![]() Even in the harsh environment of the deep ocean, life is still visible. Click the image to watch a video of deep-sea life on the Galapagos Rift. (mp4, 723 KB)

Even in the harsh environment of the deep ocean, life is still visible. Click the image to watch a video of deep-sea life on the Galapagos Rift. (mp4, 723 KB)

Exploring “Rose Bud”

May 28, 2002

![]() Click to watch a video of deep-sea life on the Galapagos Rift. (mp4, 723 KB)

Click to watch a video of deep-sea life on the Galapagos Rift. (mp4, 723 KB)

ABE again proved its worth, and the benefits of autonomous vehicles. During the night, ABE surveyed much of the operating area looking for temperature anomalies, sure indicators of hydrothermal venting. During the day, Alvin dove with Chief Pilot BLee Williams, Susan Humphris of WHOI, and Capt. Craig McLean, Director of NOAA's Ocean Exploration program. This was McLean's first dive in Alvin. See what kind of initiation that brings in the essay below. During the day, the Alvin team received a telephone call from NOAA's Deputy Under Secretary, Scott B. Gudes, who wished the team and the exploration expedition well. During the dive, the Alvin team surveyed and mapped a new hydrothermal vent community discovered during the expedition, dubbed “Rose Bud,” in reference to the seeming disappearance of the original Rose Garden community originally found in 1979, and last visited briefly in 1990. It was the Rose Garden site that lead biologists to the rich discoveries of diverse communities of chemosynthetic organisms, revolutionizing our collective understanding of life on earth.

Capt. Craig McLean enters Alvin for Dive #3790, on May 28, to 2450 meters of water. The dive mapped a hydrothermal vent community discovered the previous day on a dive by Co-Chief Scientists Steve Hammond and Tim Shank. Click image for larger view.

A first dive on Alvin.

By Capt. Craig McLean, Director, NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration

After 30 years of diving on scuba, hardhat, and other submersibles, I found myself in the titanium sphere of Alvin, headed down nearly a mile and a half beneath the sea. This was my first dive in Alvin. Is the excitement and scientific promise of this journey stale because of the many who have gone before me on this vessel, and made such significant discoveries? Not at all!

Our scientific diving preparation begins days before with an orientation to the safety equipment, release and rescue procedures, and an introduction to the interior of the submersible, or submarine. Our Alvin crew, led by Chief Pilot BLee Williams, refers to Alvin as a submarine, and so will I. Once we familiarize ourselves with the interior of the sub, it's time to learn about the mission gear. We will be responsible for taking photographs of bottom features, logging the scientific data collected, and conducting two complex sampling procedures with special gear mounted to the front of Alvin. One experiment collects gas-tight water samples from the hydrothermal vents, and the other measures the temperature of the vents at their source. Both of these readings and samples will help further define the ideal growing conditions in which the diverse organisms of these vent communities survive, or perhaps, thrive.

On dive day, May 28, the ship has already been working through the night with CTD tows, camera sled tows, and ABE deployment. I'm growing fond of ABE as a very productive and efficient autonomous mapping machine. Before we leave for the dive, Dr. Dana Yoerger of WHOI provides us with fresh maps of the bottom, where ABE has detected elevated temperatures (areas in which we will want to direct our explorations) and showing areas of normal temperature. And so, just before 0800, into the sub we go. In addition to Chief Pilot BLee Williams and me, Dr. Susan Humphris of WHOI is diving. We kick off our shoes and head down the hatch. While the sphere seems small at first, it gets quite comfortable for three people-three very close and patient people. The sub is launched quickly, and the movement of the sea is quickly felt as Alvin is placed in the water. The ride down takes about an hour and a half. Or so says my watch. It does not seem that long. During the trip we put on extra layers of clothing. It is cold on the bottom, about 4 degrees Centigrade outside, just a bit higher in the sub.

