By William H. Thiesen, Historian, Coast Guard Atlantic Area

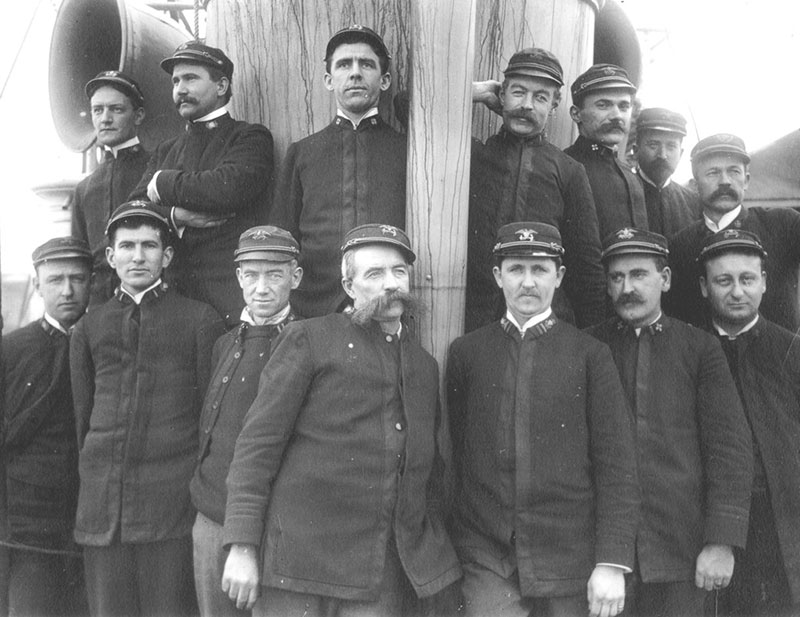

Bear officers, including Second Lt. Ellsworth Bertholf (front row far left), First Lt. David Jarvis (front row third from left), Captain Francis Tuttle (center), and U.S. Public Health Service Surgeon Samuel J. Call (back row far right). Image courtesy of the U.S. Coast Guard. Download larger version (jpg, 355 KB).

If you are subjected to miserable discomforts, or even if you suffer, it must be regarded as all right and simply a part of life; like sailors, you must never dwell too much on the dangers or sufferings, lest others question your courage.

–Lt. David Jarvis, U.S. Revenue Cutter Service, 1898

Revenue Cutter Service officer David Henry Jarvis wrote the above quote in his diary, journaling the Overland Relief Expedition, considered one of the most spectacular rescues in the history of the Arctic. As leader of the heroic expedition, Jarvis became one of the Service’s best-known officers to serve in the Alaskan maritime frontier.

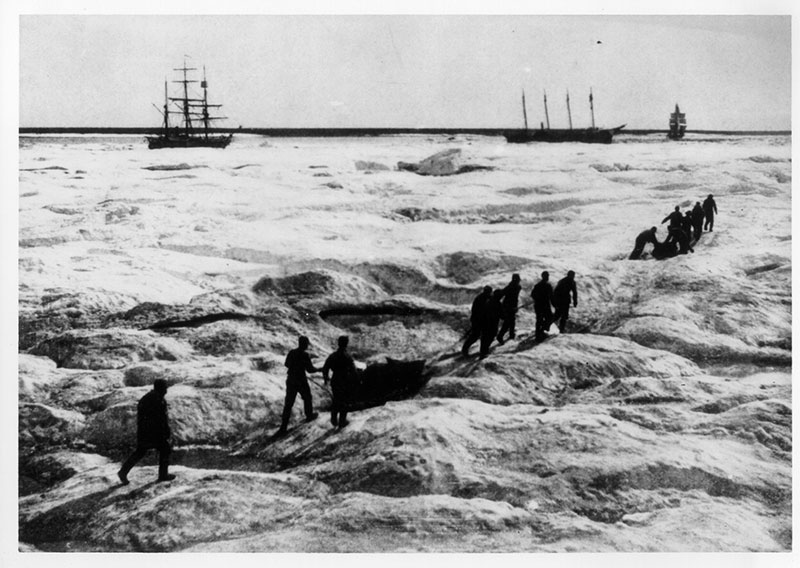

In 1897, eight whaling ships became trapped in pack ice near Point Barrow, Alaska. Concerned that the ships’ 265 crewmembers would starve to death, the whaling companies appealed to President William McKinley to send a relief expedition. In 1884, Bear had led the U.S. Navy’s famous Greeley Relief Expedition that saved some of the starving men of an Arctic scientific expedition led by Army lieutenant Adolphus Greeley. Now, under orders from President McKinley, Bear would lead a second major rescue mission into the Arctic.

1897 Overland Expedition approaches whalers trapped in the Arctic ice. Image courtesy of the U.S. Coast Guard. Download larger version (jpg, 1.0 MB).

