By Alan P. Leonardi, Ph.D. - NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research

May 13, 2015

NOAA Ship Okeanos Explorer passes Castillo San Felipe del Morro as she departs San Juan Harbor. Image courtesy of NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research. Download larger version (jpg, 187 KB).

For those who don’t know me or haven’t met me yet, I am the Director of NOAA’s Office of Ocean Exploration and Research (OER). Prior to joining OER in October 2014, I was the Deputy Director of NOAA’s Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory in Miami, Florida. My science background is quite varied with degrees in both meteorology (B.S.) and physical oceanography (M.S. and Ph.D.), with a primary focus on air-sea interaction, coupled ocean-atmosphere modeling, and understanding large-scale ocean dynamics.

So, how does a classically trained meteorologist and physical oceanographer become the Director of Ocean Exploration and Research for a government agency, you ask? Well, it is a circuitous story with a lot of twists and turns and plot changes along the way. I will spare you the fine details for another time, but it all started with an opportunity with NOAA’s National Ocean Service back in 2003. Along the way, I gained experience coordinating and leading NOAA’s broad suite of ocean, atmosphere, ecosystem, and climate modeling activities; working in policy development and strategic direction setting for NOAA Research, the primary research arm of NOAA; and even spent some time working at Google helping integrate NOAA observational data and products into the popular “Google Ocean” product.

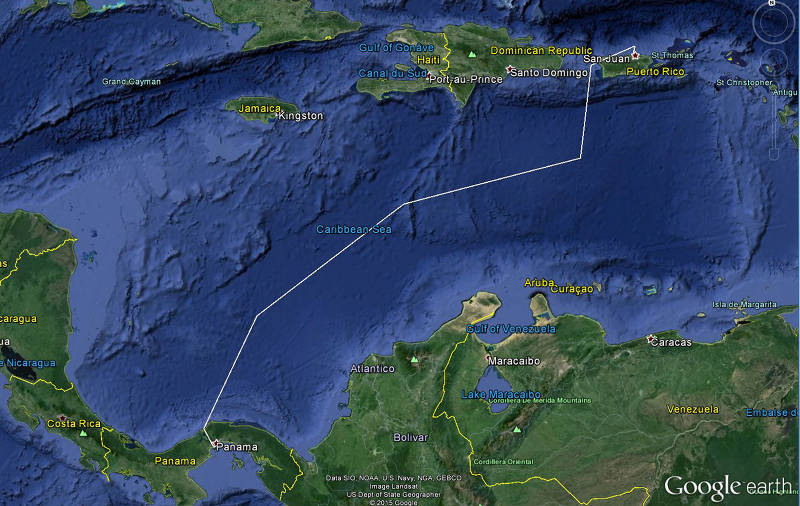

At the conclusion of Océano Profundo, Tropical Exploration 2015 sailed from San Juan, Puerto Rico, to Panama City, Panama. Image courtesy of NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, Tropical Exploration 2015. Download larger version (jpg, 297 KB).

Through it all, I always felt like the research NOAA was performing was truly innovative and leading the way for much of the research community. So, when the opportunity arose to become part of OER, I jumped at the chance. After all, how can one not get excited about working on the cutting edge of ocean technology while simultaneously exploring and mapping the world’s deepest and unknown places, uncovering the hidden mysteries of the deep ocean flora and fauna, observing historically important shipwrecks, and sharing all of that information – and joy – with a wide variety of audiences worldwide? For me, it is an honor to be here and I feel like it is both an exciting and meaningful time to be a part of the ocean exploration community.

Straight off the heels of the successful Océano Profundo 2015 expedition, NOAA Ship Okeanos Explorer, its crew, OER staff, and partners began the long trek west across the Caribbean Sea, through the Panama Canal, and eventually on to Honolulu, Hawaii, in advance of our next expedition series – the Campaign to Address Pacific Monument Science, Technology, and Ocean NEeds, or CAPSTONE.

The Océano Profundo 2015 expedition was a great success – we learned a lot in our time exploring Puerto Rican waters. We conducted a series of cruises focused on the diversity and distribution of deepwater habitats in Caribbean trenches and seamounts, we dedicated time to exploring the Puerto Rico Trench, we tested the Deep Discoverer remotely operated vehicle (ROV) down to 6,000 meters, and we saw a whole host of interesting organisms. Details of many of these activities can be found in the mission logs. One of my favorites was the sea toad seen in the Mona Passage.

As ROV Deep Discoverer approached, this sea toad (Chaunax sp.) “walked” away. Image courtesy of NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, Tropical Exploration 2015. Download image (jpg, 82 KB).

Following the successful Océano Profundo 2015 expedition and a brief in-port period to allow for crew rest and to handle some needed maintenance, Okeanos Explorer departed San Juan, Puerto Rico, the morning of May 8.

Before we could get fully underway, we had a local expert join us onboard to “swing the compass” – a process where the ship’s compass is adjusted and to remove any deviations that may have been introduced, usually as a result of proximity to metal objects, magnetic fields, or electrical equipment.