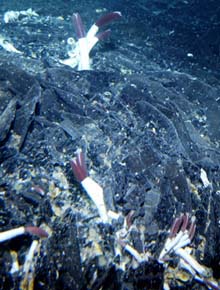

Tubeworms at the Rose Bud site, found during the early phase of this expedition. The worms are stout, with a base of almost three centimeters in diameter, but not taller than a meter length. Photo: C. McLean Click image for larger view.

With the bottom in sight, I quickly forget the brief glimpses of bioluminescent creatures we encounter during our descent, and I look out of my starboard viewport through its 4-inch thick Plexiglas. In shades of blue and black, the bottom develops like a black and white print. Then, white objects appear scattered on the bottom. This is a good sign. Much of the life we are looking for is white: tube worms, crabs, mussels, and clams. The pilot ballasts Alvin allowing us to hover, and we begin to examine a vent community discovered yesterday by Steve Hammond and Tim Shank. Because we have lost a thruster to an electrical ground problem, our steering will be more complicated, require more electricity, and potentially reduce our dive time. We quickly settle into the vent field and explore its perimeter. The Alvin navigation system, and skilled piloting by BLee, enables a photosurvey of the area, which takes most of our dive time, and is very important. A photomosaic from this survey will establish a baseline biological inventory and site map for any future study. We will also find that ABE and Dana Yoerger's team has produced a contour map to 0.5 meter resolution. This united effort defines exploration, and I was elated to be a part of it. Find something new, describe it, then map and inventory it for the use of future scientific study.

After our survey effort, we settle into an area and collect biological samples including tube worms, mussels, and two small clams. On each of these are additional assortments of limpets, worms, and other invertebrates. Who knows what kinds of bacteria will be isolated from these samples. Our biology team will be very busy into the night separating and working up the samples. These vent communities are not fully inventoried, and clearly not often visited. Collections are important. We also conducted water chemistry work, collecting vent water in specially designed gas-tight cylinders (to prevent dissolved gases from escaping) for Dr. Eric Olson of the University of Washington, and temperature readings from the vents for Dr. Kang Ding, of the University of Minnesota. As we approach the end of the dive, BLee settles the Alvin and begins the delicate process of collecting two small clams, which his experienced eye has located in a small fissure of lava. The mechanical manipulator arms will be guided by his maneuvers of the control device, just inches away, and thousands of pounds of pressure away, inside of the sphere. As this sample takes place in front of the sub, I look out at the still life scene just beyond my starboard view port. The port is only four inches wide but I see a world beyond it. The area is somewhat spotty with tube worms, not like the complete coverage originally found at Rose Garden. I am taken by surprise by the richness and diversity of creatures that inhabit the bottom, just outside by view port. Small invertebrates abound, concentrated in and around this chemosynthetic community. Feather dusters, as they are called, and some anemone-like stalks with tentacle protuberances, are more closely related to the Portuguese Man-o-War, Dr. Humphris reminds me.

Captain Craig McLean takes the Alvin initiation plunge, front and center. There is no easy way to take an ice water bath, an initiation rite for first time divers in Alvin. Does anyone have a towel? Click image for larger view.

As I look at the tube worms, I see the most visible and perhaps the best-known representatives of these unique communities. These small creatures remind me that the more we look, the more we find.

Alvin leaves the bottom on schedule. Another hour and a half transit, this time up. We stow our cameras, data sheets, and eventually shed our extra layers of clothing. At 400 meters, light begins to penetrate outside the sphere. At 100 meters, the exterior light almost seems brilliant, like the surface sun, after the darkness of the deep sea. But at 20 meters, the feeling of the surface surge reminds me that we are almost afloat and soon we are back aboard, hatch opened, and greeted by the science party and crew. As I descend the steps leading from Alvin to the main deck, Pat Hickey reminds me, “no running.” This is not an expression of simple pool etiquette; this is a warning. I'm in for an initiation that I can't evade. In fact, the ice water initiation, like the dive experience, is worth taking front and center. And I did both.

Sign up for the Ocean Explorer E-mail Update List.