By Frank Cantelas - NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research

July 9, 2016

The B-29 Superfortress, designed by Boeing, fulfilled the need for a bomber capable of flying over 5,000 miles while carrying a large payload. It represented very advanced technology for the time with a pressurized cabin and a remote, computer controlled fire control system to direct four machine-gun turrets to protect against enemy aircraft attacks. The plane was used from June 1944 through the end of the war and included missions to drop supplies to prisoners of war in Japan. Image courtesy of the United States Air Force. Download larger version (jpg, 705 KB).

On July 9, 2016, we had the opportunity to investigate two sonar anomalies that we thought might be a B-29 aircraft lost in World War II near Tinian Island.

Tinian, captured in 1944 as part of the U.S. “island hopping” strategy, became one of the largest airbases during the conflict and a center for B-29 operations. The introduction of the B-29 in 1944, featuring many advanced technologies, gave America the capability to carry out long-range bombing missions against Japan, often traveling more than 3,000 miles round trip. Many of these planes departed from Tinian’s North Field which is only about five miles from the Island of Saipan, just across the Saipan Channel. Between late-1944 and the end of 1945, several B-29s flying from North Field suffered mechanical difficulties or other problems and crashed in the channel or off the opposite side of the island.

In April 2016, during Leg 1 of this expedition, NOAA Ship Okeanos Explorer mapped around the north end of Tinian, using the ship’s multibeam sonar. The seafloor on the west side of the island proved too rugged to find potential targets among rock outcrops and coral. Our efforts became focused on the channel between the islands where the deepest part is covered by sand.

There were numerous discussions about which of several targets we should examine. Crash reports were pretty clear about how most of the planes that ditched or crashed off Tinian broke apart or even exploded. Additionally, wreckage that has been on the bottom for 70 years does not necessarily look like pieces of an airplane on a sonar image.

One target, out of several in the area, stood out because it had a harder surface than the surrounding sand. Not knowing for sure if this was airplane wreckage or a rock, we decided to take a look.

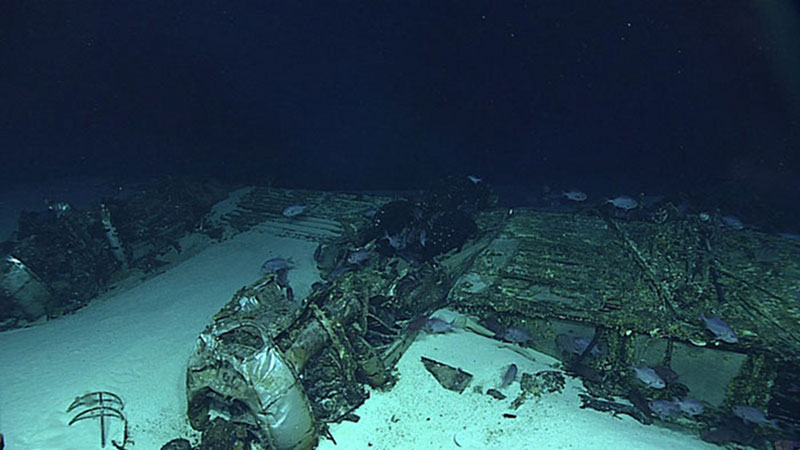

This site is one of many aircraft lost in the vicinity of Tinian and Saipan. The B-29 Superfortress, one of the largest aircraft flown by the United States in World War II, had a wingspan measuring just over 141 feet. The wing came to rest on the sea floor upside down with the landing gear and three of the radial engines still attached. Image courtesy of NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, 2016 Deepwater Exploration of the Marianas. Download larger version (jpg, 761 KB).

After the remotely operated vehicle (ROV) Deep Discoverer (D2) reached the seafloor near the sonar target we dubbed ROMEO, a ghostly reminder of World War II quickly came into view: the wing and engines of a B-29 Superfortress.

While looking at this site, I knew many young men had perished in these crashes, paying the ultimate price for their country. After 70 years, many families are still asking about what happened to their husbands, fathers, brothers, uncles, or cousins. It’s very likely that this is one of those crash sites, and we treated it respectfully, never touching or disturbing the site, while looking for answers about its identity and condition.

