The 2021 North Atlantic Stepping Stones: New England and Corner Rise Seamounts expedition didn’t start off quite as planned, as weather pushed NOAA Ship Okeanos Explorer far south of the originally targeted exploration area and the first three expedition dives took place on neither the New England nor Corner Rise Seamount Chains. Thankfully, the weather cleared and we were able to conduct eight successful dives actually on seamounts within the Corner Rise chain.

As we transition to our next set of dive sites on the New England Seamounts (mapping along the way, of course!), we asked our expedition team leads what was most interesting, most surprising, or aspect from which they learned the most during our eight dives on the Corner Rise Seamounts. Their responses are below.

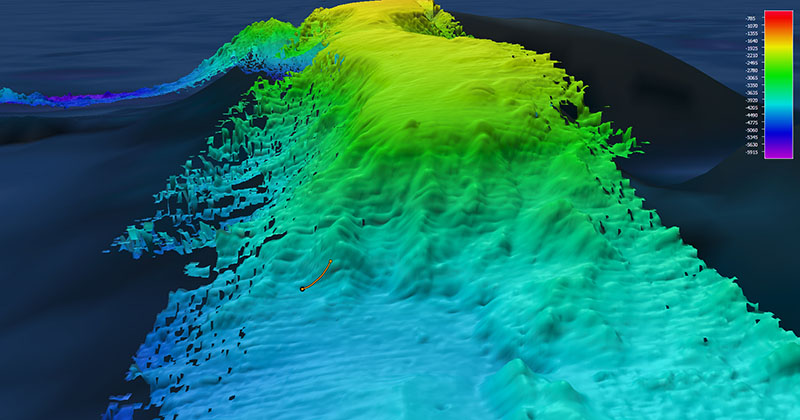

Multibeam bathymetry showing a perspective view of Rockaway Seamount (looking north), which was explored during Dive 05 of the 2021 North Atlantic Stepping Stones expedition. Image courtesy of NOAA Ocean Exploration, 2021 North Atlantic Stepping Stones: New England and Corner Rise Seamounts. Download largest version (jpg, 937 KB).

My favorite part about our time in the Corner Rise Seamounts was how we were able to make complete use of the operational capabilities of NOAA Ship Okeanos Explorer. Several days were what we call “map and dive” days — this means that up until the hours immediately before the dive, we didn’t have mapping data over our dive site. So within a few hours, we were able to go from a site being completely unmapped to having remotely operated vehicles on the seafloor, sharing the first-ever observations from that seamount. It’s a pretty impressive evolution that involves collecting valuable information that will help to close some of the data gaps in the region. It’s even more rewarding when what we find on the seafloor turns out to be a biologically diverse community or when we see something unexpected, like a dumbo octopus!

This rock sample was collected during Dive 09 of the 2021 North Atlantic Stepping Stones expedition dive on Yakutat Seamount. After recovering the sample, it was determined to be a nummulite agglomeration. Nummulties are large single-celled organisms called foraminifera with a characteristic coil shape. Image courtesy of NOAA Ocean Exploration, 2021 North Atlantic Stepping Stones: New England and Corner Rise Seamounts. Download largest version (jpg, 1.5 MB).

A magnified image of the nummulite agglomeration sample collected during Dive 09 of the 2021 North Atlantic Stepping Stones expedition. In the image, the lens shape of the fossilized nummulites is clearly visible. This sample will help scientists better determine the age and understand the history of the Corner Rise Seamount Chain. Image courtesy of NOAA Ocean Exploration, 2021 North Atlantic Stepping Stones: New England and Corner Rise Seamounts. Download largest version (jpg, 1.6 MB).

The dives on the Corner Rise Seamounts provided some of the first opportunities ever to explore seafloor features that have not been mapped or seen, which is always a special experience. The numerous observations of carbonate caps on these seamounts, and the collection of samples (most importantly the nummulite agglomeration sample) that will help reveal the early history of these features, perhaps when they were at or above sea level, has been the highlight of the expedition so far.

A multispecies coral garden, shown here on an outcrop ledge, was discovered during Dive 11 of the 2021 North Atlantic Stepping Stones expedition while exploring the eastern part of Caloosahatchee Seamount. Image courtesy of NOAA Ocean Exploration, 2021 North Atlantic Stepping Stones: New England and Corner Rise Seamounts. Download largest version (jpg, 1.4 MB).

Being able to contribute to the scientific understanding of the Corner Rise Seamounts through the data collected in the region has been a great opportunity. It was amazing to see transition zones in the geomorphology of the region (from basalt to carbonate caps and seamounts to guyots) as well as the phases of minimal observations of biology that then transitioned into sponge gardens leading to coral gardens.

