Dr. Rhian G. Waller, University of Maine

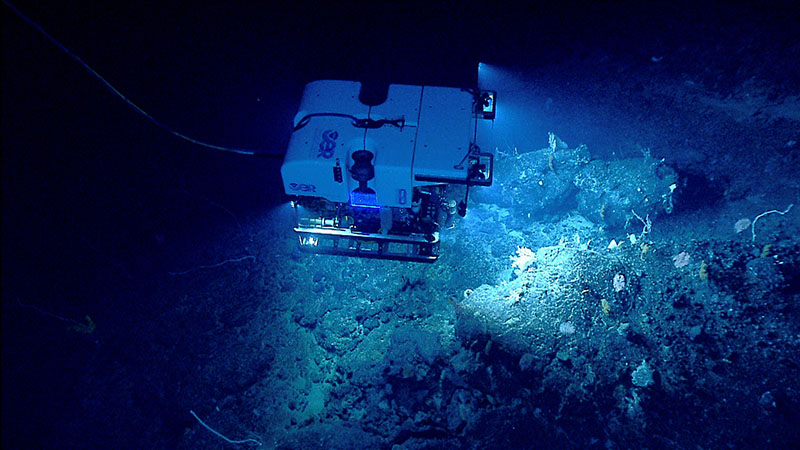

Remotely operated vehicle Deep Discoverer exploring deep-sea corals and sponges on Retriever Seamount during a 2014 expedition to the Atlantic Canyons and Seamounts. Image courtesy of NOAA Ocean Exploration, Our Deepwater Backyard: Exploring Atlantic Canyons and Seamounts 2014. Download largest version (jpg, 1.6 MB).

