By William H. Thiesen, Ph.D.

Atlantic Area Historian, United States Coast Guard

Originally posted in The Long Blue Line

The Bear is more than just a famous ship; she is a symbol for all the service represents—for steadfastness, for courage, and for constant readiness to help men and vessels in distress.

—Captain Stephen Evans, The United States Coast Guard, 1790-1915

As the quote above indicates, United States Revenue Cutter Bear’s story reflects the U.S. Coast Guard’s core values. This extraordinary ship, on which legends were made, remains the most famous cutter in Coast Guard history.

Bear was designed to work in ice-bound conditions before the use of icebreakers. Built in 1874, Bear was designed specifically to work in ice-bound conditions. She was a 198-foot, 700-ton barkentine rigged steamer constructed in Scotland for sealing in northern waters. In 1874, iron proved too brittle for use in the cold Arctic, so Bear’s hull was built of wood, reinforced with six-inch thick oak planks and sheathed with Australian “ironwood” for a total hull thickness of ten inches. Bear also boasted a steel-plated bow; retractable screw and, in case of long periods underway, she had extra space for fuel, supplies or added passengers.

In 1881, Lt. Adolphus Greely, a member of the U.S. Army’s Signal Corps, led an expedition to study the weather and winter conditions on Ellesmere Island northwest of Greenland. Attempts to relieve Greely’s expedition in 1882 and 1883 proved unsuccessful and members of the expedition began to die of disease and starvation. In 1884, the U.S. Navy purchased Bear and, in June 1884, she helped rescue Greely and the five surviving members of his expedition.

In the spring of 1885, the Navy transferred Bear to the Revenue Cutter Service and, in early November, she began a voyage to California around Cape Horn. Captain Michael Healy took command of Bear in April 1886 after she arrived at her homeport of San Francisco. A veteran of Alaskan waters and skilled ice pilot, Healy was the first African American to receive a commission from the U.S. Government and the first to command a Federal ship. Under Healy, Bear served on the Bering Sea Patrol, which comprised between 15,000 and 20,000 miles of cruising. Conditions on Bering Sea, were harsh, dangerous, stressful and, at times, deadly. Healy described the pressures of serving on the Bering Sea assignment: “to stand for forty hours on the bridge of the Bear, wet, cold and hungry, hemmed in by impenetrable masses of fog, tortured by uncertainty, and the good ship plunging and contending with ice seas in an unknown ocean.”

As an Alaskan cutter, Bear saved lives at sea and preserved the lives of those struggling to survive in Alaska’s frozen frontier. The native people of Alaska had relied heavily on whaling and fishing when the territory came under U.S. control. However, after foreign whaling, fishing, and sealing vessels entered Alaskan waters, fish stocks began to diminish, causing large-scale malnutrition and starvation in native villages. To solve the problem, Healy convinced authorities that Siberian reindeer should be introduced to Alaska. Healy’s views won over government officials and, in 1892, he brought over the first shipment of reindeer to the Seward Peninsula and established a reindeer station at Port Clarence. By 1930, Alaska’s domesticated deer herds totaled 600,000 head and 13,000 native Alaskans relied on the herds for life’s essentials.

Under Healy, Bear’s humanitarian support of Alaska not only included better nutrition for native communities, she also protected endangered seal herds from poachers. Cutters patrolled the waters of the Pribilof Islands seizing poaching vessels of all nationalities. Bear enforced seal hunting regulations into the early 1900s and, in 1892, she was on hand when military action nearly erupted between the United States and Great Britain over seizure of British sealing vessels.

By 1896, Healy had served ten grueling years on the Bering Sea Patrol. During this time, Bear controlled illegal liquor distribution used to exploit native people in the territory. Native people called the Bear “Omiak puck pechuck tonika” or “the fire canoe with no whiskey.” Ironically, while one of Bear’s missions was to interdict the smuggling of illegal liquor to native Alaskans, the stress caused by a decade of cruising encouraged Healy’s own drinking problem. In 1896, the Service relieved him of command, dropped him to the bottom of the captain’s list, and placed him out of Service for four years. The Service later reinstated him and he commanded other cutters before retiring in 1903 as the third-most senior officer in the Revenue Cutter Service. Physically spent, he died a year later at the age of 65.

