By Jay Lunden, Principal Investigator - Temple University

and Sam Georgian, PhD student, Temple University

A close-up image of a single Eumunida picta squat lobster perched on a live Lophelia pertusa thicket. Image courtesy of Lophelia II 2012 Expedition, NOAA-OER/BOEM. Download larger version (jpg, 639 KB).

When most people think about corals, they usually imagine a sunny tropical reef speckled with fishes, crabs, snails, and other creatures on a colorful rocky outcrop. However, not all corals are found on island coasts in shallow seas. In fact, over half of all known coral species are found in deep, dark waters where temperatures range from 4-12° C. For this reason, we call these corals the “cold-water corals,” and they are found all over the world – including the Gulf of Mexico.

Corals come in many shapes, sizes, and colors. Biologists use these morphological characteristics and genetic information to group corals into different taxonomic categories. All corals have certain things in common, such as a soft body (called a polyp) with two true tissue layers and the ability to (generally) make some form of skeletal material. Since corals are cnidarians, they also have stinging cells called cnidocytes equipped with nematocysts that help them to defend themselves and to capture prey. Some corals are colonial, and the polyps are connected to each other by tissue called coenosarc. In the deep waters (> 450 meters) of the Gulf of Mexico, several taxonomic groups are represented by numerous species of cold-water corals.

One of the most widely recognized groups of corals is the hard corals – the Scleractinians. Scleractinian corals build a hard skeleton made out of calcium carbonate and can form massive reefs that host diverse assemblages of fishes and invertebrates. These corals are also noted for having tentacles in multiples of six.

Two species of scleractinian corals typically found in the Gulf of Mexico are Lophelia pertusa and Madrepora oculata. Lophelia is the more common of the two in the Gulf, and is generally found between 300-600 meters water depth. One of our primary objectives on this cruise is to look for these species of corals growing on oil and gas platforms. We will use images to calculate the growth rates of these corals.

An outcrop containing a large white Leiopathes colony and several small fragments of Lophelia pertusa. Image courtesy of Lophelia II 2012 Expedition, NOAA-OER/BOEM. Download larger version (jpg, 440KB).

The black corals, or Antipatharians, are also common at several locations in the Gulf. These corals have polyps surrounding a black axis made out of chitin and proteins. These corals are flexible and can bend if a strong current passes over them. Antipatharians are very long-lived, and some species have been aged to over 2,000 years.

One species that we frequently encounter in the Gulf is Leiopathes glabberima. Leiopathes colonies can sometimes be as tall as three meters high, and consequently can serve as habitat for some species of fishes and invertebrates. In fact, some species of sharks and skates will use the colonies as anchors for egg pouches.

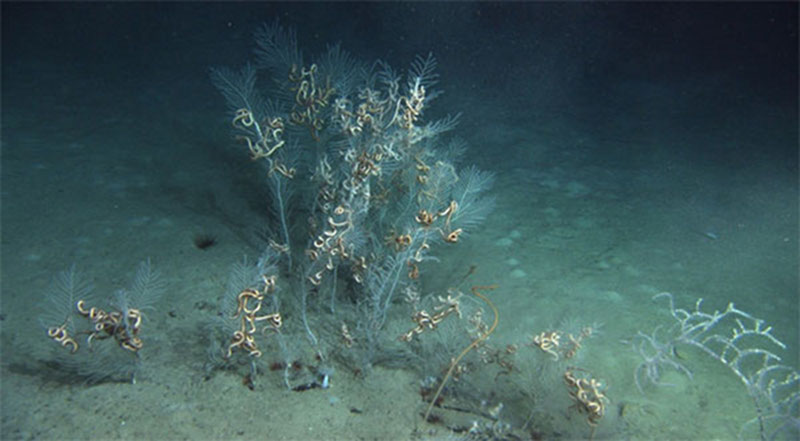

A large number of ophiuroid associates colonize a patch of large Callogorgia colonies. Image courtesy of Lophelia II 2012 Expedition, NOAA-OER/BOEM. Download larger version (jpg, 793 KB).

Perhaps the most complex group of corals in the deep Gulf is the Octocorals, which includes sea fans, sea pens, and sea whips. The octocorals are incredibly diverse, with at least 162 species in the Gulf of Mexico alone.

Octocorals are unique in that they produce sclerites – tiny structures made of calcium carbonate embedded within the animal’s tissue. These sclerites have various morphologies and provide protection and give shape to the coral. Biologists use the sclerites to classify the many species of octocorals.

One species of octocoral that our project focuses on is Callogorgia americana. We have spent a significant amount of time and effort collecting this species at various sites to determine gene flow and connectivity in the Gulf. Using this information, we can designate certain areas of the Gulf as “source” populations that will become a high priority for conservation and protection.