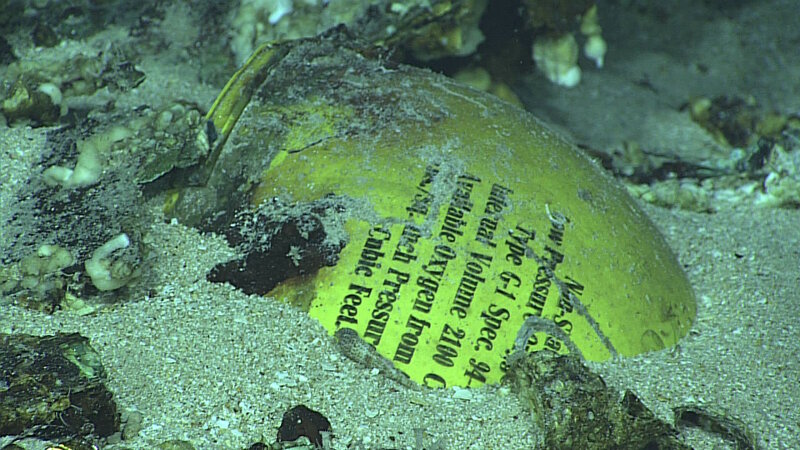

This yellow tank is an oxygen cylinder used in the system to pressurize the crew’s cabin spaces. It is in remarkably good condition with the writing still legible. Image courtesy of NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, 2016 Deepwater Exploration of the Marianas. Download larger version (jpg, 1.0 MB).

As we investigated the wing, we found that three of the four engines are still attached and the rubber tires of the landing gear are retracted into the upside down wing. On closer inspection, it appears that one or more of the engines may have caught fire. Engine fires were not uncommon in B-29s and this clue could, after reviewing crash reports for aircraft lost in the channel, help identify the plane. A bright yellow object in the wreckage behind the wing turned out to be an oxygen cylinder used in the system that pressurized the crew compartments.

After spending time carefully documenting the wing, the ROV moved toward the second target found during our earlier sonar survey we designated as JULIET. In the scanning sonar, we saw an object beyond our visual range rising off the seafloor several feet. An unknown object with vertical relief is a potential snag hazard for the ROV, so we approached cautiously.

The forward gun turret, located some distance from the wing, is evidence that the aircraft broke apart. A panel of dials found in the wreckage is part of the flight engineer’s station, indicating this section of wreckage is a part of the B-29s forward section. Image courtesy of NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, 2016 Deepwater Exploration of the Marianas. Download larger version (jpg, 992 KB).

A short vertical tube appeared out of the darkness surrounded by other debris. This is a disarticulated part of the forward section of the plane behind the cockpit. The cylindrical tube is the forward gun turret with the gun barrels buried in the bottom. Nearby is a board containing dials from the flight engineer’s control panel and next to it is an escape hatch that would have been next to the flight engineer’s station.

As we moved beyond this point, we found scattered debris and finally the horizontal stabilizer of the tail. Shortly after this discovery, the dive terminated as weather and current conditions had worsened to the point where it was no longer safe to continue the dive.

Despite finding major portions of the aircraft, large sections of the fuselage were not found, nor the tail, a very prominent feature which had an identifying insignia, although it is questionable whether the insignia would have survived. There are many possible explanations. The aircraft could have broken up on the surface and currents would have caused the sections to drift apart while sinking through the water column. It’s also very likely that portions of the plane are buried by sand moving along the floor of the channel, as currents in the area are very high.

Our exploration dive demonstrated that the B-29s lost in the channel still exist and, after 70 years, are in fairly good shape. Others bombers will likely be found by future research expeditions and perhaps one of them will revisit this site.

At this point, the identity of the plane remains unknown.

Tinian and Saipan served as major air bases during the final year of WWII with B-29 bombers flying long-range missions to Japan. Many aircraft were lost on take-off and landing. The lost aircraft have great significance to American history yet none of the B-29s that crashed in the Saipan Channel have ever been discovered. During the final dive for Leg 3 of the expedition, we explored sites that had been identified with exploration targets to search for B-29 aircraft during previous mapping. The dive provided the first information on B-29 bomber wreckage resting in the deep water of the channel and provided initial information on the state of preservation of the aircraft and the environmental conditions affecting the sites. Video courtesy of NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, 2016 Deepwater Exploration of the Marianas. Download (mp4, 134.0 MB).