by Peter Etnoyer, Ph.D., Marine Biologist, NOAA National Centers for Coastal Ocean Science

Figure 1: Orange fly-trap anemone on Lophelia pertusa coral reef at Viosca Knoll near 500 meters (1,640 feet) depth. Image courtesy of Lophelia II: Reefs, Rigs, and Wrecks 2009 Expedition, NOAA OER/BOEM. Download larger version (jpg, 932 KB).

Throughout this expedition, you can expect to see many colorful and interesting living animals on the seafloor. They represent the benthos. Benthos refers to all the organisms which live on, in, or near the sea bottom (Figure 1).

Among the most fascinating and important within this group are the deep-sea corals in the Phylum Cnidaria. Corals, sea anemones, sea fans and sea whips are all cnidarians in the Class Anthozoa, which means ‘flower-animal’ in Greek. Corals are closely related to sea anemones and jellyfish in that they have stinging cells, but they are distinguished by the skeleton structures they secrete on the seafloor, which provide habitat for numerous other species.

Deep-sea corals have much in common with shallow tropical corals, but they are much less understood and relatively poorly mapped and explored. Shallow reef-building corals occur in the tropics around the world and are recognized as havens for biological diversity. Of the 34 recognized animal Phyla, 32 (about 94 percent) are found on tropical coral reefs, compared to the nine Phyla (~ 26 percent) found in terrestrial tropical rainforests.

Deep water corals (>50 meters; 164 feet) are difficult to access using conventional SCUBA gear. Instead, researchers need sophisticated tools like submersibles and robots to study deep corals in their natural environment. As technology improves, scientists are beginning to understand these ecosystems.

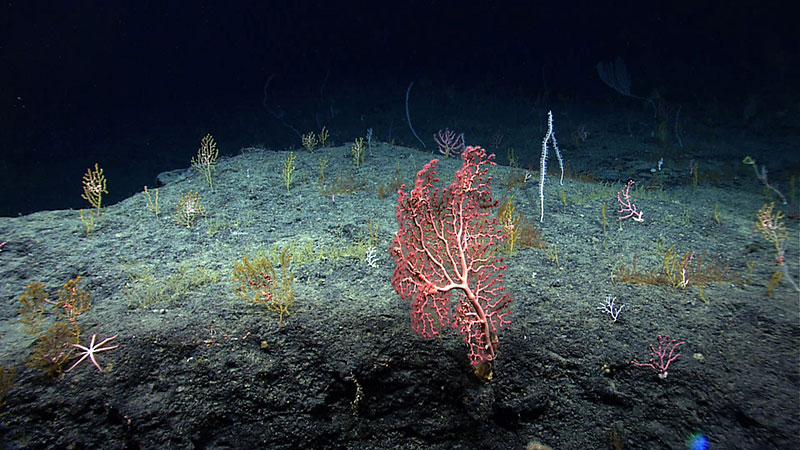

Figure 2: A field of sea fans (Callogorgia sp.) with brittle stars (Asteroschema sp.). Image courtesy of Lophelia II: Reefs, Rigs, and Wrecks 2009 Expedition, NOAA OER/BOEM. Download larger version (jpg, 1.3 MB).

Did you know that there are more species of corals in deep water (>50 meters) than there are in shallow waters (<50 meters)? In the Gulf of Mexico, there are more than 250 species of deep-sea corals (species occurring deeper than 50 meters), compared to the 100 or so species in shallow waters. These deep-sea species include stony branching corals, cup corals, octocorals, and black corals; similar to the types and orders seen on some shallow reefs. Many of these species are host to shrimp, crabs, fish, sea stars, barnacles and brittle stars (Figure 2). Deep-sea coral diversity begets more diversity. Deep-sea coral structures provide shelter or feeding opportunities for numerous species.

NOAA’s Office of Ocean Exploration and Research and its partners have been documenting deep-sea corals since 2001, in explorations around the Atlantic and Pacific. Some generalities about deep-sea corals are beginning to emerge, namely that corals occur in all regions of the U.S., they grow very slowly, co-occur with other species, and are slow to recover from disturbance. The Gulf of Mexico is actually one of the more intensely developed and most explored ocean basins in the U.S., partly because of the oil and gas industry. Yet, there are still many areas that scientists have yet to explore. Many new discoveries await.

