By Diva Amon - University of Hawaii at Manoa

June 22, 2016

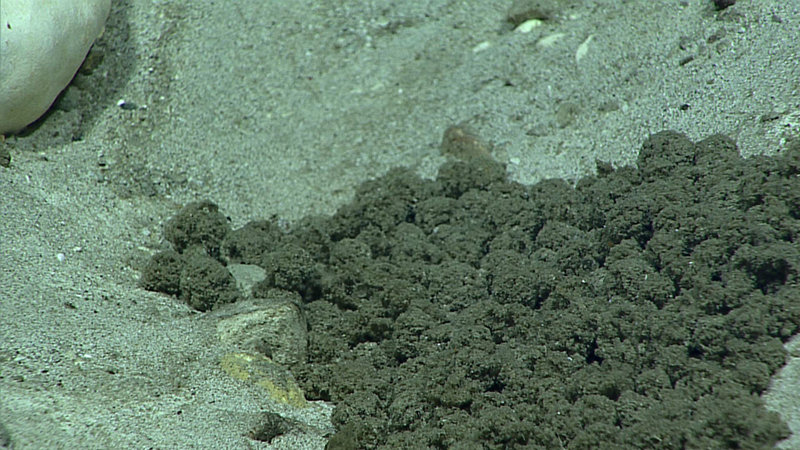

The strange spheres on Hadal Ridge. Image courtesy of NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, 2016 Deepwater Exploration of the Marianas. Download larger version (jpg, 1.0 MB).

As deep-sea biologists, we are constantly surprised by new animals and fascinating discoveries. Having been a science lead onboard NOAA Ship Okeanos Explorer for Leg 1 of the current expedition, I know firsthand that the Mariana region is no exception!

Despite seeing so many new species and records, we usually end up with a pretty good guess of what it is we are looking at through the power of telepresence. A great Internet connection means that we are joined daily by dozens of scientists who are watching the video with us in real time and can share their thoughts with only a few seconds delay. This means that an answer to most questions can usually be found at the end of our headsets. And if not, there’s always Google!

On land, we live in an age of instant information – although that is limited on most research vessels, we are lucky to have almost unlimited connectivity on the Okeanos Explorer.

Occasionally, however, the deep sea still has mysteries to throw at us. On these occasions, the whole science party is dead silent because no one has any idea what we’re looking at! Yep, it happens, and there have been several of these moments during this expedition.

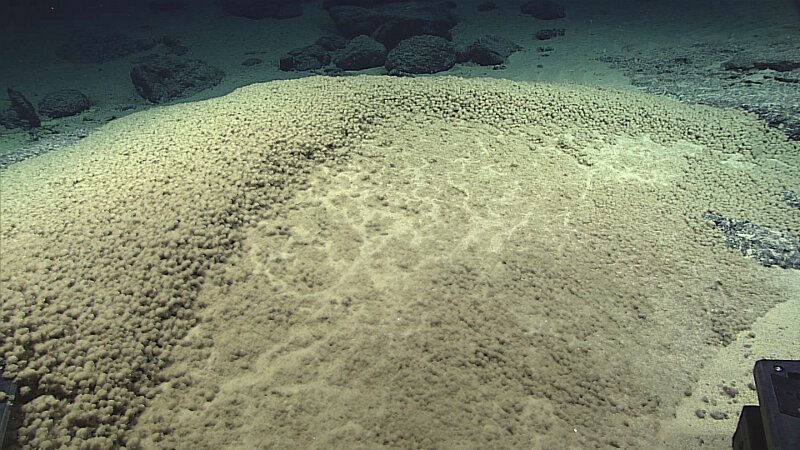

A field of the small, sedimented balls that stumped scientists during the Leg 1 dive on Enigma Seamount. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research. Download larger version (jpg, 1.5 MB).

During the fourth dive of both Legs 1 and 3 (Enigma Seamount and Hadal Ridge, respectively), we came across strange little spheres that covered the seafloor. They were one to two centimeters in diameter, had a mesh-like structure beneath their fluffy coatings, and were so abundant in some places that they formed large mounds.

On Leg 1, initial guesses from the scientists included fecal pellets, sponges, foraminifera, colonial radiolarians, or feeding balls from crustaceans. The strange mesh-like (or reticulated) structure suggests that they are not balls of detritus, ruling out feeding balls and fecal pellets. However, because they collect in drifts, they are light enough to be moved around by the currents.

We used the remotely operated vehicle manipulator claw to determine how soft or hard the balls were. Although they were more robust than we were expecting, they still crushed quite easily into dust.