In November 1897, soon after completing her annual Bering Sea Patrol, Bear took on supplies at Port Townsend, Washington, to return to the coast of Alaska. This would be the largest of several mass rescues of American whalers undertaken by Bear during the heyday of Arctic whaling. Moreover, it was the first time before modern icebreakers that a ship risked sailing above the Arctic Circle during the harsh Alaskan winter.

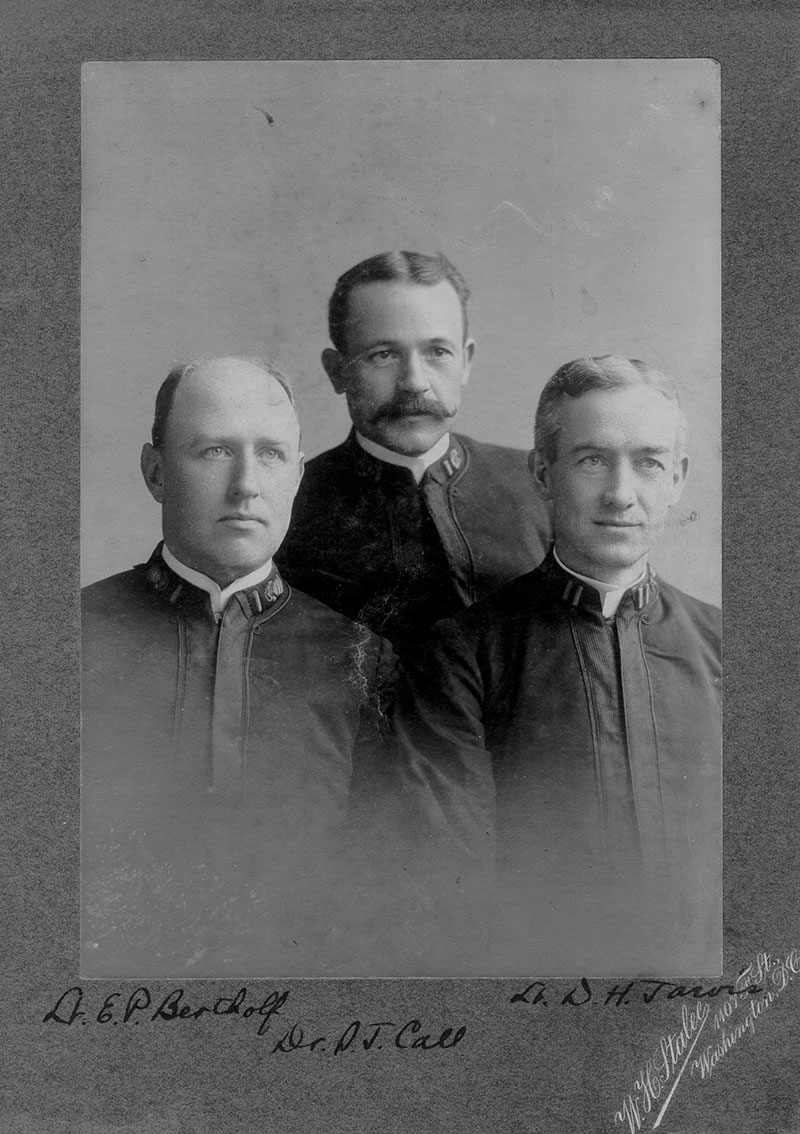

For this particularly dangerous journey, Bear’s captain, Francis Tuttle, took on only volunteer officers and men. To lead the so-called Overland Relief Expedition, Captain Tuttle placed executive officer Jarvis in charge of the rescue team that included Second Lieutenant Ellsworth Bertholf, U.S. Public Health Service Surgeon Samuel Call, and three enlisted men.

With no chance of pushing the wooden cutter through the thick ice to Point Barrow, Captain Tuttle put the party ashore at Cape Vancouver, Alaska. He tasked the men with driving to the whaling ships a herd of reindeer, newly introduced to Alaska. Using sleds pulled by dogs and the reindeer, the expedition set out on snowshoes on Thursday, December 16, 1897. So began a rescue effort unique in the annals of American history. It would require the relief party to cover 1,500 miles in the heart of the Alaskan winter over terrain alien to life-long mariners – snow, ice and tundra.

From left to right, Lt. Ellsworth Bertholf, Dr. Samuel J. Call, and Lt. David H. Jarvis posed for a commemorative photograph. Image courtesy of the U.S. Coast Guard. Download larger version (jpg, 1.2 MB).