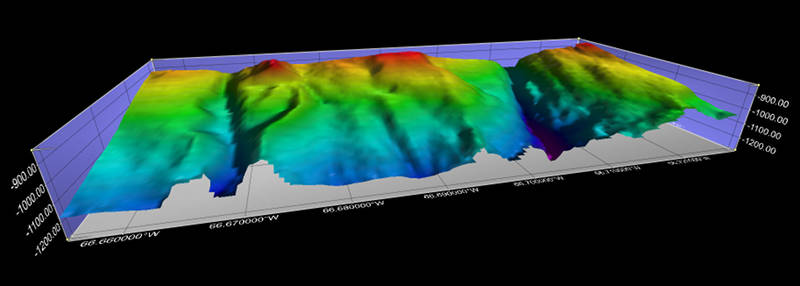

Once fully underway, the mapping team initiated data collection for this short transit leg between Puerto Rico and Panama. Even though this leg was primarily for transiting the ship from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean, there was plenty of valuable mapping that could take place while underway. Given we are a U.S. vessel, we had the ability to map in U.S. waters and international waters without much trouble. Mapping in the exclusive waters of another country, on the other hand, typically requires permits. As a result, we were really only looking at about 48 hours of mapping before we would need to turn the equipment off. Despite the brief mapping period, we were still able to get some very interesting data from little known areas of the Caribbean Sea.

During the first day of the expedition, we mapped these canyon features along the Arecibo Amphitheater. Figure created in Fledermaus. Image courtesy of NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, Tropical Exploration 2015. Download larger version (jpg, 126 KB).

With all of the wonderful things we see with the Okeanos Explorer in the deepest part of the ocean, we often lose sight of the amazing things we can see on the coast or on land as well. During this transit, I was fortunate to see one of those: the Panama Canal, one of the Seven Wonders of the modern world! For all you engineering enthusiasts out there, I only have one thing to say: wow!

To say this was a monumental undertaking and has reaped immense benefit for the entire world is no understatement. Indeed, since opening in 1914, over one million ships have passed through its hallowed locks, carrying an estimated one trillion tons of cargo. Moreover, from the time the canal was conceived to the point at which it was completed, 45 years had past, about $375 million (in 1914 dollars) had been spent on materials, over four million cubic yards of concrete poured, 11 different presidents took up residence in the White House, and tens of thousands of workers contributed to some aspect of its construction – many of whom lost their lives in the process.

One of the most novel aspects of the canal engineering was the use of locks. As vessels enter the canal they are faced with a series of locks – a system of gates designed to raise and lower ships within a river or canal. Each of these locks uses pairs of panel doors, six pairs of panels in all each measuring between 47 and 82 feet tall and weighing between 350 to 660 tons, to allow water levels within the lock to rise by roughly 35-40 feet, thereby bringing vessels up to the water level in the next lock. Once the vessel is at the new water level, one lock end opens and the vessel is allowed to enter the next lock, or if in the last lock, to enter in the inland passageway that travels through Lago (Lake) Gatún, the Rio (River) Chagres, and Lago Miraflores. At the other end of the route, locks are used in a similar manner to lower the vessels to meet the water levels of the surrounding ocean.

Okeanos Explorer enters the Panama Canal. Image courtesy of NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, Tropical Exploration 2015. Download image (jpg, 57 KB).

We were lucky enough to enter the first lock in the late afternoon during daylight, so we got a very good look at how the entire process works. By the time we made it through the third lock about 1.5 hours later, it was already dark. The transit between the entrance locks to the exit locks is about three hours, meaning that the entire process takes about 6 hours from end to end, not including waiting time to enter the locks which can often add several additional hours. For us, it meant entering just before dusk and exiting a few hours before dawn. Considering it takes only 8-10 hours (without waiting) to make it through the 48-mile long canal versus 29 days and nearly 8,000 miles around the tip of South America, I think the transit time was well worth it! Either way, it was a great experience and another item I can take off of my bucket list.

Once we reached Panama City, Panama, I unfortunately had to leave the ship and fantastic crew behind and head back to the U.S.; my sailing ended here for the time being. While I am excited to get back to the office and to see my family and friends, I also know I will miss the lure of the sea while working in an office again. It is nice to see the magic of our science and technology working hand in hand to bring you data, images, and video of places never before and not easily seen. Hopefully, this won’t be my last opportunity to sail with the Okeanos, the crew, and the OER team. Next up for OER and Okeanos Explorer: the Pacific Ocean CAPSTONE effort.

The locks of the Panama Canal closing behind Okeanos Explorer. Image courtesy of NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, Tropical Exploration 2015. Download image (jpg, 46 KB).

CAPSTONE is a multi-year series of expeditions aimed at collecting baseline information supporting NOAA’s science and management requirements associated with U.S. marine national monuments and other protected places in the Pacific Ocean. These expeditions will also highlight the uniqueness and importance of these symbols of ocean conservation. During this next period, OER and the Okeanos Explorer will work in and around the main Hawaiian Islands, Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument, the Hawaiian Islands Humpback Whale National Marine Sanctuary, and Johnston Atoll (part of the recently expanded Pacific Remote Islands Marine National Monument, now known as Pacific Islands Heritage Marine National Monument) and will complement previous field work conducted by the NOAA, government and university partners, the Schmidt Ocean Institute, and others.

Perhaps I will get another chance in the next few years to join the team in the Pacific Ocean for some of the exciting CAPSTONE expeditions. In the meantime, I will have to settle for living vicariously through the onboard explorers and reading, listening, and watching live as they explore the mysteries of the Pacific Ocean. Hopefully, you will join them as well. Until next time, onwards and downwards!