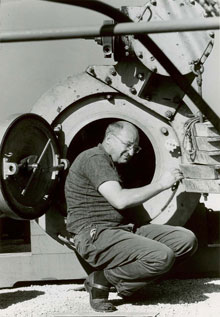

Figure 1. Edwin Link with one of his early submersibles. Click image for larger view and image credit.

Edwin Link and a Deep-sea Mystery

July 26, 2009

Erika RaymondMonterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute

When you slide into your car or step onto a plane, how often do you think about the person who engineered your mode of transportation? Crawling into the Johnson-Sea-Link (JSL) submersible, I paused to reflect on Edwin Link (figure 1), a visionary and an engineer who was behind the design and development of the JSL.

In the 1930s, Link first developed a flight simulator for pilot instruction, but Link's life-long passion was for the ocean. In 1961, late in his career, Link developed the Deep Diver submersible, which was the predecessor to today’s two Johnson Sea-Link submersibles – the JSL I and the JSL II. Fourteen tons of aluminum, high-density foam, acrylic, and cables make up the vehicle, designed to withstand tremendous pressure and carry deep-sea scientists comfortably and safely into the deep ocean to study this largely unknown environment. Link originally designed the submersibles to carry scuba divers to extreme depths, outfitting the subs with a decompression chamber behind the observation sphere.

Link was not driven by fame, fortune or ego, but rather by the most valuable tool an engineer or scientist can possess — curiosity. We thank you, Mr. Link, and the people you mentored. Because of your passion, we are able to pursue our own.

Figure 2. Crew members for the Johnson-Sea-Link and the research vessel Seward Johnson work in tandem for a successful launch/recovery of the submersible. Click image for larger view and image credit.

There are six JSL crew members who accompany the sub on the research vessel. They work in rotation to pilot, deploy, and recover the sub. Over the nine years I’ve come out to dive in these subs, I’ve observed the JSL's crew and ship’s crew perform a well-rehearsed and carefully choreographed "dance." It's one they’ve been conducting for so long that they behave like an old couple: each anticipating the other’s moves and, on occasion, bickering a little over the underwater communication link until a peaceful reunion is orchestrated at the surface (figure 2).

Dr. Edith Widder and I have worked with the Eye-in-the-Sea (EITS) camera system since 2004, and the JSL submersibles have been a major factor in its great success.

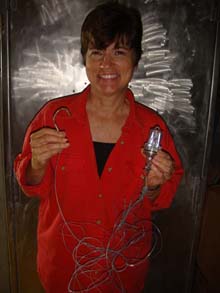

Figure 3. Dr. Edie Widder holds the mystery hook and lure found near the capsized Eye-in-the-Sea. Click image for larger view and image credit.

The Mystery Unfolds On the morning of Tuesday, July 21, the EITS was placed at a depth of 2,000 feet. It was equipped with a bait box to attract marine life, and its cameras set to record for one minute, every five minutes. For this deployment, the EITS would remain in place for several days, capturing the marine life going about their everyday business. That afternoon, the JSL descended again with other scientists and they noticed that the EITS was on its side and had been dragged for about 20 meters. Nearby, they spotted something and picked it up. It was a tangled mess of fishing line with a large rusty hook and an illuminating lure — still flashing (figure 3). Also swimming suspiciously nearby was a six-gill shark, a slow-moving, very large, deep-sea shark that "ambles" along the ocean floor. The pilot righted the EITS and they went back to the business at hand.

When we heard the tale, Dr. Widder and I were puzzled by the mystery of what caused the EITS to be knocked down and dragged away, and what this hook and line might have to do with it? Did a fisherman catch the EITS on its hook? Did that six-gill knock it down trying to get to the EITS bait box? Were the predatory pack of Cuban dogfish to blame?

What do you think happened? Submit your guess through our Ask an Explorer page. We’ll publish your responses right on the Ocean Explorer Web site. On Thursday, we’ll reveal the amazing footage that the EITS captured that solved the mystery.