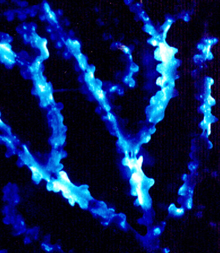

A luminescing bamboo coral. Click image for larger view and credits.

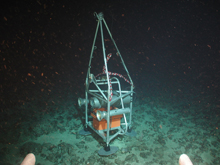

The Eye-in-the-Sea (EITS) in position at around 549 meters (1,800 feet) in the Gulf of Mexico. Click image for larger view and credits.

ORCA’s Eye-in-the-Sea

Edith A. Widder, PhD

President and Senior Scientist

Ocean Research & Conservation Association

To observe bioluminescence unobtrusively in different benthic (sea-bottom) habitats we will be deploying the Ocean Research & Conservation Association (ORCA) camera system, called Eye-in-the-Sea (EITS). This unique deep-sea observatory is an autonomous, battery-powered, video-capture and illumination system that uses far red light (which has the longest wavelength in the infra-red region), in combination with a highly sensitive camera that can record bioluminescence.

To observe nocturnal (nighttime) animals on land, investigators use invisible infra-red light and infra-red sensitive cameras. It's not so easy in the ocean. Infra-red light is absorbed too rapidly in sea water; it provides inadequate illumination of large animals, when used with standard infra-red sensitive cameras. To compensate for this, the EITS uses an exceptionally sensitive intensified camera. In addition, the illumination source, which is an array of light emitting diodes (LEDs), uses far-red light that travels further through seawater than infra-red light. This light is dimly visible to the human eye, but invisible to deep-sea dwellers that are adapted to see primarily blue light.

The camera and recording system are housed in a "bottle," a cylindrical can with an optical port, designed to withstand the crushing pressure at depths of up to 914 m (3,000 ft). (That's more than 1,300 pounds per square inch!) The light is mounted on a tripod, off-axis from the camera, in order to minimize backscatter from particles in the water. A lead-acid battery like those used in cars, but in an oil-filled pressure housing, provides the power.

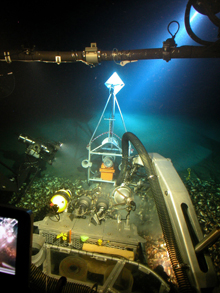

The EITS is positioned in a brine pool in the Gulf of Mexico. Click image for larger view and credits.

The EITS can be programmed to turn on its red light and record video at regular intervals. Alternatively, it can be programmed to record when its very sensitive light detector, called a photomultiplier tube, "sees" a bioluminescent flash. The flash triggers the camera to record three seconds of video with the lights out, in order to record the luminescence, and then turns on the red light to reveal the source of the light.

Deployments will be made using bait and/or an electronic jellyfish lure capable of imitating five different luminescent displays, including highly conspicuous "burglar alarm" displays. Burglar alarms are used by animals that are caught in the clutches of a predator. The alarm is similar to to a “scream” for help, except that it attracts the attention of a larger predator that may attack whoever is attacking "screamer," thereby affording them an opportunity for escape.

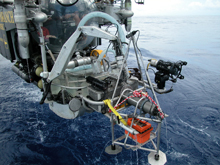

The Harbor Branch Oceanographic Institution/Florida Atlantic University Johnson-Sea-Link submersible is lowered into the water on its way to deploy the EITS. Click image for larger view and credits.

At the same time as our mission in the Bahamas, another newer version of the EITS will be streaming data back to shore in real-time from the depths of the Monterey Canyon. The battery-powered version of ORCA’s EITS has been the test bed for this new-and-improved version that is designed to go on a deep-water mooring that provides unlimited power. No longer limited to 48-hour deployments, the new EITS can collect data for months at a time and stream the video to the internet, providing the world’s first deep-sea Web cam (www.teamorca.org ![]() )

) ![]() .

.

It will be exciting to compare these two different views of the deep sea: one from a relatively low diversity region off the west coast in Monterey Canyon, and one from a high diversity region off the east coast in the Bahamas. Incredibly, we will actually have two windows into the deep sea at the same time. Windows that we hope will allow us to view animals, behaviors, and forms of bioluminescence never seen before.