University of Texas, Dallas scientists Dr. Ignacio Pujana and Dr. Bob Stern have worked extensively in the Mariana region and previously speculated that they were gromiids (a distinct taxon related to the foraminifera).

However, foraminifera expert Professor Andy Gooday from the National Oceanography Centre in Southampton, UK, thinks otherwise. He says that although the size and shape are right for gromiids, they lack the typical smooth, shiny reflective surfaces. He thinks it’s possible that these spheres are instead xenophyophores (giant single-cell foraminifera), as the size matches and the system of polygonal cells is reminiscent of some xenophyophore tests. However, although xenophyophores are common on seamounts, he worried that they are too light and abundant. The fluffy matrix in which the mesh-like structures seem to be embedded doesn't resemble anything he has ever seen before.

Komoki, another type of foraminifera, also form reticulated balls, but are not usually this big and don’t look like this. Other suggestions are that these balls are something pelagic that bloomed and then settled on the seafloor, or even dead sponges! But who knows?! Nearly two months from when these balls were first spotted during Leg 1 of this expedition, we are no closer to knowing what they actually are.

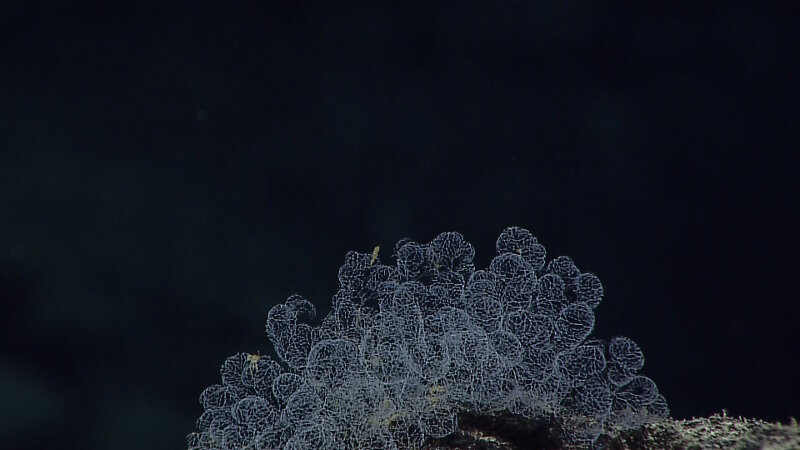

Strange feathery, wispy things. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research. Download larger version (jpg, 863 KB).

Another weird thing we saw occurred on Leg 1 during Dive 6 at Fina Nagu Caldera C. At 2,750 meters, we came across some spherical white things attached to rocks. On further investigation, they actually seemed more feathery, with branch-like structures that curled onto themselves so they appeared round.

There was speculation that these are colonies of hydroids or bryozoans, but that isn’t saying much, as those are two totally different phyla (Cnidaria or Bryozoa)! To put that into context, it’s as bad as confusing a monkey (Chordata) with a cockroach (Arthropoda)!

And the confusion continues, even though we are only a few dives into Leg 3! The biological community at Farallon de Medinilla 2 (Dive 1) was dominated by a diverse community of large coral colonies. Most of these were easy to identify to family (our scientists ashore are awesome at coral identification). However, many of the corals had lots of strange green stringy things attached, waving wildly in the strong currents.

Guesses as to what the stringy things are included sponges, hydroids, or bryozoans that could have been growing on the corals. Perhaps it’s actually spiralised zucchini or spinach spaghetti?! The most plausible guess (and perhaps why we were all stumped!) is that it is chlorophyta or green algae that drifted down from shallower depths and got caught in the current on the corals. Green algae does not occur in the deep sea (>400 meters depth) because of the lack of sunlight that it needs for photosynthesis (just like terrestrial plants), so perhaps that’s why most of us deep-sea biologists were stumped!

Spinach spaghetti? Spiralized zucchini? Maybe green algae from up slope, here, attached to coral. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research. Download larger version (jpg, 790 KB).

The stringy green things clinging to a barnacle. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research. Download larger version (jpg, 1.0 MB).

Although these examples show that even the experts don’t always have the answers, there are some positives. Getting stumped helps all of us to understand why deep-sea science is important, justifies our continued interest in deep-sea exploration, and also highlights how exciting both exploration and research can be. New species also have the potential to result in discoveries with societal benefits in the form of new knowledge or products.

More importantly though, it reminds us to remain humble, as there is still much to learn and appreciate about our deep ocean and the incredible planet we live on.