A year after Healy transferred off the Bear, eight whaling ships became trapped in pack ice near Point Barrow, Alaska. Concerned that the ships’ 265 crewmembers would starve to death, the whaling companies appealed to President William McKinley to send a relief expedition. For a second time in her history, Bear would support a major rescue mission into the Arctic. In late November 1897, soon after completing her annual Alaskan cruise, the Bear took on supplies and sailed north from Port Townsend, Washington. This would be the largest of several mass rescues of American whalers undertaken by Bear during the heyday of Arctic whaling. And, it was the first time before recent global warming that a ship deliberately sailed into Arctic waters during the harsh Alaskan winter.

To lead the so-called Overland Relief Expedition, Bear’s captain, Francis Tuttle, placed Lt. David Jarvis in charge of a team including Lt. Ellsworth Bertholf, Surgeon Samuel Call, and three enlisted men, and tasked them with driving a herd of the newly introduced reindeer to the whaling ships. Using sleds pulled by dogs and reindeer, the rescue party set out on snowshoes in mid-December 1897. In late March 1898, after over three months and 1,500 miles in ice and snow, the rescue party arrived at Point Barrow. The expedition delivered 382 reindeer to the starving whalers with no loss of human life. Jarvis later recounted the rigors of the expedition: “Though the mercury was -30 degrees, I was wet through with perspiration from the violence of the work. Our sleds were racked and broken, our dogs played out, and we ourselves scarcely able to move, when we finally reached the cape [at Pt. Barrow] . . . .” For their work, Congress awarded Bertholf, Call, and Jarvis a specially struck Gold Medal. Jarvis later assumed command of Bear, as did Bertholf, who rose through the ranks to become the first commandant of the modern Coast Guard.

Gold had been discovered in Canada’s Klondike in 1896 bringing with it hundreds of thousands of prospectors, miners, and their followers to the coastal towns of Alaska. The Klondike was followed by gold discoveries in Nome and then Fairbanks, Alaska. This rapid migration to the Alaskan gold fields continued for over 10 years and brought with it the need for law enforcement, medical services, and humanitarian relief. In the boomtowns of Nome and St. Michel, revenue cuttermen from the Bear and other cutters patrolled the streets, cared for the sick, and enforced the law where there had been none before. In addition, Bear evacuated hundreds of invalids, criminals, and sick and desperate miners from the gold fields back to Seattle, where they received proper care.

During the 1898 Spanish-American War, U.S. military leaders had harbored a fear that Spanish privateers would terrorize the West Coast. Consequently, they hatched a plan to defend the coast using revenue cutters stationed out of California and Washington. This plan included arming and armoring the Bear. But the war ended before Bear had a chance to complete the Overland Relief Expedition, so there was no need to fortify the cutter. During World War I, the United States remained neutral through much of the war and faced few threats in the Pacific theater after it entered the conflict. Consequently, the Bear continued her Bering Sea Patrols as she had before the war.

Bear also provided humanitarian relief to regions outside of Alaska. For example, the cutter was laid up in San Francisco when the 1906 Earthquake struck. In the quake’s aftermath, Bear’s men immediately set to work using the cutter’s steam launch to transport goods to the waterfront and worked with local authorities in search and rescue and law enforcement. During this effort, Bear personnel worked closely with U.S. Army units then under the overall command of General Adolphus Greely. After the relief effort, President Theodore Roosevelt personally thanked the Revenue Cutter Service for its “prompt, gallant and efficient work.”

By the mid-1920s, Bear had served Alaska for over 40 years and on over 30 Bering Sea Patrols. During that career, the whaling fleet had sailed out of the Arctic fogs into the mists of memory and waves of miners had come and gone. As Alaskan settlements developed, civilizing influences once provided from the sea by Bear became locally available on land. Life in Alaska had become more civilized as new technology shortened distances between Alaska and the lower 48 states. These improvements included modern aids to navigation and lighthouses, the telegraph, military bases, steel steamships, the submarine cable, reliable aircraft, and the radio. The venerable cutter had witnessed many changes in the north and, in 1927, President Calvin Coolidge officially signed Bear over to the City of Oakland to become a historic museum ship.

