Data Manager Susan Gottfried records information relayed from the submersible to Electronics Technician Jim Sullivan onboard the Seward Johnson. Click image for larger view.

Data Management: A Challenge, a Duty and an Honor

August 25, 2005

Susan Gottfried

Planning Systems, Inc./NOAA Coastal Data Development Center

“What the heck is that?” “Have you ever seen this before?” “What do you know about this?” Some of the questions I hear from the scientists on board our floating laboratory as they talk amongst themselves reveal that every day, they are making discoveries. They are true pioneers in the exploration of our deep ocean.

Web Coordinator Cindy Renkas takes photos and videotapes to include in daily logs posted on the NOAA Ocean Exploration Deep Scope Web site. Click image for larger view.

Before we steamed away from Harbor Branch Oceanographic Institution on the R/V Seward Johnson, I overheard a scientist say that when the submersible or sampling instruments are in the water, the images and specimens captured are only of the “slow or stupid” species. That made me smile to think that the “quicker or smarter” ones might conveniently slip out of the way when the humans are messing about. But with Dr. Edie Widder’s Eye-in-the-Sea (EITS) camera, she has found a way to entice them away from the sidelines and into her playing field.

I remember being around ten years old, sitting in front of our television set, watching the film footage from the lunar module as it slowly, weightlessly, navigated the moon’s landscape, capturing images that no one had seen before and emitting communication beeps back to mission control. Thirty years later, the feeling is the same. The submersible slowly, weightlessly, navigates the deep ocean landscape capturing images that no one has seen before and emits those same communication beeps back to mission control. The submersible pilot expertly maneuvers the robotic claw and suction hose over some of those “slow or stupid” species or fluorescing organisms attached to the bottomand collects them for the scientists anxiously ready to learn.

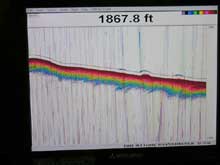

Transect depicting the bottom profile to determine likely submersible dive sites. The “fluffy” parts shown in this image are good potential Lophelia mounds on hard bottom on the Florida shelf. Click image for larger view.

Before the submersible dives, the ship’s captain and crew take bathymetry readings which generate a “picture” of the ocean bottom profile. (Figure 4 here) The scientists look for interesting bumps and other features that the submersible should target. Between submersible dives, the scientists dip or drag nets over the side to collect those tiny, invisible or cleverly concealed creatures that reside right under the surface or huddle among the fronds of the ubiquitous sargassum weed which floats by the boat. They examine their catch under powerful microscopes and log elaborate notes about them…and learn.

Meanwhile, the University of Miami marine technicians on-board the Seward Johnson constantly monitor such things as sea surface temperature and salinity, air temperature and relative humidity, wind speed and direction, precipitation, barometric pressure, solar radiation, and surface currents. While these data may not contribute to what these particular scientists are researching on this expedition, they will be important to someone else at some other time who is using this information...to learn.

Data Manager Lenny Collazo duplicates and maintains a library of all submersible and “blue water” scuba diving videotapes. Click image for larger view.

There are three of us representing NOAA’s Office of Ocean Exploration on this expedition. It is our job to document what is happening each day and to insure that the data, images and observations that are collected are catalogued, documented and archived so that anyone interested can discover them again and again and again.

We send daily logs and images to the oceanexplorer.noaa.gov Web site; copy the videos and still images to be archived at the NOAA Central Library; send the bathymetry data to be archived at the National Geophysical Data Center (NGDC); send the marine technicians’ data to be archived at the National Oceanographic Data Center (NODC); send navigation files for the ship and the submersible to be mapped in a Digital Atlas at the NOAA Coastal Data Development Center (NCDDC); and we make these data discoverable through web search engines for anyone to find….so that they, too, can learn more about our ocean planet.