By Adela Roa-Varón - Department of Fisheries Science, Virginia Institute of Marine Sciences

April 25, 2015

[ En español ]

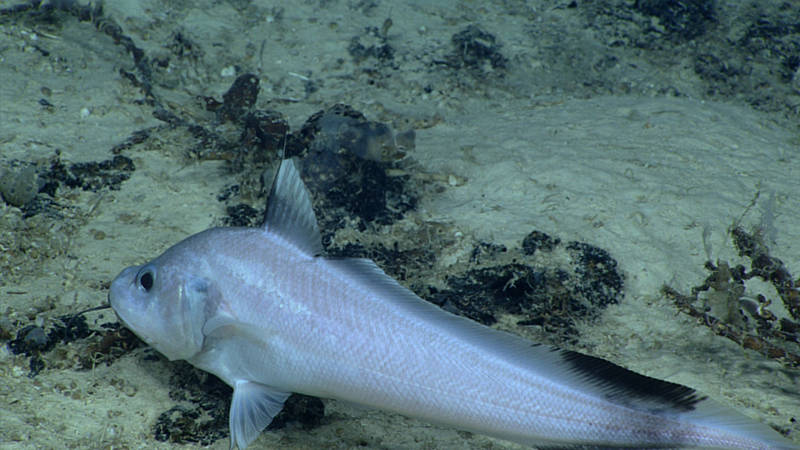

One of the deepest occurring grenadiers, Coryphaenoides armatus (Family Macrouridae), imaged during our first dive on the Arecibo Ampitheater, north of Puerto Rico. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research. Download larger version (jpg, 1.4 MB).

Fishes of the order Gadiformes (e.g., cods, hakes, rattails and their allies) inhabit cool waters in every ocean of the world and are the targets of some of the most important commercial fisheries. They occur throughout the water column in high latitudes—from deep-sea benthic habitats (close to the bottom) to coastal waters—but are found mainly in the deeper depths of tropical seas.

In fact, gadiform fishes are among the most diverse group of fishes inhabiting deep waters, and in some areas they are the dominant species in terms of biomass, making them of great ecological importance. In other cases, such as the giant grenadier (Coryphaenoides pectoralis), they are at the top of the food chain and have few, if any, predators of their own.

Gadomus arcuatus (Family Bathygadidae) has a very long chin barbel for searching for food and long tactile rays in the pelvic and dorsal fins; these characters are often lost upon collection. This is a great example of how direct observations can provide new information on behavior and morphology, including live coloration. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, Exploring Puerto Rico’s Seamounts, Trenches, and Troughs.. Download larger version (jpg, 1.3 MB).

Despite their great commercial and ecological significance, and a long history of taxonomic study, our knowledge of the evolutionary relationships (systematic) and the taxonomy of these fishes is still unclear. Currently, researchers that study the diversity of fishes in this group recognize anywhere between 11 and 14 families, about 75 genera, and more than 500 species. Only two species are known to reside in freshwater habitats.

Some of the gadiform fishes we have seen during Océano Profundo 2015 are rattails or grenadiers, which belong to the Family Macrouridae. This family is the most diverse within the gadiforms, with almost 400 recognized species. They have a worldwide distribution and are found at great depths, from the Arctic to the Antarctic. Members of this family are among the most abundant deep-sea fishes. An important commercial fishery exists for the larger species, such as the round-nose grenadier (Coryphaenoides rupestris) and the rough-head or onion-eye grenadier (Macrourus berglax). Because these are long-lived species that reach maturity at a relatively old age and have very low reproduction rates, they are highly vulnerable to over-exploitation and have a low resilience to fishing.

Early research efforts in the area have included trawling (sampling with large nets), as well as a few dives with the Alvin and the Johnson-Sea-Link submersibles (both manned deep-ocean research submersibles). However, most of these earlier dives were in waters less than 1,000 meters.

With the Okeanos Explorer's dual-bodied remotely operated vehicle (ROV) system, Océano Profundo 2015 has provided the opportunity to capture high-quality and high-resolution imagery of gadiforms in deep waters, as the expedition focused on unexplored areas at depths mostly beyond 1,000 meters.

ROV Deep Discoverer has two high-definition underwater video cameras and the newest lighting technology, while Seirios has a camera suspended above the other ROV and serves to illuminate and image the surroundings. The technology used in these submersibles and the skilled pilots capture amazing videos and close ups of the fishes that help us to improve our understanding of deep-sea creatures in their natural habitat. These videos are opening a window into fish behavior (e.g., swimming, searching for food sources falling from above, etc.) and are providing information on morphological characteristics (e.g., coloration, length of chin barbels, fin filaments, etc.) usually lost due to damage to the fish when being abruptly pulled to the surface from trawling or after being stored in museums for tens to hundreds of years. Additionally, information of the different benthic surfaces and depths they inhabit is important.

We saw different species in different habitats (from muddy bottoms to rock walls) and depths (3,800-450 meters). For example, the rattail Coryphaenoides armatus occurred in some of the deepest areas explored, along rock walls at depths ranging from ~3,300-3,800 meters, whereas other species were found much shallower. For instance, the grenadier Gadomus arcuatus was imaged at 900 meters in a very complex, rocky habitat.

The resolution of some of the videos allows counting fin rays of some of the fishes (that was amazing!). These characters are key among others to identify rattail species. Thirteen rattails from at least two families were observed (Macrouridae and Bathygadidae), including Nezumia bairdii, Gadomus arcuatus, Hymenocephalus sp. and several species of Coryphaenoides. We are still working on the identification and conferring with other specialists in the group. Despite of the great advantages of recording these fishes, it is possible that some of the images will not be enough to identify them at species level, and future research cruises to collect samples will be needed.

Given the commercial and ecological importance of this group of fishes, it is important to clarify the taxonomy and the systematics of the group and further understand their habitat usage in deep waters. This basic knowledge provides needed understanding for efforts to conserve the biological diversity of gadiform fishes and to inform fisheries management.