Three live nautiliniellid worms, recovered on this cruise, in the mantle cavity of the clam. Image by J. Dreyer. Click image for larger view.

Discovery of a new species of polychaete worm at the Blake Ridge seeps

July 28, 2003

Jennifer Dreyer

Graduate Student

The College of William & Mary

Cindy Van Dover

Co-Chief Scientist

Windows to The Deep

The College of William and Mary

Biologists opening clams collected at the Blake Ridge cold seep in 2001 discovered that nearly every clam was occupied by one or more tiny, segmented worms. Not much is known about the mutual relationship between the worms with their host clam. We think that the worms do not harm the clams, and the clams provide the worms with a safe harbor from predators within their shells.

Scanning electron microscope (SEM) view of simple hooked chaetae in anterior segments. Image by J. Dreyer. Click image for larger viewx.

Scanning electron microscope (SEM) view of trifurcate chaetae in posterior segments. Image by J. Dreyer. Click image for larger view.

Cindy Van Dover preserved some of these clams and we studied their characters to determine if they were a new species. We knew immediately that they were polychaete worms, because polychaetes are defined by the presence of paired parapodia or “feet” running down the sides of the animal, one parapodium or foot per segment. Emerging from the parapodia are bristle-like chaetae that give polychaetes their common name of bristle worms.

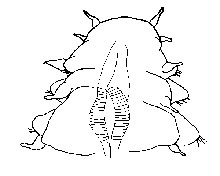

Dorsal (top) view of the anterior (front) end of the new nautiliniellid polychaete from Blake Ridge seep. Image by J. Dreyer. Click image for larger view.

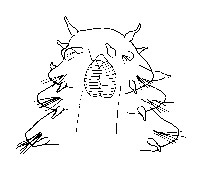

Ventral (bottom) view of anterior (front) end of the new nautiliniellid polychaete from Blake Ridge seep. Image by J. Dreyer. Click image for larger view.

The worms in the clams belong to a group known as the nautiliniellids, named for the French submersible Nautile that collected the first representatives of this group just over a decade ago. So far only 10 genera and 14 species have ever been described from this group, and all of them have been found living inside of bivalves at vents or seeps, often in very deep water. Clearly these are very special worms! Representatives in the group are found in the Gulf of Mexico as well as off the coast of Japan, and they are known from depths of about 100 m to almost 6000 m.

Scanning electron microscope (SEM) view of trifurcate (3-branched) chaetae on posterior segments. Image by J. Dreyer. Click image for larger view.

Nautiliniellids have a very simple body plan and few diagnostic characters. To tell one species from another, we rely on features such as minute appendages on the head and the number and types of chaetae on the parapodia.

Our Blake Ridge specimens were unlike any other described species. We collaborated with the world’s expert on this group of worms, Dr. Tomoyuki Miura at Miyazaki University, Japan, and prepared a description of our species. Read our documentation of the process of describing the species – take a look! (pdf document)

During dive 3910 of the Windows to the Deep mission, the pilot collected lots of clams for us, so he also collected lots of nautiliniellid worms. We brought our microscope and digital camera with us from our lab in Virginia, so we were able to take images of freshly collected specimens.

Live nautiliniellid worm, recovered on this cruise, removed from mantle cavity of the clam. Image by J. Dreyer. Click image for larger view.

The discovery of the new nautiliniellid species was only one of many firsts made on exploratory dives in 2001. With every new dive to the bottom of the ocean, we discover more and more new species. Exploration allows us to expand our knowledge of marine biodiversity and the range of lifestyles in extreme environments. Careful descriptions of newly discovered species are critical if we are to catalog and understand the diversity of life on our planet.

Chaetopterid polychaete removed from parchment-like tube. Golden hook is seen on the 4th row from the left. The large white curly objects coming off the head (left) are feeding appendages that sweep the surface of the sediments. This image was taken through a dissection microscope. Photo courtesy of J. Dreyer. Click image for larger view.

Tubeworms or worms in tubes? What is the difference?

Jennifer Dreyer, Graduate Student

College of William and Mary

One of our goals on this cruise was to answer the question “are tubeworms found at the Blake Ridge seep?” During the 2001 cruise to this site, images taken with the Alvin submersible showed patches of thin tubes emerging from the sediments. Biologists were unable to collect any of these animals in then. We planned to collect some of them on this cruise to determine what they are. Are they tubeworms or worms in tubes? This distinction may seem trivial and confusing, but to people who study polychaete worms, there is an important distinction. And even then, it is a distinction that is only most relevant for those who study worms located at hydrothermal vents or seeps where some animals have evolved symbiotic relationships with bacteria that help supply their nutritional needs.

At vents and seeps, “tubeworms” are worms that lack a functional gut and harbor bacteria in a special organ called a trophosome (in the middle region of the worm). The bacteria supply energy to the animal and allow it to grow. This relationship is special and provides the animals with a unique way to live in environments where there is no sunlight to fuel their energy demands through the process of photosynthesis. Tubeworms live in parchment-like tubes that they make themselves, and in which they can move up and down. There is a feathery-like structure called the plume at the head-end of the animal. The plume is bright red and is an area of gas exchange. Tubeworms typically grow in dense aggregations and anchor themselves to rocks on the bottom or in the sediment.

Riftia tubeworms, mussels, and scavenging crabs found at the hydrothermal vent site East Wall, located at 9° North on the East Pacific Rise. Photo courtesy of C. Van Dover. Click image for larger view.

“Worms in tubes” are “normal” polychaetes. These worms build tubes that they use as a home, but they have functional guts and typical feeding behaviors. They do not have the symbiotic bacteria in their bodies. They can grow in dense aggregations, but it is also common for them to maintain a distance from other individuals. There are a variety of different types of worms that live in tubes and they each have a distinct look. Even the tubes can vary in size, shape, material, and length.

We wanted to determine what type of worm in tubes lives in the Blake Ridge seep sediments. Efforts to sample these individuals were not especially successful. Evenly spaced tubes along the bottom that were documented in 2001, and seen again on this trip, have been sampled but are too fine to be dissected under a dissecting microscope. Other worms in tubes collected on this dive series, especially from within the mussel beds, appear to be worms in tubes. After examination under the dissecting microscope and removal of the tubes, the worms were identified to the polychaete family Chaetopteridae. These worms have a distinct look and were easily identified once we saw the characteristic modified hooks on the feet of segment 4 of the body. The location of these hooks is different in other polychaetes.

The question of whether there are tubeworms at Blake Ridge remains unanswered. During this expedition, there was an observation of two small aggregations of worms in tubes that were not seen in 2001. These aggregations seem more characteristic of tubeworms, although we have no conclusive evidence one way or the other. The answer will have to wait until another cruise returns to explore the hidden secrets of what this amazing seep has to offer.