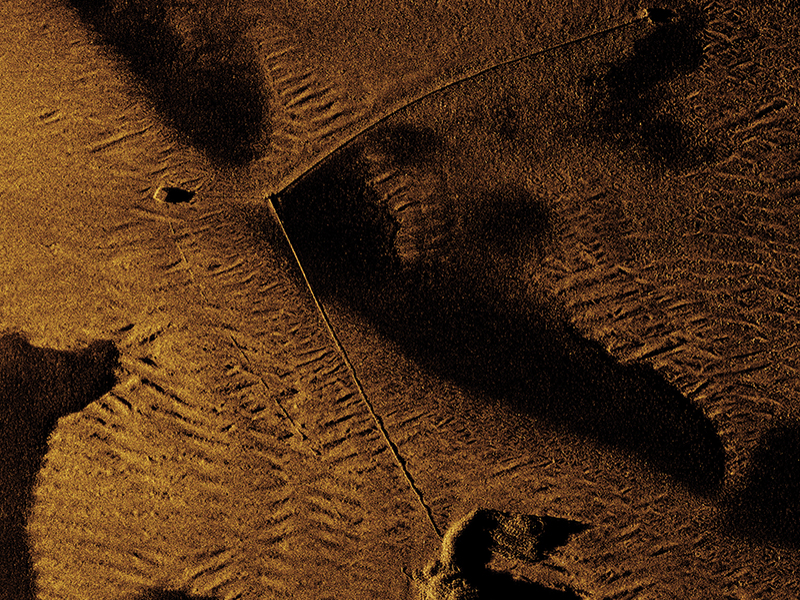

So, what is next? First, the research team will work with ThayerMahan staff on finalizing the synthetic aperture sonar (SAS) data. To create maps of surveyed seafloor sections, the geo-referenced sonar images will be combined and imported into Geographic Information System (GIS) software. The alignment of survey transects to reveal whole survey areas enables a better understanding of the spatial relationships between various targets. Debris scatters that at first glance looked innocuous can be more thoroughly considered, potentially revealing wreck sites that went unnoticed in the field. A potential wreck site has already been identified during the preliminary data analysis. A geospatial approach can also help researchers differentiate between targets of similar form but different uses, such as the 14 large ship moorings reported for Massacre Bay and those clearly used for anti-torpedo nets. Similarly, individual net segments can be viewed in relation to one another in an effort to retrace the harbor’s defenses. This analysis will of course include closer inspection of the imagery, possibly uncovering targets not seen within the sonar live feed.

Camera footage of the shipwreck sites obtained with the remotely operated vehicles (ROVs) will also undergo final processing to create more refined visuals that can be used for public outreach and interpretation. The ROV photographs and video will be thoroughly reviewed in conjunction with the sonar imagery in order to create archaeological site plans. As it concerns Kotohira Maru and SS Dellwood, individual ship components will be identified and mapped, allowing insights into what is and is not present. Results can then be compared to ship plans to see how each vessel’s construction was adapted to meet wartime needs. For Kotohira Maru, specifically, the research team is working with partners in Japan to search for archival documentation of the ship and its crew. Beyond locating the physical remains of Cheribon Maru, the project was limited in its ability to document this wreck site. The footage of the sunken freighter, however, will be reviewed by biologists interested in Alaska’s kelp populations. Likewise, the videos of Kotohira Maru and Dellwood offer the opportunity to not only characterize the benthic communities on each wreck, but also to evaluate how water depth and other environmental factors impact wreck ecology at Attu.

Future work is not limited to data analysis and scientific interpretation. The research team is working with several Alaska museums on designing potential exhibits featuring project data. Results will also be shared with educators in hopes of building school lesson plans that incorporate aspects of Attu’s World War II history and maritime archaeology. There has also been a concerted effort to be transparent with Alaska Native communities and share the project findings. While the data, both sonar and photographic, are informative from a research perspective, their utility is not purely academic. The destructive images of shipwrecks and the nearly frozen-in-time Massacre Bay seafloor bring a physical realness to Attu’s wartime past that may help bring awareness to this oft-forgotten chapter of history.

Published October 4, 2024