But the venerable Bear was destined for greater glory. After her retirement by the Coast Guard and her brief career as a floating museum, Arctic explorer Richard Byrd re-activated the famous cutter. In 1928, Byrd used Bear as one of two ships for his first Antarctic expedition in which he established the well-known research base at Little America. He returned home in 1930 and used Bear on a second expedition in 1933. Byrd’s expeditions were the first American scientific missions to the Antarctic and they resulted in advanced discoveries in weather, climate and geography. Meantime, Bear still relied on her 19th century sail rig and coal-fired steam engine. Describing his trusted ice-ship, Byrd claimed: ould lower [her] head and bore in. Therein lay the merit of the honorable and ancient Bear . . .”

In the late 1930s, President Franklin Roosevelt placed Rear Admiral Byrd in charge of the United States Antarctic Service. And, in 1939, Byrd employed Bear once again to reach his base in Antarctica. Prior to this cruise, to the Antarctic, technological change had overtaken Bear’s original design and construction. Her new diesel powerplant no longer required a tall coal-fired smoke stack and Bear’s barkentine rig was altered to support a scout plane. By 1941, with war clouds forming on the horizon, Bear evacuated the scientific personnel stationed at the Antarctic bases and returned to the States.

Bear not only served a variety of populations, she carried an ethnically and racially diverse crew. Like other Pacific-based cutters, Bear proved to be a cultural and ethnic “melting pot”—much more so than the nation she served. Bear carried a crew whose native lands not only included U.S. natives, but also Asian and Pacific Island nations, Europeans, and Scandinavians. And Bear held the distinction of carrying not only Michael Healy, the first African American to take a ship into the Arctic; she also carried George Gibbs, Jr., the first person of African descent to set foot on the Antarctic continent.

In 1944, at 70 years of age, Bear was reactivated by the Navy for service in Greenland, where she undertook her first mission as a United States ship in 1884. Bear served in the Greenland Patrol as USS Bear, only this time she looked very different from her first year in the Navy. In 1941, the Navy cut down her masts to support radio gear, added modern armament and equipped her to carry an amphibious reconnaissance aircraft. And unlike 1884, Bear relied on a Coast Guard crew during World War II. As a part of the Greenland Patrol, Bear cruised Greenland’s waters and, in October 1941, she brought home the German trawler Buskoe, the first enemy vessel captured by the U.S in World War II.

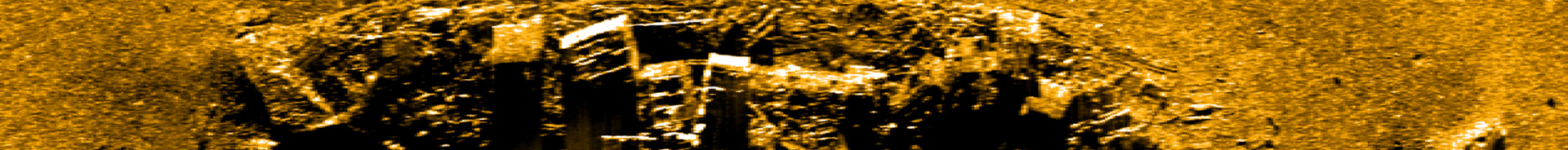

In May 1944, the Navy decommissioned Bear for the last time and transferred her to the U.S. Maritime Commission. Bear remained in surplus until 1948 even though her timbers were still sound. Buyers from Halifax purchased Bear hoping to use her in the sealing trade. She remained moored in Halifax for years until her Canadian owners finally sold her to a restaurant entrepreneur in Philadelphia. In March 1963, a seagoing tug took the old cutter in tow to her new home. During the transit, heavy seas developed and, at a point south of Halifax and 200 miles off the Massachusetts coast, Bear parted the tug’s towline. Bear began taking on water through her seams and the tug evacuated the crew trapped on board the powerless vessel. The historic ship began sinking and finally left the surface of the water at 9:10 a.m. on March 19th, 1963.

Over her long life, Bear explored, policed, protected, nurtured, defended, and helped preserve the polar regions of the world and the populations of humans and animals that inhabit Earth’s frozen regions. During that time, she performed the missions of search and rescue, ice operations, law enforcement, environmental protection, humanitarian relief, polar research and exploration, and maritime defense. And, she recorded many firsts, such as the first to ship to deliver reindeer to Alaska; first to journey into the Arctic in winter; first to chart parts of the Bering Sea; and first and only ship to serve under the U.S. Navy, Revenue Cutter Service, Coast Guard, and Antarctic Service. Cutter Bear and the men who sailed her remain a part of Arctic legend and the lore of the long blue line.