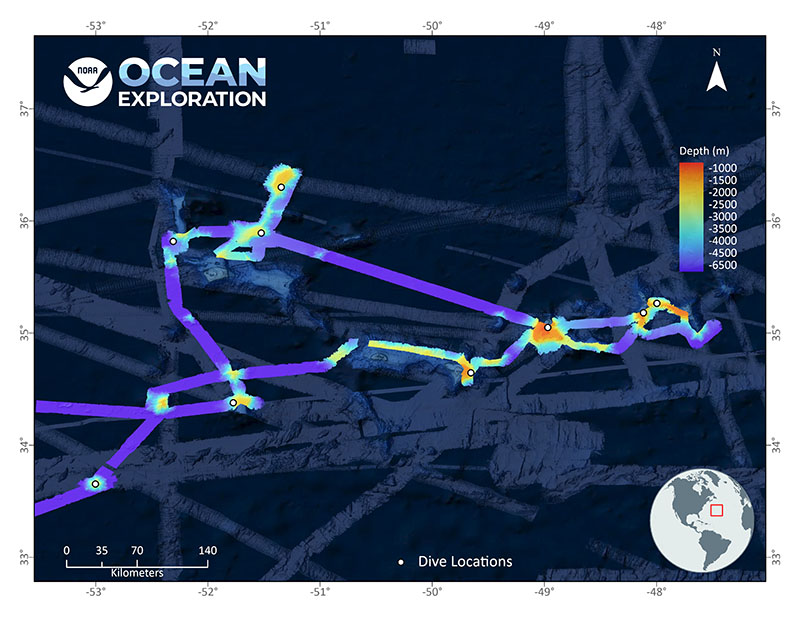

Map showing the bathymetric data collected around the Corner Rise Seamounts during the 2021 North Atlantic Stepping Stones expedition. Much of this area had not been mapped at all prior to the expedition, and in addition to providing critical information needed to successfully plan expedition dives, this mapping data contributes to our overall understanding of the seafloor. Map courtesy of NOAA Ocean Exploration, 2021 North Atlantic Stepping Stones: New England and Corner Rise Seamounts. Download largest version (jpg, 6.5 MB).

As the mapping lead for this expedition, it was very exciting to close gaps in our collective knowledge of the seafloor morphology in such a fascinating and remote region. Additionally, it was interesting to compare advancements in technology when remapping a location and discovering finer details of previously mapped features.

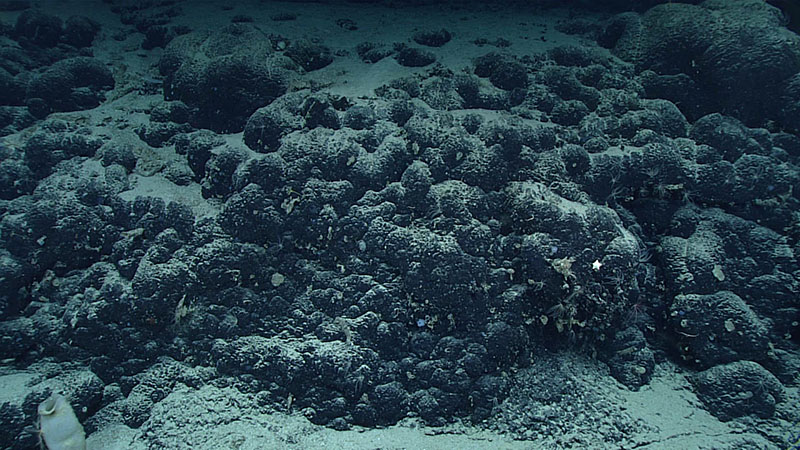

The bubble-like landscape imaged during Dive 06 of the 2021 North Atlantic Stepping Stones expedition dive on Castle Rock Seamount. Image courtesy of NOAA Ocean Exploration, 2021 North Atlantic Stepping Stones: New England and Corner Rise Seamounts. Download largest version (jpg, 1.5 MB).

As a scientist who studies marine minerals, my favorite dive from the Corner Rise Seamounts was Dive 06 on Castle Rock Seamount. During this dive, we saw thick ferromanganese crusts with very large botryoids (a rock textural feature that looks like a bunch of grapes) coating pillow lavas to create a wonderful bubble-like landscape. I also learned that the freshest, or most recently forming, ferromanganese crusts were observed during our dives to Corner Rise Seamounts in water depths between 2,000 and 2,500 meters (6,562 and 8,202 feet), which gives us clues about sedimentation, currents, and water masses over the long history of this seamount complex.

Several crinoids were seen living in the branches of a primnoid octocoral during Dive 08 of the 2021 North Atlantic Stepping Stones expedition. Animals like corals and sponges often serve as “ecosystem engineers,” building habitats for other organisms. Image courtesy of NOAA Ocean Exploration, 2021 North Atlantic Stepping Stones: New England and Corner Rise Seamounts. Download largest version (jpg, 1.3 MB).

During the eight remotely operated vehicle dives we had in the Corner Rise Seamount Chain, we discovered areas of high biodiversity and high densities of ecosystem engineering species, including sponge and coral garden areas on MacGregor and Caloosahatchee Seamounts, respectively. We also observed human impacts from dredge or trawls on Yakutat Seamount and observed an overall high diversity of fish species across the Corner Rise Seamounts.

Published July 16, 2021