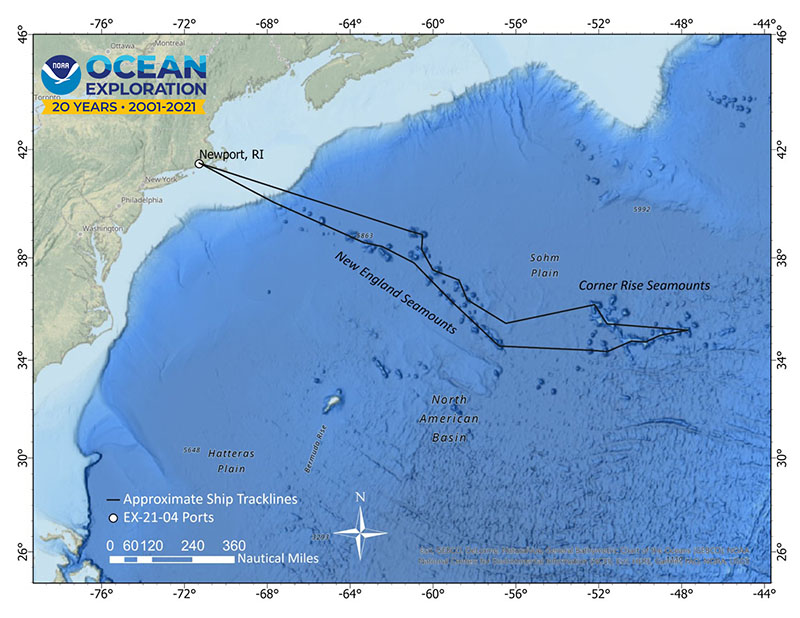

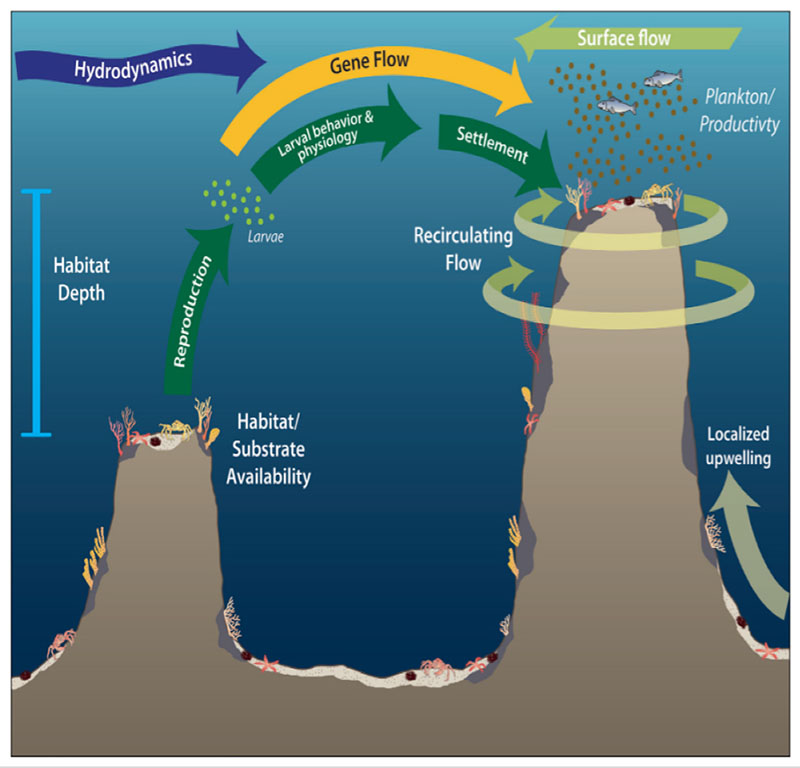

Some seamounts are isolated places, sticking up from abyssal depths and surrounded by vast plains dominated by sediments, many hundreds of miles from any other significant seafloor feature. But others, like New England and Corner Rise, formed long chains as the continental shelf glided over a hotspot in the Earth’s crust, creating seamounts one after another in a long succession stretching back over 100 million years. Though both of these types of seamounts interrupt the flow of cold, deep waters, bringing nutrients to the surface which feed intense surface plankton blooms that in turn die and sustain abundant deep-sea life, seamount chains can do something more.

Map showing the two seamount chains we will visit during this cruise - the New England and Corner Rise. Map courtesy of NOAA Ocean Exploration, 2021 North Atlantic Stepping Stones: New England and Corner Rise Seamounts. Download largest version (jpg, 600 KB).

These seamount chains can form what we call “stepping stones” across the seafloor—areas of habitat that are suitable for a wide variety of species to settle, colonize, and live. Just like a stepping-stone pathway in our garden, where each stone is placed at just the right distance for our feet to fall on, these seamounts can provide ideal habitat that is just the right distance away for larvae to travel and settle. One single seamount alone can become a hotspot of biodiversity, an area with many species living and thriving together. But a chain of seamounts can increase the chances of larvae settling by having even more suitable habitat available than just a single peak, potentially increasing overall biodiversity in a wider ocean region.

Whether species can colonize from one seamount to another is very dependent on what distances they or their larvae can travel and how the ocean currents flow along the chain. For example, if the current is pushing in one direction, small larvae are unlikely to be able to swim against it to settle in the opposite direction, at least not on a regular basis. It’s also important to note that ecological stepping stones are not a concept confined to the ocean. Up here on land, having patches of habitat suitable for a wide range of species close to each other creates refuges and helps increase biodiversity in an ever-more human-modified planet.

Diagram showing deepwater upwelling, caused by nutrient-rich bottom-water hitting the seamounts and circulating around them, and potential flow of larvae from one seamount to another. Image courtesy of Shank 2010, Oceanography; Morrison et al. 2015. Download largest version (jpg, 308 KB).

We know from deep coral species that sometimes we see corals that inhabit many seamounts along a chain, while for other species, we see them colonize just one or a small handful. Genetic studies also show links between seamounts for some species, and yet sometimes when we see the same species on more than one seamount in a chain, they are not genetically linked, meaning the larvae are not settling along that pathway.

We have yet to understand the basic biology of these deep-dwelling corals to fully understand just why that is, but one of the first steps to understanding how these stepping stones work is to explore and see what is there. So, as we tiptoe across the deep North Atlantic and back, seamount by seamount, it will be exciting to see what species are shared, and which are unique, to each of these stepping stones.

Published June 23, 2021