Figure 3: Madrepora oculata colony and with several deep-sea red crab Chaceon quinquedens. The ‘X’ marker was placed by deep-sea researchers in 2010 so they could return to this spot. Image courtesy of Lophelia II: Reefs, Rigs, and Wrecks 2009 Expedition, NOAA OER/BOEM. Download larger version (jpg, 8.2 MB).

Figure 4: A rare instance of deep-sea predation captured on camera, a sea urchin munches on a Plumarella octocoral. This may be the first time sea urchin predation on coral was captured so close-up, thanks to the incredible image capabilities of the Deep Discoverer ROV. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, Gulf of Mexico 2014. Download larger version (jpg, 1.5 MB).

In the last 10 years, at least 10 new species of deep-sea corals have been described from the Gulf of Mexico. New relationships have been discovered as well. We have observed a strong affinity of deep-sea red crabs Chaceon quinquedens with colonies of the deep-sea coral Madrepora oculata. See the mosaic image in Figure 3. How many crabs can you count in that one colony? We have also observed that sea urchins eat Plumarella corals. No one knew this until the moment was captured aboard during the Okeanos Explorer Gulf of Mexico 2014 expedition (Figure 4).

One pattern that has emerged through the years is that deepwater species are stratified by depth, meaning certain coral species can be expected to occur in certain depth zones. Depth is among the best predictors of coral occurrence. For example, the stony branching coral Lophelia pertusa, the octocoral Callogorgia sp., and the black coral Leiopathes glaberrima may be expected to occur between 300-800 meters (984 - 2,624 feet), when seafloor conditions are right. In deeper and colder waters near 1,800 meters (5,905 feet) depth, one is more likely to encounter corals in the genera Paramuricea, Iridogorgia, Chrysogorgia, and Metallogorgia.

Explorers have also learned to expect the unexpected. One good example is the discovery of bubblegum corals (Family Paragorgiidae) in the Gulf of Mexico. Bubblegum corals are common in many parts of the world, but had not been documented in the Gulf until recently. The first observation on record was in 2008, using a small remotely operated vehicle (ROV) aboard the Lophelia II: Reefs, Rigs, and Wrecks expeditions. Researchers found and collected a white Paragorgia colony with red polyps near 350 meters (1,148 feet) depth in the Green Canyon areas. In 2009, using the Jason II ROV, the Lophelia II team found and photographed a large Sibogagorgia colony at 1,500 meters (4,921 feet) depth in DeSoto Canyon. Then, after the Deepwater Horizon oil spill in 2012, scientists using NOAA Ship Okeanos Explorer and the Deep Discoverer ROV documented perhaps the largest bubblegum coral colony of Paragorgia regalis ever observed in the Gulf, over one meter (three feet) tall, in surveys adjacent to the well head. Remarkably, the colony appeared to be uninjured.

Figure 5: The deepwater environment of the Florida Escarpment proved to be a good habitat for diverse deepwater coral communities. In this image alone, there are four different species of corals, including bubblegum and bamboo corals. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, Gulf of Mexico 2014. Download larger version (jpg, 1.4 MB).

This discovery helps to illustrate the point that deep-sea ecosystems have not been explored yet, even where human activities are high, and these activities impact ecosystems that we don’t fully understand. More observations of bubblegum corals were to follow. In 2014, Deep Discoverer ROV explored the dramatic edges of the West Florida Escarpment near 1,800 meters (5,905 feet) depth and Paragorgia sp. was encountered once again (Figure 5). At one point, the Deep Discoverer ROV encountered a very dense aggregation of small colonies, suggesting a recent recruitment event.

In these last 10 years, we have gone from one observation of one bubblegum species to numerous observations of several species. Now we know what to look for.

November 2017 marks the beginning of a new season of fieldwork and exploration in the deep Gulf of Mexico with NOAA Ship Okeanos Explorer. New observations will add to the ever-growing body of knowledge about our unknown oceans. It’s also possible that Deep Discoverer ROV will collect some new species of deep-sea coral on this expedition or perhaps obtain some new unprecedented material of an old species, for genomics and DNA. There is so much to learn. It’s exciting to discover new life on Earth, right here on the American frontier.

Learn more:

The Measure of a Coral

Cold-water Corals in the Gulf of Mexico