The innovative Eye-in-the-Sea is a self-contained underwater camera system able to observe animals and their natural behaviors unobtrusively. It operates with red lights and an image intensifier that works something like night-vision goggles.

Eye-in-the-Sea: An Innovative, Unobtrusive Camera System

Mark Schrope

Science Writer

Harbor Branch Oceanographic Institution

The deep sea makes up about 78% of the planet's inhabitable

volume, but little is known about most of its inhabitants -- including those that can make their own light, or bioluminescence. This scientific deficiency

stems not only from

a lack of ocean exploration and study, but also

from less-than-ideal traditional research methods.

Some of these methods actually create problems, such as injury to specimens and/or interference with their natural behavior during research. Deep-towed

nets, for example, can shred animals, such as jellyfish, or damage captured animals

to the point that their natural behaviors cannot be observed in

the lab. Manned submersibles and remotely operated vehicles (ROVs) -- which are essential to deep sea research -- bring with them lights, motors, and electric fields that either scare animals away before

they're ever seen, or frighten them into unnatural behavior.

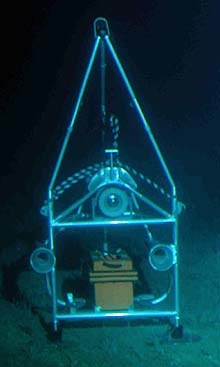

Dr. Edith Widder wanted a solution to these problems. She dreamed of, then created, an innovative, unobtrusive camera system to record life in the abyss. Called Eye-in-the-Sea, the system operates automatically on the sea floor. Most importantly, however, it is designed to go unnoticed by animals. The system uses bioluminescence to its advantage. It can detect animals nearby when they give off bioluminescent light, trigger a video camera to record the light being produced, then turn on a red light out of the animals' normal vision range. The result: the collection of illuminated footage, without alerting the subject or scaring it away.

The system can also be programmed to film surrounding

areas at scheduled intervals. (This feature will be useful, for instance, when Dr. Widder

and her team place the system on the bottom, along with bait to

attract animals). In the past, camera systems used on the sea floor

have relied on bright lights, which frighten those creatures accustomed to the

darkness of the deep.

Dr. Widder and her colleagues also developed Eye-in-the-Sea's ability to capture new

animals and behavior on film. A simple electronic device, deployed

with the system, mimics the various bioluminescent light patterns

given off by jellyfish, known as Atolla. Various Atolla species

are common in the deep sea; their round bodies, when viewed from above, look something like a tie-dye splotch. The artificial jellyfish lure is a disc, about six inches across, with a ring of blue LED lights around its outer

edge. The lights can be programmed to light up in patterns similar to those the jellyfish create.

How and why do jellyfish and other animals use their

bioluminescence?

Dr. Widder uses the lure to test hypotheses. For instance, jellyfish sometimes

respond to threat by creating a circular "wave" of light

around their outer edge that progresses like the lights on a movie marquee. Scientists call

this a "burglar alarm" response and theorize that jellyfish

use it to attract large animals in to eat whatever animal is attacking

the jellyfish. To test that theory and others, the

team deploys Eye-in-the-Sea next to a box of bait -- along with the artificial

jellyfish programmed to produce various displays -- to see how animals

in the area respond. The jellyfish lure can also attract large predators

to the area, which are captured on film.