By Peter Etnoyer, NOAA National Centers for Coastal Ocean Science

March 28, 2012

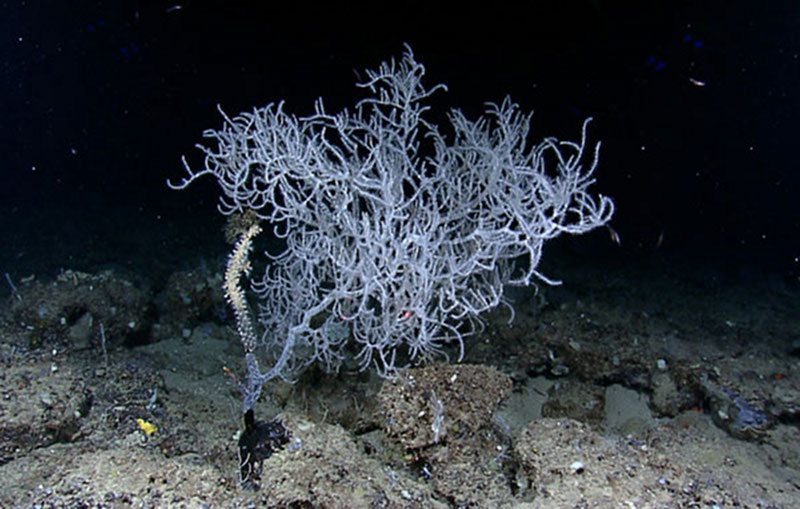

Figure 1: A Lophelia pertusa colony at 390 meters depth in the DeSoto Canyon region. Lasers are visible at the bottom center of the screen, 10 centimeters apart. They indicate that this colony is 60 centimeters across. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, Gulf of Mexico Expedition 2012. Download larger version (jpg, 428 KB).

This has been quite an interesting expedition so far, not only because of what we're exploring here in the deep Gulf of Mexico, but also because of the way we're exploring it. Along with many others, scientists from NOAA's National Centers for Coastal Ocean Science/Center for Coastal Environmental Health and Biomolecular Research (NCCOS/CCEHBR) in Charleston, SC, are participating remotely in the expedition using ‘telepresence’ technology via internet. We're far from the ship, but chat rooms, conference lines, video streams, FTP sites, and emails keep us plugged into the action aboard the NOAA Ship Okeanos Explorer.

Figure 2: A frame-grab from high-definition video camera on the Little Hercules ROV showing live branches of Lophelia pertusa (in white) growing over dead branches (in brown). Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, Gulf of Mexico Expedition 2012. Download larger version (jpg, 1.3 MB).

Our role in this mission is to document deep-sea coral abundance, diversity, health, and condition. NOAA has a mandate to explore and identify deep-sea coral aggregations under Magnuson-Stevens Sustainable Fisheries Conservation Act (2009), but given the Deepwater Horizon event in April 2010, we’re also searching for effects from the oil spill.

The Deep-Sea Coral Ecology program at the NCCOS/CCEHBR lab works collaboratively with other NOAA offices, like the Deep-Sea Coral Research and Technology Program, Office of National Marine Sanctuaries, and Office of Ocean Exploration and Research to achieve our shared goals to identify and protect healthy deep-sea coral ecosystems.

The remotely operated vehicle (ROV) Little Hercules is an especially useful tool for this work because it can access extreme depths that few submersibles can reach. The ROV is equipped with a high-definition camera and excellent lighting that allow us to see in great detail. For the first time, we can observe many of the coral species in their natural habitat. The ship and ROV have excellent navigation systems, too, so we can 'mark' the position of coral colonies with great accuracy by dropping 'virtual targets' to return another day.

Figure 3: A Leiopathes black coral colony at 425 meters depth on the West Florida escarpment. Red lasers are visible on the branches and polyps near the middle of the screen, 10 centimeters apart. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, Gulf of Mexico Expedition 2012. Download larger version (jpg, 924 KB).

An important aspect of this work is the pair of red lasers you may see in the images we’re collecting. You can learn a lot from a pair of lasers. These lasers are set 10 centimeters (4 inches) apart. They allow us to measure the size of a coral colony, the area of the seafloor, and the distance between a coral and its nearest neighbor, among other things.

Using this scale we can estimate live coral cover and colony size to infer coral health, colony age, and even reproductive output. For example, Lophelia pertusa is a reef-building coral that grows about 300-800 meters deep in Gulf of Mexico. Healthy Lophelia aggregations are large reefs with a high percentage of live coral. At the Dragon Head site in DeSoto Canyon, we observed some healthy colonies 60 centimeters in diameter (Figures 1 and 2), but the majority of seafloor area on the dome feature was dead coral. So, overall health was relatively poor compared to some other sites in the Gulf of Mexico.

Black coral colonies grow very slowly. We know this because black corals (and sea fans) have annual growth rings like the trees on land. The radial growth rate – increase in circumference- of Leiopathes black coral colonies in the Gulf of Mexico falls between 8-22 microns per year (Prouty et. al, 2011). One Leiopathes coral we observed on West Florida Escarpment at 425 meters depth was 1.7 centimeters in diameter at the base (Figure 3). Based upon known growth rates, we estimate the age of this colony to be 400-1000 years old. It’s like finding old-growth forest deep undersea.

So, now you know what we're doing next time you see little red dots bouncing around on a coral or tubeworm. We’re ‘sizing them up’, as they say in mission control aboard Okeanos Explorer.

Prouty NG, Roark EB, Buster NA, Ross SW (2011) Growth rate and age distribution of deep-sea black corals in the Gulf of Mexico. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 423:101-115. http://www.int-res.com/abstracts/meps/v423/p101-115