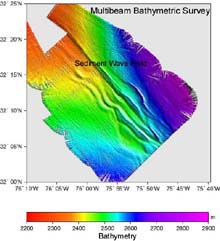

A high-resolution bathymetric map of the Blake Ridge. The map shows a sediment wave field with long ridges running from northwest to southeast. Such features may be important locations for gas escaping from the sea floor. Click image for larger view.

'We Have Biology!

September 25, 2001

Paula Keener-Chavis, Director

South Carolina Statewide Systemic Initiative's Charleston Math and Science Hub

Deep East Education Project Coordinator

The sea called ever to the dwellers on shore, and even those who might not answer its call felt the thrill and unrest and mystery and possibilities of it.

--L.M. Montgomery, Anne’s House of Dreams

As the Alvin deep submergence vehicle makes its first historical dive on the Blake Ridge, the weather is dreary and a thunderstorm approaches from the distance. Rain clouds are beginning to surround us, the air is balmy, and the gray seas are touched lightly with small, frothy whitecaps that become more numerous with each rolling wave. Everyone is busy with their own research tasks, preparing for Alvin's return to the research vehicle (R/V) Atlantis and the precious living samples that will be the first ever collected by a submersible on Blake Ridge. We anxiously await news from the depths below.

"We have biology!" shouts one of the graduate students as he hurriedly enters the ship’s

computer lab to spread the historic news. "Dr. Van Dover says there are lots of mussels, and possibly clams, and she also reports lots of juvenile specimens!" All who hear the news are excited, and the anticipation of the submersible’s arrival grows.

Alvinocaris shrimp (arrow), which have been found at the Florida Escarpment cold seep and at Mid-Atlantic Ridge hot vents, use large mussel shells for habitat. New mussels indicate that the Blake Ridge community is actively recruiting. Click image for larger view.

Several hours later, another report comes back from Alvin. "We have successfully collected three mussel-pot samples and are headed to look for bacterial mats." The pilot reports that they will begin the ascent to the surface within 30 min, and it will be several hrs before Alvin breaks the surface. A final science report from the submersible reports 3 mussel pots, 10 push-core samples, 1 rock, 1 slurp sample, and clams.

The Thrill of Exploration

As our chief scientist, Dr. Cindy Lee Van Dover, emerged from the Alvin at 5:15 pm, she was greeted by cheers and claps from her colleagues. She reported seeing "mussels a foot long with many juveniles, cake urchins galore, and hills of little clams." She continued, "It was just amazing. They are by far the biggest mussels I have ever seen." A scoop sample was taken where the small clams were located. At a depth of 2,155 m, the bottom was quite muddy, with areas of the ocean floor rising to about 5 m in height. No bacterial mats were observed.

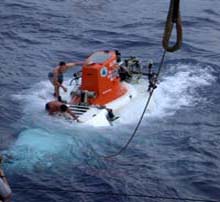

Alvin is recovered in rough seas. Standby boat picks up divers once the sub is hooked. Click image for larger view.

As we processed the samples in extremely cold water, organisms living among the mussels were gently rinsed off into 5-gal buckets. We then measured the displacement volume of the mussels, and sieved the remainder of the sample using sediment sieves. Large items, including brittle stars, a shrimp, shell fragments, polychaete worms, tiny sea cucumbers, clam shells, sipunculid worms, gastropod shells, and anemones were preserved separately from the fine mud samples. The mussels were then measured before being further analyzed by Dr. Van Dover's graduate students.

Undergraduate Mark Doerries was honored to take his first dive in the Alvin. As such, he was greeted with the traditional "first timer's ice-water bath" as he set foot back on deck. When asked how it felt to go about 1.5 mi down into the ocean depths, he was, at first, speechless. Finally, he said, "It was amazing to see what's down there. The colors -- purples, reds, pinks -- were stunning, and the mussels were enormous. We also saw lots of tiny clams."

Alvin collected this ft-long (27 cm) chemosynthetic mussel, Bathymodiolus, today on the Blake Ridge . Click image for larger view.

Samples Galore

Giant gravity cores, 15 ft long and 2 in wide, are currently being collected at 2,156 m depth. aAt this depth, it takes approximately 80 min to collect one of these giant gravity-core samples. Dr. Carolyn Ruppel is collecting them for Dr. Steve Macko at the University of Virginia, who will conduct isotopic and sulfate measurement studies on them. Two of Dr. Macko’s graduate students are aboard the Atlantis. Another colleague of Dr. Ruppel’s, from Georgia Tech, will examine the cores' microbiology and compare the findings to cores collected in extreme environments in the Gulf of Mexico.

