This large sea fan Plumarella pourtalessi expands a basketstar in the current to capture plankton. Photo: John Reed. Click image for larger view.

What’s in a Name - Coral Reef?

John K. Reed

Harbor Branch Oceanographic Institution, Division of Biomedical Marine Research

Senior Research Scientist

Deep-water coral reefs, also referred to as bioherms, coral banks, or lithoherms, typically consist of thickets of live coral, capping mounds of unconsolidated sediment and coral rubble, and are often built upon an underlying rock base structure. Deep reefs usually are found in regions of fairly strong currents or zones of upwelling. The coral structures capture suspended sediment and build up mounds to heights of a few meters to 150 m (492 ft). Corals are found at average depths of 70 m to 1,000 m (230 to 3,280 ft). At these depths, the corals lack zooxanthellae, the algal symbiont found in shallow, reef-building corals. However, the deep-water reefs still provide habitat for thriving and diverse reef communities.

Oculina varicosa coral forms massive colonies over 1 m in diameter at depths of 200 to 300 feet. Photo: John Reed. Click image for larger view.

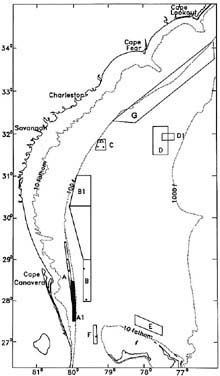

Two Types of Deep Reefs

Two types of deep-water coral reefs—Oculina and Lophelia—occur off the coast of the southeastern United States, primarily between Florida and North Carolina. The geomorphology and functional structure of both the Oculina and Lophelia reefs are similar, but they occur at different depths. The deep-water Oculina coral reefs form an extensive reef system at depths of 70 m to 100 m along the shelf edge off the coast of central eastern Florida. These reefs are comprised of numerous pinnacles and ridges, and range from 3 m to 35 m in height. Each pinnacle is a bank of unconsolidated sediment and coral debris that is capped on the slopes and crest with living and dead colonies of Oculina varicosa, the ivory tree coral. These reefs were studied during NOAA’s Islands in the Stream 2001 Expedition. In comparison, deep-water reefs of Lophelia pertusa corals occur at depths of 500 m to 850 m and form pinnacles up to 150 m tall along the base of the Florida-Hatteras slope in the Straits of Florida. On the western edge of the Blake Plateau off South Carolina and Georgia, banks that reach 54 m high of Lophelia occur at depths of 490 m to 550 m. On the eastern edge of the plateau, the reefs form structures 146 m high and at depths of 640 m to 869 m.

These specially designed traps isolate the shrimps and crabs inside from light and elevated water temperatures as they are brought to the surface. Click image for larger view.

Coral Description and Distribution

In deep water (more than 60 m), Oculina varicosa forms spherical, bushy colonies that are 10 cm to 1.5 m in diameter and height. The branches average 6 mm in diameter near the tips and frequently fuse together. Individual corals may grow together to form linear colonies 3 to 4 m in length, or they may form massive thickets of contiguous colonies on the slopes and crests of the deep-water reefs. The deep-water Oculina varicosa lacks zooxanthellae and is white. In shallow water, however, Oculina varicosa is usually golden brown because it is infused with the algal symbiont. The shallow-water colonies average 30 cm in diameter, with thicker branches, but they do not form thickets or coral banks like the deep-water form.

Similar in gross morphology to Oculina, Lophelia pertusa coral also forms massive, bushy colonies, 10 cm to 150 cm in diameter, with branches that may grow together. It is distributed throughout the western Atlantic from Nova Scotia to Brazil and the Gulf of Mexico, and also in the eastern Atlantic, Mediterranean, Indian, and eastern Pacific Oceans at depths of 60 m to 2170 m.

A deep-water sponge Pachastrella monilifera is found on the Lophelia coral reefs. Photo:HBOI. Click image for larger view.

Coral Growth and Reef Age

Oculina varicosa occuring at a depth of 80 m grows an average of 16 mm per year. At this rate a large, 1.5-m-high colony may be nearly a century old. Lophelia pertusa have shown comparable growth rates of 6-25 mm per year. Both types of reefs are found in areas of upwelling along the shelf edge. Thus, it is likely that the upwelling of nutrient-rich water onto the shelf and subsequent increases in plankton may enhance the growth of the coral.