On Tuesday, March 29, 1898, after 99 days of endless struggle against the elements, the relief party completed the journey. The expedition delivered 382 reindeer to the starving whalers with no loss of human life. In his expedition journal, Lt. Jarvis later recounted the final days of the Overland Expedition: “Though the mercury was -30 degrees, I was wet through with perspiration from the violence of the work. Our sleds were racked and broken, our dogs played out, and we ourselves scarcely able to move, when we finally reached the cape [at Pt. Barrow]...” When Jarvis and Dr. Call finally arrived at Barrow, Jarvis recounted that:

...when we greeted some of the officers of the wrecked vessels, whom we knew, they were stunned; it was some time before they could realize that we were flesh and blood. Some looked off to the south to see if there was not a ship in sight, and others wanted to know if we had come up in a balloon. Had we not been so well known, I think they would have doubted that we really did come in from the outside world.

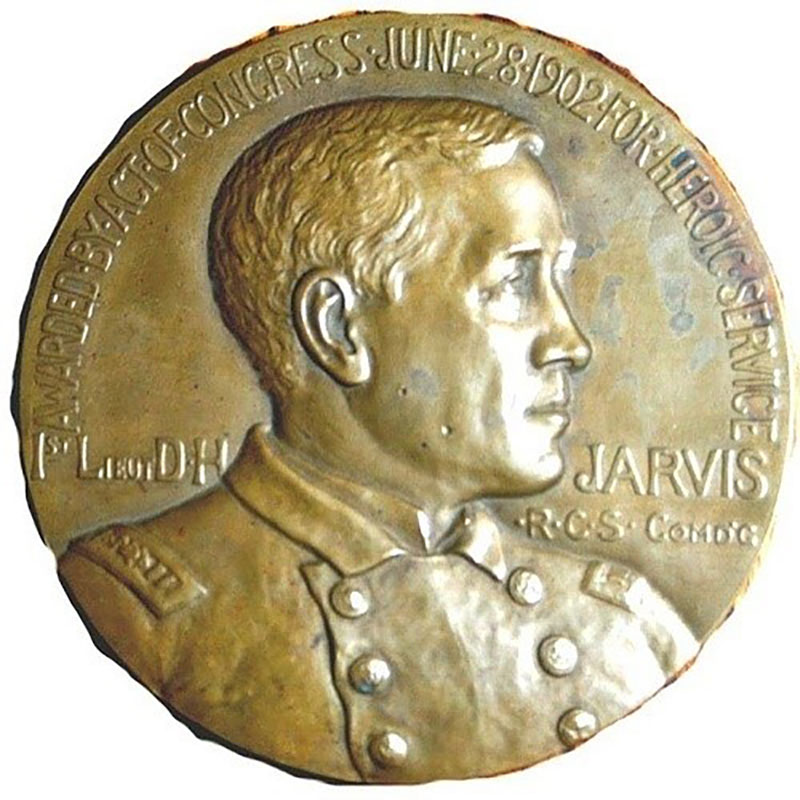

For their death-defying feat, President McKinley recommended Jarvis, Bertholf, and Call for a specially struck Congressional Gold Medal. In early 1899, in the aftermath of the expedition and the concurrent Spanish-American War, McKinley wrote in his recommendation letter to Congress: The year just closed has been fruitful of noble achievements in the field of war, and while I have commended to your consideration the names of heroes who have shed luster upon the American name in valorous contests and battles by land and sea, it is no less my pleasure to invite your attention to a victory of peace.

In recognition of his heroic deeds in the Overland Relief Expedition, Congress awarded Jarvis a Congressional Gold Medal referred to as “The Jarvis Medal.” Image courtesy of the U.S. Coast Guard. Download larger version (jpg, 203 KB).

After returning home from the expedition, Jarvis assumed command of Bear, as would Ellsworth Bertholf, who in 1915 rose through the ranks to become the first commandant of the modern Coast Guard. Another Bear officer, who volunteered for the cruise to save the whalers, Harry Hamlet, would also advance to the top post in the Coast Guard. Later, while still an officer, Jarvis became a special government agent at Nome, Alaska, and served there when a smallpox epidemic struck the community. In 1902, President Theodore Roosevelt assigned Jarvis as customs collector for the District of Alaska. In 1905, Jarvis was promoted to captain and, that same year, he retired from the Service after a nearly 25-year career. After Jarvis retired, President Theodore Roosevelt offered Jarvis the governorship of Alaska Territory, which he declined.

Captain David Jarvis died in 1911, six years after leaving the Revenue Cutter Service. He had become an important figure not only in the history of the Service, but also in the settlement of Alaska. A high-endurance Coast Guard cutter has borne his name, as does Mount Jarvis in Alaska’s Wrangell Mountains. Today, the Coast Guard awards the Captain David H. Jarvis Leadership Award every year to a Coast Guard officer who demonstrates outstanding leadership skills and inspires other men and women to strive for excellence. Jarvis’s memory lives on in the history and heritage of the U.S. Coast Guard and the State of Alaska.