Dr. Barun Sen Gupta and Dr. Paul Aharon are getting ready for their dive in the morning. Dr. Sen Gupta hopes to find bacterial mats on his dive tomorrow, and based on today’s discoveries on the deep-sea floor, he is confident he will see more giant mussels and clams. "I really like the idea of intensively sampling a smaller area in a previously unexplored environment like we are doing here" he says. Dr. Aharon says that he hopes to find geological indicators of hydrates and possible outgassing from these sites.

Everyone is quietly working on sample processing in the main science lab. The last of the mussel-pot samples is being processed, and the last giant core for the evening has just been deployed over the portside. The seas are calm, the air is still balmy, and the day has been a busy, productive, and historic one in deep-sea ocean exploration. It's a very nice evening out here on the ocean tonight.

(top)

Shana Rapoport inspects a mussel pot used to collect mussels on Blake Ridge.

Interview with Shana Rapoport

First-year Graduate Student

Biology Program

The College of William and Mary

Ocean Explorer Team: What are your responsibilities on the Deep East Expedition?

Shana Rapoport: I'm here to assist with the biodiversity work and am also conducting my own research looking at metal levels within the mussels. Our plans are to use the Alvin submersible to remove mussels from a mussel bed at the seep site and place them into a milk crate strapped on to its basket. Alvin will then place the milk crate a short distance away from the seep site. On the last dive, the relocated mussels will be collected and brought back for processing in the lab. I will be able to make comparisons between metal levels in the transplanted mussels and the mussels collected directly from the original site. We will continue this research by performing a transplant experiment, over a longer period of time, starting in December at a hydrothermal vent site located in the Eastern Pacific Rise.

Ocean Explorer Team: As a first-yr graduate student, what is your perspective of the expedition?

Shana Rapoport: After being out at sea looking for a new vent site on the Mid-Atlantic Ridge and not finding one, I learned first-hand how difficult exploration work can be. It's extremely exciting to hear radio reports from Alvin that we are discovering what may be previously unknown biological finds on the Blake Ridge.

Ocean Explorer Team: What and/or who influenced your decision to study ocean science?

Shana Rapoport: Being a Girl Scout gave me leadership skills and the confidence I needed to pursue an unconventional career. My troop was always outside, sailing, canoeing, and spending a lot of time on the water. Growing up, my parents always told me that I could pursue a career in marine science or any other field that I chose. They encouraged me to explore all of my options.

Ocean Explorer Team: What do you expect to find at the site?

Shana Rapoport: I hope we find mussels of the genus Bathymodiolus, the same genus of mussel found on the Eastern Pacific Rise. To date, little "metal work" has been done on these organisms, and to my knowledge, no work has been done on metal bioaccumulation in mussels from seeps. Finding the same genus here would open the door to many comparisons between mussels found at seep and vent sites.

Senior undergraduate Mark Doerries.

Senior Undergraduate Student

The College of William and Mary, working under Dr. Cindy Lee Van Dover

Ocean Explorer Team: What are your responsibilities on the Deep East Expedition?

Mark Doerries: My senior honors thesis is a diversity study at Logatchev, a hydrothermal vent site at the Mid-Atlantic Ridge. I didn't get to visit that site this summer on a research cruise because I participated in a "sea semester" through the Sea Education Association. I'm on this expedition to get first-hand experience diving in Alvin and collecting samples from a similar diversity project. I also will gain experience processing samples, and will contribute to a discovery paper that we plan to write about Blake Ridge. My main objective is to learn.

Ocean Explorer Team: As an undergraduate student, what is your perspective of the expedition?

Mark Doerries: I think it's very exciting, and I feel privileged to have the opportunity to explore a site that no one has seen before and where we aren't quite sure what we'll find. It’s great to be one of the first people to see a mussel bed and other fauna on the Blake Ridge, and to be part of an ocean expedition. It’s very beneficial, and incredible, to watch all of the scientists at work here.

Ocean Explorer Team: What and/or who influenced your decision to study ocean science?

Mark Doerries: In my junior year of high school, I took a marine biology course that was field-based. I got interested in wetland ecology, primarily saltwater marshes. In my sophomore year of college, I took Dr. Cindy Lee Van Dover's course in invertebrate zoology, and I loved it. I felt that I had learned an incredible amount, and I got very interested in her research. I remember that she gave a lecture early on in vent ecology, and then I got a position in her lab. I was very lucky to acquire that position. While working with graduate student Mary Turnipseed on her Florida Escarpment samples, I learned a lot about taxonomy.

Ocean Explorer Team: What do you hope to do when you receive your undergraduate degree?

Mark Doerries: I plan to go to graduate school. I'm seriously considering a research career in ocean science, but I may not limit my decisions solely to the field of ocean science.

Sign up for the Ocean Explorer E-mail Update List.