Using radiocarbon dating techniques, dead Lophelia reefs in the Gulf of Mexico were estimated to be about 40,000 years old. Dead Lophelia from the Straits of Florida were dated at 28,170 years. Likely, these Oculina reefs were exposed about 15,000 years ago during the height of the Wisconsin glacial period, when the water stand was extremely low. Radiocarbon dating has helped us estimate that these current Oculina reefs began to form about 980 years ago, which makes them relatively young.

This large fan-shaped sponge Phakellia ventilabrum grows to 3 feet wide. It always faces into the prevailing current. Photo: HBOI. Click image for larger view.

Deep-water Coral Reef Communities

The deep-water coral reefs support very rich communities of associated invertebrates and fish. Faunal diversity on the Oculina reefs is very high—equivalent to many shallow-water tropical reefs. More than 20,000 individual invertebrates were found living among the branches of 42 small Oculina colonies from deep and shallow water, yielding 230 species of mollusks, 50 species of decapods, 47 species of amphipods, 21 species of echinoderms, 15 species of pycnogonids, and numerous other taxa. One striking difference between the Oculina and Lophelia reefs is that larger sedentary invertebrates such as massive sponges and gorgonians found on the Lophelia reef are not common on the deep-water Oculina reefs. Rather, the Oculina coral itself is the dominant component on these reefs.

The Lophelia reefs support large populations of massive sponges and gorgonians in addition to the smaller macroinvertebrates which have not been studied in detail. Dominant macrofauna include large plate-shaped sponges and fan-shaped sponges that grow to over 1 m.

This gorgonian Eunicella is common on the deep-water Lophelia coral reefs. Photo: John Reed. Click image for larger view.

Human Impacts

Bottom trawling and dredging can cause severe damage to these deep reefs, as indicated on deep-water Oculina reefs off the coast of Florida, Lophelia reefs off Norway, and deep-water seamounts off New Zealand and Tasmania. During NOAA’s Islands in the Stream 2001 Expedition, researchers documented extensive damage apparently from shrimp trawling on the Oculina reefs. Moreover, the Institute of Marine Research of Norway has documented severe damage to the Lophelia from shrimp trawling. In addition, most deep-water fish stocks are overfished or depleted in these areas. Because most benthic fisheries focus on apex predators such as groupers, snappers, and sharks, removal of these predators and other ecologically important species may have severe long-term repercussions to the fisheries.

This large fan-shaped sponge Phakellia ventilabrum grows to 3 feet wide. It always faces into the prevailing current. Photo: HBOI. Click image for larger view.

Deep-water Coral Reef Marine Protected Areas

The deep-water Oculina reefs were the first deep-water reefs in the world to be designated as a Marine Protected Area (MPA). A 92 sq.-mile Oculina Habitat of Particular Concern (HAPC) was designated off the coast of Florida in 1984 and was expanded to include 300 sq. mi. in 2000. Meanwhile, the need to protect other deep-water reefs has gained worldwide attention. Recently, Norway designated its first MPA—the first MPA to protect deep-water Lophelia coral reefs. In Canadian waters, the Northern Coral Forest MPA has been proposed for deep-water, soft coral habitats off Nova Scotia. A deep-water marine reserve was established in 1995 on the continental shelf south of Tasmania over an area of 370 sq. km. It protects 14 deep-water seamounts that are known to be highly diverse but limited to that region. In fact, up to 43 percent of the Tasmanian seamount fauna are new to scientists, and up to 33 percent are restricted to this environment.

Future of Deep Water Reefs

Because most MPAs are so remote and far away from the coast, it is extremely difficult to patrol and enforce restrictions within them on a 24/7 basis. However, random surveillance by spotter planes and enforcement vessels may discourage the major offenders. Educating the commercial and recreational fishing communities about the importance and delicate nature of these rich resources is also important. This will lead to better self-regulation and surveillance by the fishing community itself. Only by sharing knowledge of these deep-water coral reefs with the public through videos, photos, and educational efforts will we gain their understanding and acceptance of the need to protected these important resources.

Sign up for the Ocean Explorer E-mail Update List.